Your cart is empty

If you happen to find yourself in Rosenberg, Texas, a timeworn town spilling southwest from Houston’s modern sprawl, I suggest a pit stop. On the corner of Third St. and Avenue I lies an unpretentious strip of stores. There, right smack dab in the center of them, rests a stockpile of unsung history – the Black Cowboy Museum. Beyond the front door of glass framed by electric blue panes lies a history long overdue for collective recognition. This history acknowledges the memory of a nascent West brimming in multiculturalism.

As a Black woman who spent more than my fair share of time living in Wyoming’s Western range, I’ve always been drawn to the richness and texture of the life that can be wrested from this un forgiving terrain. The land sculpts us to her will, not the other way around. How we stumble into the horn of plenty when we abandon the drive towards material possession. Although it’s easy to romanticize, few truly experience what it means to choose this path, forging a life of hard work and lonely solace in the open range. The reality of these modern times is that few get to directly live it – this is the sole preserve of the remaining cowboys.

Stories are life blood; they are what the West and humanity at large trade in. No matter your location in this vast nation, we all grew up fattened on the iconic myths, stories and histories of the Western range. It is part of our shared identity; our collective pride and shame. The Western imagination is rapturous and devouring, but what can you do when the prevailing myths and icons don’t bear any mention or resemblance to the likes of you? That is not to say I don’t enjoy how my Blackness sets me apart, but rather that at times I have questioned if this “West” is mine to claim – until I found Larry Callies and his museum.

When asked why he created the Black Cowboy Museum, Larry states, “God told me to.” Such a simple response veils the museum’s true impact. The museum is more than an act of faith; rather, it is a prayer made manifest, aimed at reclaiming history, ex tending recognition, and rectifying the absence of Black presence in the Western imagination. Decades ago, when Larry discovered that Black cowboys were not solely an anomaly of his family, but rather an abundant and rich pool of characters who participated in the events of what would eventually become the Western mythos, he drank this knowledge with the quickness of parched earth. After a prematurely snuffed music career, post-divorce, and with three grown children, Larry dedicated the remainder of his life savings to the purpose of quenching us all of our ignorance.

Suited up in his Wranglers and sponsor-riddled rodeo shirt, Larry is no different than any other cowboy casually spinning the yarns of his youth. He starts his tour of the museum with a framed collage that pays pictorial homage to his bright and all-too-brief country music career. Though cowboying is in his blood, Larry’s first dream was to follow in the steps of Charley Pride, a Black man who broke ground and rose to the Country Music Hall of Fame in the ’60s. Larry just about made it, too. With George Strait, known as the “King of Country,” as his manager, and having performed for George Bush Sr. and alongside the likes of Travis Tritt, Selena, and Emilio Navaira, it wasn’t long before Larry was offered an opportunity to record at MCA Records in Nashville. The dream went belly-up upon the discovery that his voice was deteriorat ing. A condition of vocal dysphonia caused a tightly strained, cracking pitch in his voice. Today, although he feels like invisible hands are clenching his neck, Larry remains steadfast in his desire to speak up.

Larry is a born entertainer and storyteller, two traits that con tribute to his magic as an absorbing historical guide. His charisma is made all the more apparent in his graceful detailing of the more morally reprehensible aspects of our American history – partic ularly as it pertains to Black and Native peoples. The relationship between a master and slave has scorched Larry’s family tree, and as such he has long acknowledged the more bleak and haunting roots of our American history. His entangled lineage equips him to hold the fuller spectrum of human nature, a tacit understand ing that nothing in our history is as simple as black and white. Larry does not shy away from complexity; Larry lives to color in the details.

Texas is the original seat of the American concept of the “cowboy,” a tradition greatly influenced by the Mestizo vaque ros of mixed Spanish, Latin and Indigenous ancestry – a live stock-raising heritage that preceded America and seeded present-day cowboy culture. Even more interesting is the fact that vaquero culture has roots tracing back to Moorish rule over Spain in the eighth century. Hailing from Africa, the Moors were Black Muslims whose wartime success over Spain is greatly attributed to their skilled horsemanship and breeding of hot-blooded horses. After roughly 800 years of rule, the Spanish reclaimed the Iberian Peninsula, but continued to cultivate the bloodlines begun by the Moors. Utilizing the advanced horseman skills of their former conquers, the Spanish shifted their gaze to the Americas. To this “new world,” they introduced horses that gave tribes like the Comanches their wartime edge; their cattle bloodlines would eventually give us the modern Texas Longhorn. These historical narratives remind us that no single event in time exists in isolation – and there is something beautiful in this recognition. The existence of Black cowboys, all cowboys for that matter, can be traced back to the exchange of information and tools between historic European and African empires.

In the early 1820s, when Texas was still claimed as part of Mexico, white settlers began migrating to the territory with Black slaves in tow. Though Mexico disapproved of slavery, enslaved Africans were present in the territory under both Spanish and Mexican rule. In 1825, slaves accounted for about 25 percent of the settler population, which amounted to an estimated 400 to 500 enslaved individuals. According to the 1860 census, that number would shoot up to 182,566 slaves. Despite the confusing mixture of conflict and a changing overlay of territorial ownership, this region ofTexas relied heavily on Black labor prior to its statehood in 1845, and long after slaves became freedmen on June 19, 1865. When one enters the Black Cowboy Museum, an enlarged black-and-white photograph immediately lassoes the gaze. In the image stands Henry Jones, the ancestral owner of one of the oldest white-owned settlements in Texas, the Jones Ranch. Behind Jones sit six Black men comfortably atop horses. Notably, one man has a brand in hand, indicating that these men were tending to cattle. The image is dated in the 1880s. One hundred and thirty years later, that same ranch would become the George Ranch Historical Park, where Larry worked giving tours and telling the stories of these Black cowboys.

The remarkable thing about this photo is how unremark able Black cowboys were in 1880s Texas. In pre-Civil War Texas, slaves were commonly found on horseback, riding the open range to gather up the abundance of unbranded wild longhorn cattle left over from abandoned Spanish settlements. The combination of dense, thorn-laden mesquite and chaparral thickets and the taxing Texas heat made cattle-gathering grinding work. Though ranchers also bred cattle, it’s estimated that five to six million Longhorns once grazed wild throughout the sparse ly populated Texas of the late 1860s. These conditions created a labor vacuum, which slaves and freedmen participated in filling.

Mike Searles, Professor Emeritus at Augusta State University and expert in the history of the “forgotten black cowboys,” points to recorded accounts from former cowboy slaves that reveal the higher degree of rapport that many of them had with their masters. Although these cowboys remained slaves, on horseback, far beyond the overseer’s gaze, they leaned into the sensory experience and temporary independence cattle gather ing yielded. In fact, these “cow hunters” typically endured less bondage, donned better clothing, and regularly ate meat. This was due to a combination of factors; cowboy slaves had a high degree of skill on horseback, meaning they had value to their masters, and also, according to Searles, “how you treat someone on horseback is different, because of how easy it would be for a slave to run away.” During the Civil War, when many white landowners took up arms for the Confederacy and headed east, it was slaves who maintained their ranches and cattle.

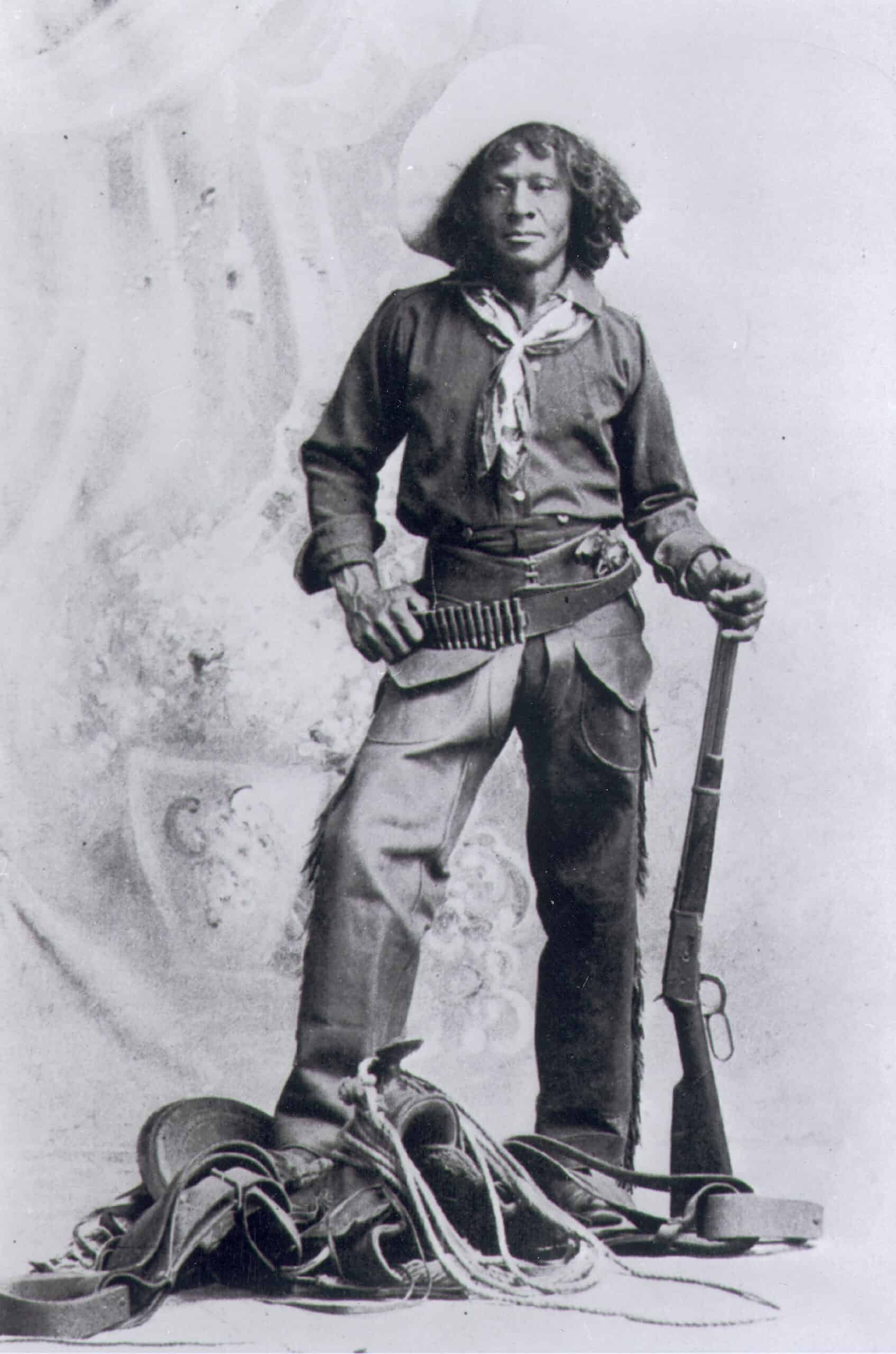

A confluence of factors allowed Black cowboys to persist post-enslavement. With the end of the Civil War in 1865, ranches were suddenly without the free labor they relied upon. This moment coincided with an increase in a national demand for beef, breathing fresh vigor into what became the height of the Texas cattle drives – a fountainhead of the Western cowboy myth. From 1866-1900, knowledgeable slave cowboys seamlessly transitioned into paid work as cowboys. Strikingly, it was not uncommon for paid cowboys to work for the same ranches under which they’d been formerly enslaved. It is estimated that between eight and nine thousand Black men worked as cowboys during this period. Though the number of Black cowboys was always greatest in the Texas Gulf Coast, their presence across the Western expanse was, by all accounts, about as noteworthy as a tumbleweed.

The very nature of frontier living breeds a quality of egalitarianism; the frontier and the edges of expansion rest most on skill and effort and least upon the color of one’s hands. That is not to say the frontier was in any way an ideal archetype for a diverse and equitable society, but confronted with the demands of survival, our ties to prejudice are less tightly bound. Yes, racism was omnipresent, especially in the attitudes, laws, and institutions that actively pursued Black disenfranchisement and exclusion, but as historian Kenneth Wiggins Porter states, “during the halcyon days of the cattle range, Blacks there frequently enjoyed greater opportunities for a dignified life than anywhere else in the United States.”

Much of the historical literature on Black cowboys describes recorded accounts affirming them as highly regarded cowmen. From riding to roping, gathering and branding, Black cowboys participated in all aspects of cattle management. Whether out of their own accord, implicit pressure or because they were asked, these men frequently took on the more dangerous and arduous tasks. Black cowboys were near the bottom of social hierarchies, and so they had to exercise great skill and doggedness to avoid being replaced. The records tell of how they swam the swollen rivers ahead of the cattle, took the first pitch out of rough horses, quelled raging stampedes, and even sang through the night to instill a sense of calm among their charges.

With such emphasis on talent, it’s unsurprising that more than a few achieved widespread acclaim for their accomplishments. Two commonly referenced Black cowboys are “Bulldogging” Bill Pickett and “Deadwood Dick” Nat Love; the mainstream popu larity of their respective stories is, however, the exception and not the rule. The novel Lonesome Dove entails the trials of a cattle drive and the deep bond between a white trail boss and a Black cowboy. This is not merely a fictional story, but rather under scores a lived history. Charles Goodnight, a trail boss from Tex as, did indeed travel for many years with a trusted black cowboy by the name of Bose Ikard. In one example of established faith, Goodnight ofren entrusted large sums of money to Ikard on the trail. When Goodnight learned of Ikard’s passing, he purchased a stone to adjoin his grave with a statement that read, “Bose Ikard served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior.”

Many Black cowboys have been immortalized in a litany of films, books, essays and art. & early as 1937, films like Harlem on the Prairie aimed to remind Americans that black people were present in the American West. Later, in the ’70sand into the ’90s, we had films like Buck and the Preacher, Buffalo Soldiers, and Posse. Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones’ book Negro Cowboys is one of the earliest texts to cover the extensive involvement of Blacks in the west. These works have tried, time and time again, to wake society to the fact that Black cowboys were as much a part of the West as their iconized white peers.

Still, they remain largely forgotten by mainstream culture. Larry’s museum is emblematic of our need to reflect and better understand how our past and present are inextricably linked, and how the confluence of the two dictate our future. Such a trove of American history raises the questions. Who gets to be iconic? Can our historical imagination ever be righted? Why did the story of the Black cowboy disappear?

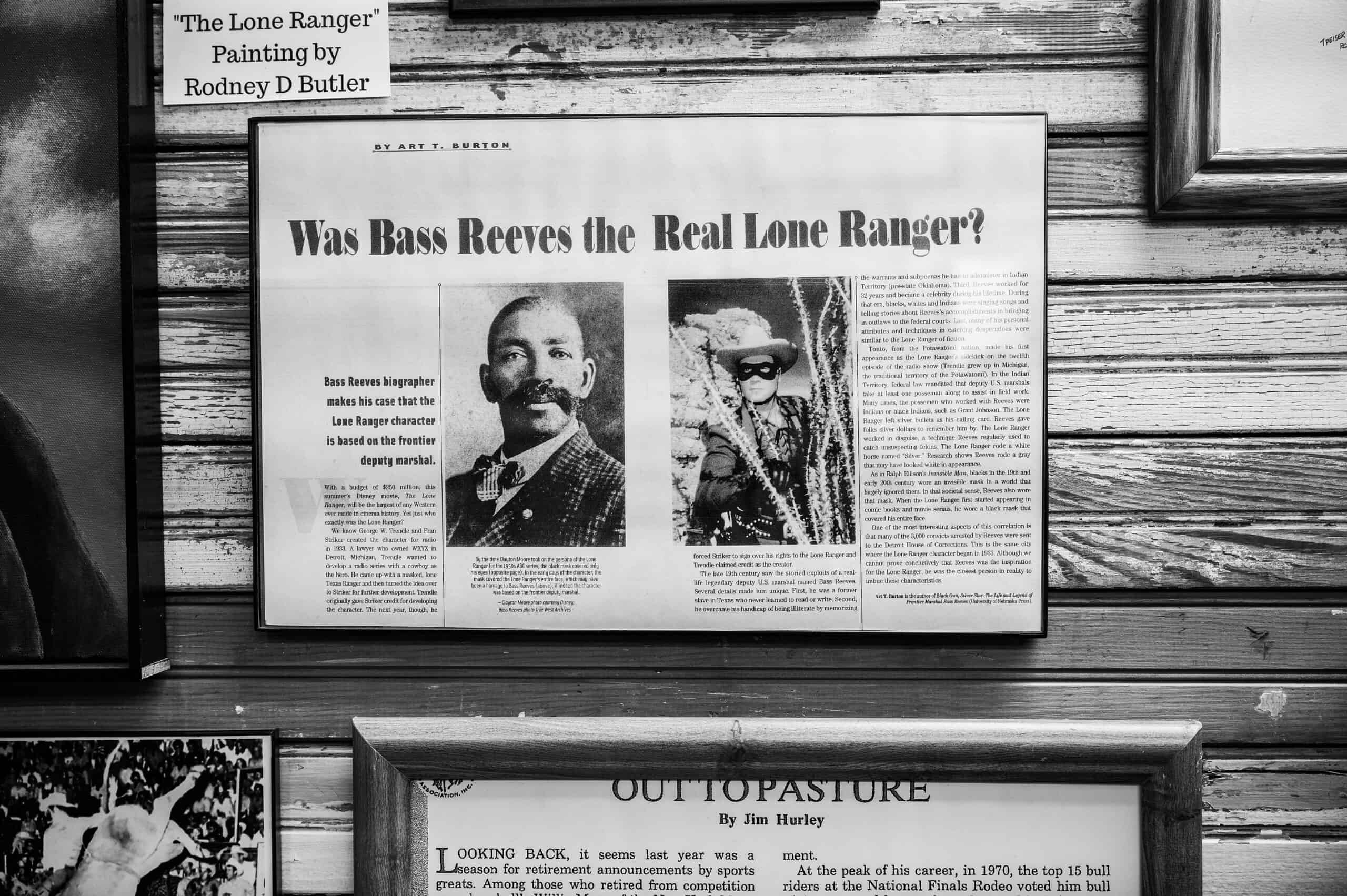

A few factors contributed to the omission of Black cowboys from the American imagination. First and foremost is a mixture of timing and exclusion. By the 1920s, when the sun began to rise for the fictionalized Western epics and character legends that we know today, the dust kicked up by the genuine events of the West had long since settled – the massive cattle drives of the 1880s were a distant memory. The writers who came to cover the exploits of an old West knew that literary grandeur was the only lucrative path, and America was living through a period where all her heroes were white. Racism did not allow for genuine interest in the sharing of Black men’s stories. & a consequence, the dime store comic books, followed later by the phenomenon of Western films, told the sto ries of white heroes in the West. At best, these narratives ignored the existence of Black cowboys, and at their most cutting, they replaced historical Black figures with fictionalized white heroes. What we are left with is a caricarure of the real West, whitewashed so that we can never know the full impact of America’s Black cow boys. As Black cowboy historian Philip Durham wrote, the non white cowboy was “confronted with a color line over which he could not ride.”

Another factor that contributed to the forgotten history of Black cowboys was the boom and consecutive bust of the cattle industry. The pinnacle era of the cattle kings and lucrative cattle drives began to decline in the 1880s due to overgrazin,gthe decreas ing profitability of beef, the railway system, and the onset of refrig eration. There were fewer and fewer cowboy posts to take up, and many of the Black cowboys lost out to their white counterparts. It was not uncommon for Black cowboys, picking up on the shifting times, to become Pullman porters on trains. Even Nat Love discusses this transition in his autobiography, from riding through the dust on horseback to the “iron horse and steel road.”

It is difficult to pierce the engrossing fantasy of the modern cowboy myth. The very heart of the cowboy appeal is sourced from the anonymity of real people and the ingloriousness of the labor. The sense of nobility surrounding this work is born out of the many nameless people who collectively shouldered what was considered undistinguished labor. During the height of the cattle drives, there was nothing glorious about being a cowboy; it was hard, tough work in which many men, no matter their color par took. That the labor was considered unremarkable in its time also contributed to the disappearance of the Black cowboy.

The Black Cowboy Museum and the artifacts housed in this three-room building in Rosenberg, Texas remind us that Black cowboys were not only part of the historic West, but are still an integral part of the landscape today.

In one moment, Larry shares with me how a painted image of him sitting atop his horse during a rodeo sold for a high number at auction, and has been printed over three thousand times. Then, Larry points to his family lineage, containing generations of Black cowboys. He mentions always being in the shadow of his father, Leon “Puggy” Callies, and his uncle, “Big Preacher” Williams, and how they taught him everything about cowboying and roping. They were true rodeo cowboys who competed in saddle bronc rid ing, calf roping, and steer dogging events at all-Black rodeos. His first cousin, Tex Williams, is a rodeo legend in his own right. Tex became the first Black man to win the Texas State High School Finals in 1967.

Larry’s stories don’t come close to ending there. First put atop a horse at three years old, Larry spent much of his childhood working and gentling cattle for rodeo. As an adult, he worked with his father for infamous Texas stock producer Sloan Williams, where he was responsible for a number of Texas Rodeo Hall of Fame bucking bulls. From raising cattle to working in rodeos and moonlighting as a saddle maker, he has just about done it all. His reels of personal stories call to mind a quote from arguably the most iconic Black cowboy, Nat Love, recounting his “love of showing off” and how it’s “a weakness of all cowboys more or less.” One thing is clear upon visiting the Black Cowboy Museum; the man does not stand apart from the museum. Larry is a cowboy in his own right.

One evening, after the heat of the day settled, we walked behind his home to greet his two high-withered horses, Tank and Swamper, who were grazing on the tall Texas grass. We saddled up and rode the quiet back roads through the neighboring ranches. He talked about how being a Black man in Texas has changed over the decades, and the many ways it hasn’t changed at all. He still sings despite his vocal dysphonia, putting music to poems he finds. Later, he picked up his guitar to play one for me, and even through the moments where the hearing gets rough, it is Larry’s unrelenting spirit to go on, to not be silenced that leaves the most profound signatures as he sings.

When it comes to the omission of Black cowboys from the Western story, you won’t find bitterness spitting from Larry’s lips. He possesses a graceful, albeit pained acceptance, that “that was just the way it was,” and yet he remains undeterred in his con viction that these histories must still be told. Herein lies the vital purpose of a museum such as Larry’s: history is passed down like a life-sustaining hardtack. Though unadorned and incomplete, this acts as a transference of knowledge in the multigenerational endeavor to combat legacies of erasure. If we as a society are able to fold a more complete picture of historical reality into our contemporary minds, then perhaps we can imagine a future befitting of our intertwined fortunes. Larry imparts his intent above the exit of the museum for all to read: “According to an African proverb, until the lion tells his side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

Related Stories

Latest Stories