Your cart is empty

STORY BY Katie Marchetti Hutton

PRESENTED BY DSC Foundation

Taking Aim” is a provocative Q&A with a diverse range of conservationists, scientists, professional hunters, rangers and advocates willing to share unique perspectives on controversial topics related to wildlife conservation in Africa. The intention is to provide an open forum for the authentic, uncensored voices of those on the ground and in the know. As their words reveal, there is no singular way to resolve the labyrinth of issues that enshroud the continent, yet we can still hope to remedy it together. That seems to be the largest hurdle itself, as collaboration between the hunting and non-hunting communities has remained elusive at best. We were disappointed to receive Dr. Mordecai Ogada’s refusal to be interviewed on the grounds that he “does not engage with any publications or organizations that are in any way connected to hunting.” As a carnivore ecologist, conservation leadership Professor at Colorado State University, author of The Big Conservation Lie and executive director of Conservation Solutions Afrika, we would have valued his insight. The voices included in this section represent excerpts from a larger conversation; our aim is that in reading their words and opinions, you will have a clearer view of the complexities of conservation in Africa.

THE GUESTS

Q1. What are the greatest challenges facing wildlife and conservation in Africa?

MICK – Stable political governance and political will — this will only be achieved when conservation and wildlife are seen as assets, not liabilities or luxuries. Habitat destruction and fragmentation — wildlife can be restored to an area, but if the habitat is destroyed, it is not possible. Alternative land use demands [such as] monocultures, human settlements, etc. Political relevance to governments — economic value/benefits. Corruption — the enemy within! Human population explosion. Poaching, especially that of a commercial nature. Sustainable financing — the threats posed by ideologies foreign to Africans, precluding sustainable utilization of natural resources, thereby devaluing them. Impacts of unrest and pandemics on tourism. Loss of sustainable utilization benefits.

ADAM – We have to find ways for habitat to be valuable and to support development, rather than becoming the victim of development, as it has in the UK and much of the rest of the developed world.

ANNETTE – Conservation in these areas not only faces challenges from within the governance of their own country, but often also from outside organizations, enforcing laws and regulations which may paint a bright picture theoretically, but are impractical, slowing down conservation processes rather than enhancing them. To protect and conserve wildlife and its habitat, it is important to understand how species interact within their ecosystems, and how they’re affected by environmental and human influences. Often, outside decision-makers have a limited understanding of complex natural systems and are too far detached from the realities to make responsible decisions regarding practicalities for conservation.

FLIPPIE – We face a lot of day-to-day challenges in protecting our animals. We have to make sure we get our animals through droughts with the constant change in the climate. In years where we have good grazing, we battle the risk of fire destroying all our grazing. The threat of poaching is something we need to be on the lookout for every day as well. In the long term, the biggest threat to wildlife in Africa is the growing human population taking land away from wildlife.

ANONYMOUS – In short, financial benefit from inside these reserves and parks usually goes a long way to protecting what is already there but rarely expands or helps outside the borders, and it is not likely to be a cross-benefit. All of this is much worse after the COVID-19 crisis, where any money that used to be shared is now just used to keep on the lights.

RAY – I’ve done quite a bit of work on the cultural value of certain species and the role these species play in communities. When you don’t have buy-in from all of those parties, conservation, protected areas and endangered species are under severe threat — introducing Roman law, introducing stricter penalties, is not influential and it won’t be influential. We’re seeing a lot of these species on many levels from birds right down to plants and to mammals, even marine species such as dugongs, being threatened because there aren’t conservation action plans in place. The problem facing Africa is that “conservation” is not a real term there. The terms such as endangered species, conservation, sustainability, don’t exist in Africa now.

FRANCOIS – Conservation belongs to the community, it belongs to Africans, it doesn’t belong to nature conservation or ecologists or conservationists, right? We are merely consultants, but the biggest challenge is that people feel that it’s not their problem. They’re not connected [and don’t realize] that this is their heritage. Their animals, their job.

SHANE – I think human expansion is one of the most extreme threats. We are an ever-growing population. Cities are getting bigger. Agricultural spaces are getting bigger and encroaching on unmodified lands. And I think this has certainly been one of the biggest factors when it comes to conservation issues.

Q2. Should the sustainable use of wildlife as a resource factor into future conservation efforts, whether that be protein intake by rural communities or an economic benefit to communities?

ADAM – One hundred percent yes. If habitat and wildlife are your primary resources, then you absolutely must be allowed to benefit from them. This might include non-extractive uses, like photo tourism, carbon credit schemes or land leasing, extractive uses such as hunting for meat, selling hunting opportunities for income, timber extraction, the use of plants and a wealth of other examples, or a mix of both. We all extract resources from the natural world, but many of us outsource and sanitize our extraction, often paying only lip service to sustainability. Sustainable use is perfectly possible though and, indeed, is occurring successfully in a great many places. We have to understand that communities live in many areas of conservation importance — if we attempt to exclude them from making use of their resources legally and sustainably (as they have often done for generations) then things rarely turn out well for people, habitat or wildlife.

FRANCOIS – People don’t value what they don’t even know about. They also don’t value what doesn’t contribute to them. But once you switch on that switch in their head, that it makes it a loss to them, the community becomes involved in rescuing animals, transporting animals to veterinarians, reporting cases of poaching, etc. Having the local community see value in these species — that does make a difference.

SHANE – I think when it comes to conservation issues, we have a tendency as Westerners and scientists to descend upon a place and try to dictate or explain or teach. What is really needed is a conversation about what sustainability means for specific places, for specific people and for specific ecosystems.

ADAM – Yes, this should be a factor. Species are usually very well adapted for the habitats in which they are found and can convert plant material into meat far more efficiently than cattle or goats can. Converting antelope habitat to “cattle habitat” often makes no sense at all.

ANNETTE – Yes, absolutely. Wildlife is an important renewable natural resource, and if sustainably managed, it can provide continuous nutrition and economic income, far more than what domestic stock can provide. Why is it so difficult to understand that humankind converted millions of hectares destroying the natural habitat to supply the human population with beef, goat and sheep meat? But when it comes to wildlife, do they not want to adopt the same policies and opinions? Keeping wildlife in its undisturbed habitat has far greater advantages than converting the piece of land for domestic stock. By maintaining an undisturbed habitat for wildlife, no eco chain is broken, no pesticides are used, the complete system is intact and income can be derived from many more facets, such as professional and specialized trophy hunting, tourism, live animal sales, meat production, breeding wildlife for other areas depleted of species — a far more effective and efficient foundation for the sustainability of the same area and its habitat resulting in species protection for sustainability rather than the destruction of all for only domestic stock farming.

ALEX – Wildlife has been an integral part of feeding people in Africa for millennia. Unfortunately, it has become unsustainable in many African countries as local communities are not allowed ownership of wildlife and would rather replace wildlife with cattle from which they can generate monetary value and deplete wildlife as a source of food without consideration of using game as a future food source. If local communities can generate income from the production of protein from the wildlife, they will have an incentive to sustainably utilize game so they have long-term income generation.

FLIPPIE – Wild animals have always been part of the food source for communities in Africa. The Lord put animals on earth for us to feed ourselves as we have done for thousands of years. Why should it change now?

Q3. How important is the phrase, “African solutions for African problems?” What do you take from it, and how has the influence of Western countries impacted conservation efforts in Africa?

MICK – This is absolutely relevant — each problem has its own unique set of parameters. An African “problem” is perceived differently by the African who is having his crop raided by elephants than the European who reads about it in a glossy magazine! Foreign-imposed solutions and policies are never going to have the local buy-in which is required for sustainability, whether one is an African conservationist or an Afghan politician! This is especially so considering an African’s perspective of the history of the Western world’s treatment of the environment. It would be wrong to broad-brush the influence of Western countries as positive or negative, as both good and bad consequences have played out. However, what the vast majority of Africans do find wrong is the undue influence that non-sustainable use and animal rightist ideologies have on African policies (eg. CITES Listings), while it is the Africans, not Westerners, who have to deal with the problems and be answerable to their peoples AND have to keep political and social support for conservation strong and alive. Tangible benefits are essential. The above said incentives and guidance are a different matter!

ADAM – You can still see a tremendous amount of “colonialism” in all its guises in the modern world, and nowhere is that more apparent than with regards to the continent of Africa. Just this week, we learned that the UK is one of the most nature-depleted nations on Earth, and yet we have the gall to preach to Botswana or to Namibia — nations with some of the best conservation records on Earth — how to manage their elephants or other wildlife. The problem is that many in the West still think they know best despite abundant evidence to the contrary. That is not to say there can’t be valuable insight or assistance, but dabbling in the policies of other nations rarely turns out well. There is a big difference between “support” and “control,” and that is something many Western organizations need to learn.

ALEX – Countries like Namibia have successfully shown how game numbers can be increased and conserved by allowing ownership and the sustainable uses of wildlife. In contrast, countries like Kenya, which do not allow hunting and where decision-making is largely affected by foreign NGOs, have lost 80% of their wildlife. People in Africa know the needs of African communities and how best to integrate wildlife conservation with the needs of the people.

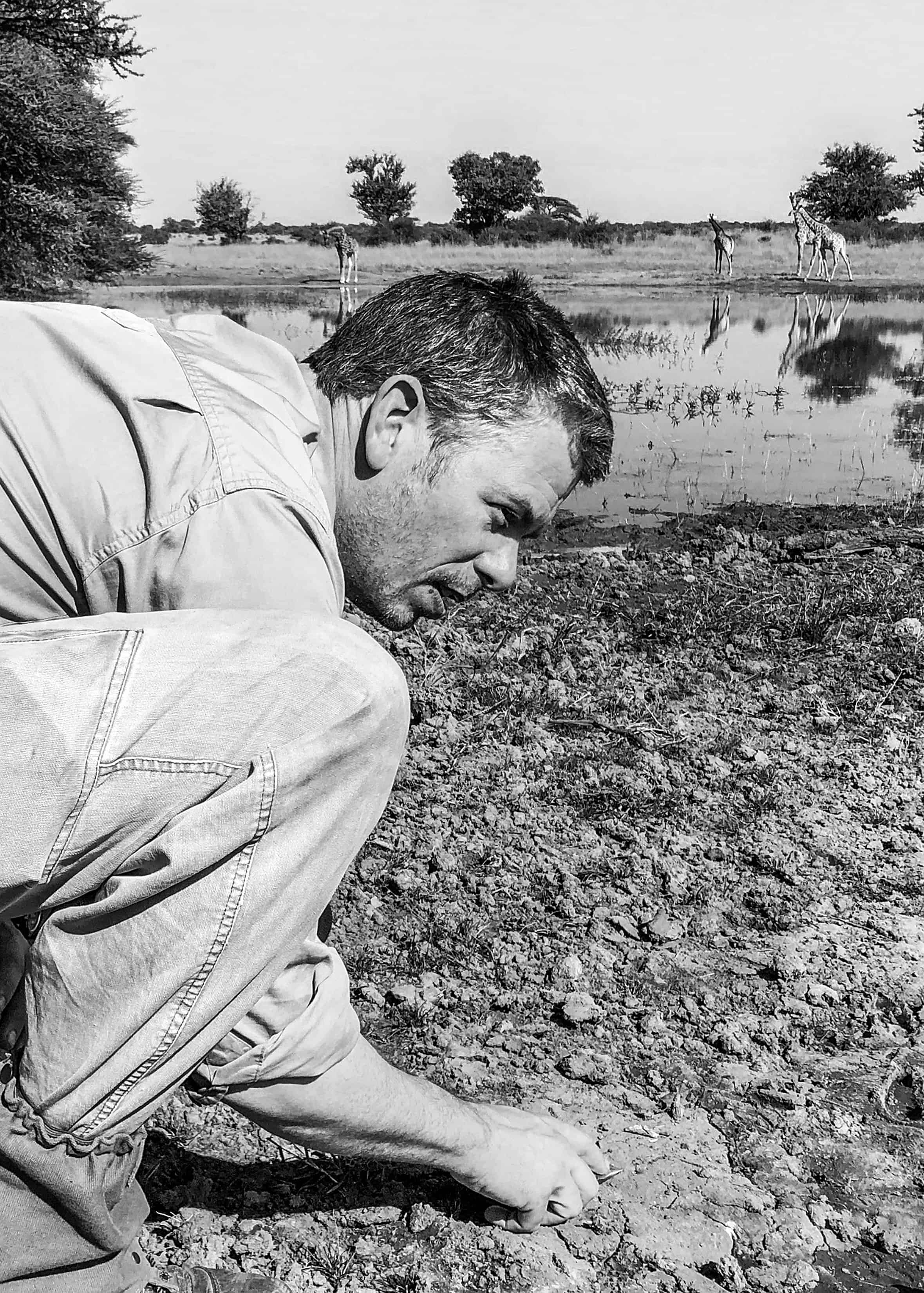

FLIPPIE – We were born with these animals, and we know how to live with them. We’ve lived with them for thousands of years, and where we use them and manage them sustainably, they still flourish. So many wild animals have been lost in Western countries. They should look at their own success in managing their game before they dictate how we should do it. We know our animals. When I drive out in the mornings, I can see which animals are rested and which have had a long night trying to stay away from predators. We know what they need and how to harvest them to make sure the herds stay healthy and breed well. How can anyone who was not born with these animals ever know as much about them as we do and then think they can tell us how to manage our animals?

ANONYMOUS – I think one must be eager for outside help as we cannot do it alone, and we do not have the resources. But many outside groups come in with their own agenda and ideas. We need help, but one must be willing to listen and understand the realities. Many big NGOs that some countries rely on have political agendas, which can harm good efforts. But we must also, as local groups, be less proud and learn from others as our ideas and ways are not enough. We are losing.

FRANCOIS – I’m not a big fan of the whole “animal activist approach.” And while I appreciate their emotion, I prefer the more scientific root of things and making my choices based on science. You have to talk to different cultures [to learn] their cultural perspective of [a given] animal because Westerners can’t expect other cultures to care the same because they’ve got a different view on that animal. And sometimes that view is food or a different way of utilization.

SHANE – I think it’s incredibly important. Every place, every ecosystem, every culture is unique, and it has its own unique history — evolutionary history, cultural history, etc. And I think it’s those things, those traditions, that have to be incorporated in sustainability efforts. We’ve seen time and again that indigenous means of modifying natural environments have a tendency to be more sustainable. Like in patterns of fire burning: when you burn, where you burn, how you burn, etc. I think a key to conservation is empowering those who are ultimately impacted by these efforts. Obviously, we want to preserve biodiversity for so many different reasons. But another goal alongside that is that we should be giving means and opportunity for the growth of populations that have lived alongside these ecosystems for so long.

Q4. Wildlife trade is often painted as negative and aligned with poaching and illegal trade. Does wildlife trade play a role in conservation efforts in Africa?

Q4. Wildlife trade is often painted as negative and aligned with poaching and illegal trade. Does wildlife trade play a role in conservation efforts in Africa?

MICK

There is a very obvious distinction between illegal and legal wildlife trade. Legal trade is subject to correct permitting of the entire process and official oversight of conformity to welfare and other required standards and regulations. Illegal wildlife trade is criminal by nature, has no oversight, and by its clandestine nature is entirely open to the shocking abuses that are so commonly associated (incorrectly) to all trade. For example, had legal trade not been possible, Eswatini would not have been able to re-introduce 22 species of locally extinct mammals from abroad, and her protected areas would be hard-pressed to justify their existence in the face of steep alternative land-use demands, not to mention the benefits of tourism.

ADAM

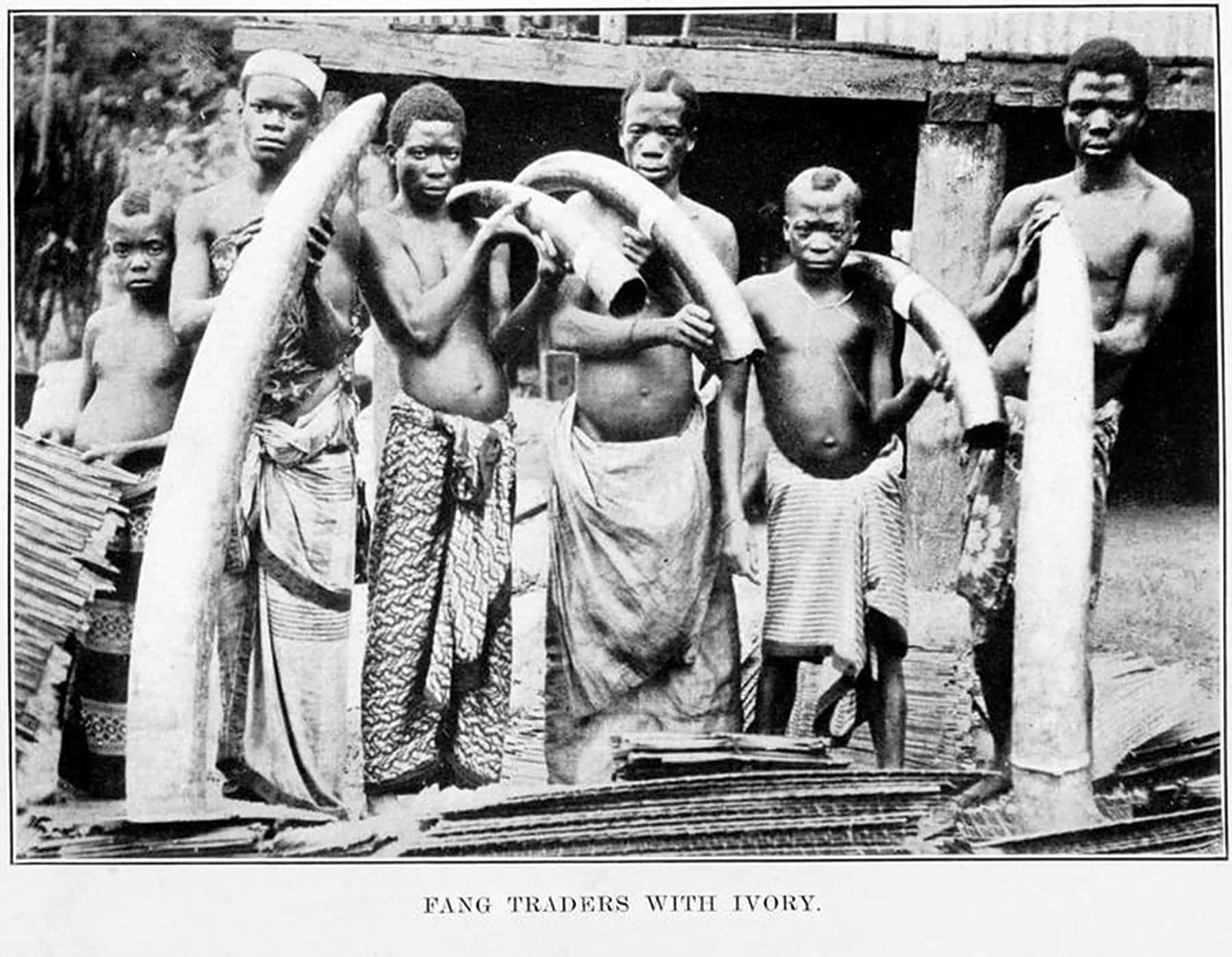

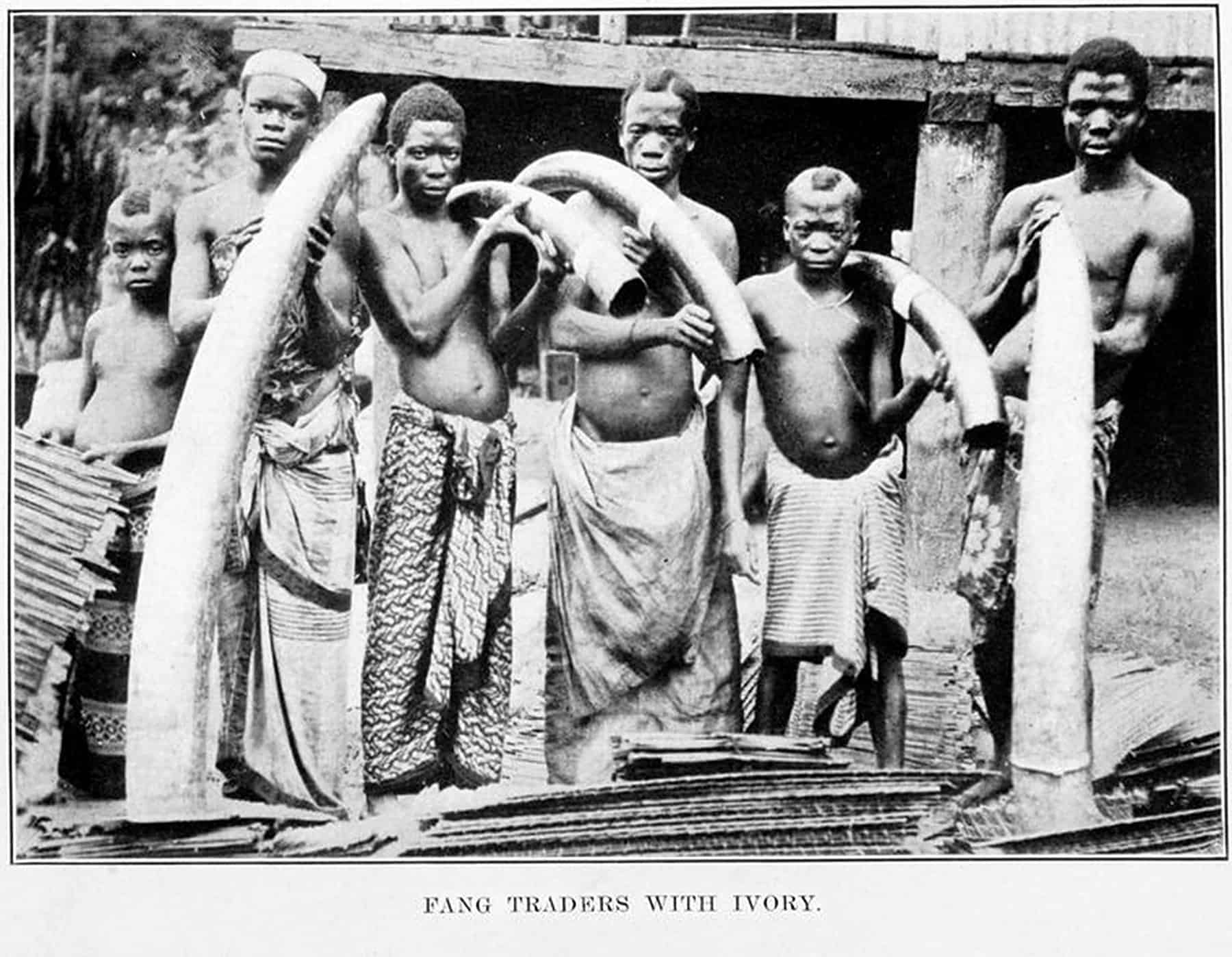

Wildlife trade is a thorny subject partly because so often when people say “wildlife trade,” they really mean “illegal wildlife trade.” IWT is a huge problem — whether it is pangolin scales, live exports of birds and reptiles, rhino horn, ivory or bushmeat. We should also remember that timber and plants are extracted and traded illegally. These can be, and often are, hugely damaging. However, the legal, regulated trade of products that are sustainably and ethically sourced can provide a real incentive for the conservation of those species and their habitat by providing meaningful and vital income. It is complicated, though, and each species, or even populations of that species, may require a different approach.

NATHAN

Particularly in the cause to save the rhino, we should consider every possible revenue stream. I think that legalizing illicit trade is not likely to have a net positive benefit and may unintentionally lead to empowering and emboldening syndicates, but any adaptation that gives wildlife value is to be strongly considered.

FLIPPIE

Looking after animals is just like having a garden — you need to harvest and take out weeds to make sure your plants are healthy. Just the same way, we need to manage the number of animals we have in areas so they are not overstocked [and do not] damage the habitat for other species. We can manage them by trade. Trade gives animals value and makes people want to look after them. If the animals didn’t have value, people would just use them as a source of meat until they are all gone. Trade is very important in conserving Africa’s wildlife.

RAY

We’ve seen firsthand what happened in Botswana when they put a moratorium on trophy hunting, such as elephant hunting, and opened up reserves to trophy hunting. People stopped coming to Botswana, and it destroyed those game ranches. All laborers were dismissed, they sold the game farms, those game farms reverted back to cattle ranching and goat ranching and crops. That’s the knock down effect. That’s the real effect.

especially with the women leaders of communities. But this is very difficult, and those running the parks have to understand that communities have very different priorities. Economically and socially, you have two or more very different sets of understanding and principles.

Q5. How important is local community integration in large-scale conservation initiatives? Can the successful conservation of species and ecosystems be achieved by a series of protected parks across the continent?

ADAM – The model of protected areas, in the form of national parks from which people are generally excluded, can work well. But often it doesn’t. The so-called “fortress conservation” approach runs a serious risk of ignoring the needs and basic human rights of communities, and there are well-documented cases where the approach has resulted in atrocities. People are not “trespassing in the wilderness” — they live there and have done so for a long time. That means that conservation without community involvement is a big problem for people and, ultimately, for conservation.

ANNETTE – For extremely threatened species, such as the gorillas, parks are of utmost importance, and they should be protected by an international and global protection force — not only by the country itself. Successful conservation of species and ecosystems can be achieved by parks across the continent depending on good governance. If managed properly, these parks provide the foundation of core conservation areas [and] untouched ecosystems, and set the examples for the community-involved conservation areas to strive for. At the same time, it is of utmos t importance that there be local community integration in new conservation initiatives to strive for permanent solutions to conservation. Projects based on the hopes for continuous overseas grants, without community involvement, are not sustainable and do not lead to permanent solutions.

ALEX – If we only want to preserve a few animals of each species, we can keep them in a few parks and make sure they survive. If we want to grow habitat and numbers, there is no way it can be done without integration with local communities, and this is the only large-scale option available in Africa. If local communities can benefit from the conservation of wildlife, it gives them a reason to want to share their land with wildlife.

FLIPPIE – It is important to integrate local communities with wildlife management to increase the land available for the animals, but it is hard for communities to be integrated safely with a dangerous game, so it will be easier to limit the dangerous game to parks. If people can make money from wildlife, then they will be more willing to live with them and look after them. My father used to make fires at night around the wells they dug for their cattle, and when elephants would come they would chase them away with fire. The elephants would want to drink at the wells and then trample the wells. Resources should be allocated for communities and animals to avoid conflict as much as possible. This will make communities more tolerant of sharing their land with wildlife.

ANONYMOUS – Community investment is a must. If a community does not buy in, then you work against yourself. Trust must be built — especially with the women leaders of communities. But this is very difficult, and those running the parks have to understand that communities have very different priorities. Economically and socially, you have two or more very different sets of understanding and principles.

Q6. Can wildlife and habitat survive the rapid human expansion across much of Africa?

ADAM – Yes it can, but whether it will remains to be seen. Central to this will be finding ways that habitat and wildlife can support development rather than become a victim of it.

FLIPPIE – We need to find ways to live together with animals. If people can’t make money from the animals, they have no reason to want to share the land with them, and animals will be pushed into parks.

FRANCOIS – Yes, the optimist in me wants to say yes. But one thing we have to realize is that we can’t plan on humans being separate from the wildlife system and from the nature system. Humans aren’t going anywhere. I always tell people, conservation is a ball rolling down a hill. The ball is never going up the hill, but what you can do is be behind the ball and tap it left and right. You can control what direction it’s going in, but pushing it back up is not going to work. So instead of thinking, how can we separate humans and natural areas? You can think of how you can integrate human life and wildlife.

SHANE – Yes. One of the things that my research has shown me is all these surprising and innovative and interesting and weird ways that life has adapted — by way of evolution — alongside us. It’s also clear that there are many species that are being driven very quickly toward extinction. So as an evolutionary biologist, when I think about questions like, “will life survive the age of humans?” Yes. I can say with a decent level of confidence that life, generally speaking, survives the age of humans in much the same way that it survives the five major extinctions of Earth’s past.

I think the big question is, are we going to survive us?

Q7. How can the interests and needs of humans and wildlife be met in the face of increasing human/wildlife conflict?

ADAM – The simple answer is by listening to and supporting nations to find the balance. We need to listen to communities, local knowledge and science. We need to stop taking simplistic Western approaches based on limited understanding and instead help in exploring new ways. I believe we are right to think of African wildlife as our international heritage, but that doesn’t give us the right to dictate conservation policies from the saddles of our high horses, thousands of miles away in countries that are woefully depleted of nature.

ANNETTE – A respect for ancient cultures to find the original intrinsic value of nature and its wildlife should be used as the foundation to build a sustainable conservation model where wildlife earns its value and provides a benefit for the community as wildlife stewards.

SHANE – A big part of that conflict comes from habitat encroachment. We are moving out and clearing more and more land every second of every day. So I think trying to understand the basic biology of species — how they move, what they need — and how to build sustainable, profitable agricultural systems in the light of that knowledge so that both can co-exist would be the goal. And maybe that is wildlife corridors. I think the dynamics will depend on where you are and what species you’re talking about, but I think building the needs of the natural world into economic business practices has to be paramount.

RAY – Human-wildlife conflict can be resolved if we bring in some sort of value that those people see toward wild animals. And here again: ecotourism operations, game, ranch, operation and sustainable use, I think this is part of the solution.

I don’t think it’s the solution for all problem animals — like India’s leopard population that’s causing havoc in some of the cities. And that’s quite scary because they’ve really adapted well to urban environments. I think those are going to be a problem. In South Africa, we’ve got a huge problem in Cape Town with wild baboons inhabiting urban areas, and baboons are quite a large, dangerous animal. They’re quite territorial. But humans have invaded there. Baboons have been here for thousands, if not many thousands, of years, and urban sprawl has sort of crept in upon their habitat. So we have to find a compromise, but it’s a very difficult topic and it actually requires workshops instead of just discussions.

Q8. How has the negative view of “trophy hunting” in Africa affected conservation efforts across the continent?

MICK – While the negative views of trophy hunting in Africa would appear to have dampened some peoples’ appetite for hunting, tourism has increased substantially (COVID aside), and it can be argued that photographic tourism is an adequate substitute for hunting. However, with the expenses and management pressures on wild places, and the need for the benefits to be shared among an exponentially growing stakeholder base, there is a dire need for both tourism and hunting to maximize the potential benefits derived from conservation areas — especially where some areas are more suitable to hunting than tourism and vice-versa. It is therefore senseless to adopt an either/or approach where there is clearly space and need for both. Unfortunately, the trophy hunting fraternity is very often its own worst enemy, having allowed unethical practices such as canned killing (not hunting!) to be tolerated or condoned — albeit often at arm’s length — especially in South Africa. The brash behavior of many hunters also brings no favors to the industry, especially given the fast-changing sensitivities of today’s world. There is a need for stronger self-imposed regulation among hunting associations if hunting is going to continue to have its rightful place and function as a contributor to the conservation of species [and] their habitats, and be of benefit to stakeholders.

ADAM – It resulted in a temporary, unpopular and ultimately hugely unsuccessful ban in Botswana that harmed communities and increased poaching. The ban on importing lion trophies in the US seems to have resulted in the abandonment of hunting concessions in Tanzania, which are no longer protected from unsustainable wildlife extraction and conversion to agriculture. Overall, it makes hunting more difficult, and that will have negative effects on habitat, wildlife and communities.

NATHAN – I encourage an ongoing conversation between hunters and those responsible for the protection of national parks and wild places, as well as between all of those with an interest in wildlife protection. We simply can’t afford antagonization between members of the conservation community. Politics is as likely to kill the rhino as poaching syndicates. The hunting community and industry can help bridge the international gap of education and conservation.

FLIPPIE – f there is no trophy hunting, there will be fewer animals. A farmer keeps his stock, not only to look at, but to eat and harvest. The same goes for wildlife: it is to be used for its own benefit and conservation because the farmer relies on it for his own survival. People want to tell us how to use our wildlife just because they have a different opinion about hunting animals, but they have no idea how to manage those animals and keep them alive.

Q9. How can the international community best support conservation efforts in Africa?

ADAM – By supporting, not dictating. By listening, not telling. And by making some attempt to understand the bigger, more complex picture. But overall, the best thing to do would be to understand the role of people, of communities. Our view of the great African wilderness, devoid of people, is wrong and harmful to understanding and supporting conversation.

ANNETTE – Conservation takes many facets to strive for a sustainable model. It is long-term; it takes unselfish and completely dedicated management directing funds to and for the better of conservation. It takes many facets to generate income, and by way of diversification, to pay for conservation such as tourism, hunting, breeding, wildlife capture and meat production. If funds are channeled back into conservation, all facets generating capital for conservation are important. Anyone traveling to Africa, either as a tourist or a hunter, contributes immensely to the conservation model if choosing their safari companies correctly.

ANONYMOUS – We must shine a light on corruption, and it will only come from international bodies to do this. In Africa, we cannot police ourselves well. Corruption is a way of life in many places, and self-interest means that those in power over animals care more for their jobs than they do for keeping animals safe. Just because you work in a park doesn’t mean you actually care about the animals. There needs to be exposure to this and pressure to do what is right. There is not much reason for hope sometimes, but groups like Eco-Defense are here doing something new, so maybe we have a shot at it.

SHANE – In terms of conservation efforts, there has to be a broad conversation. I think there has to be a conversation that includes basic biologists, like myself, evolutionary biologists, applied biologists, people in conservation, and also policymakers and city planners. It can’t be looked at as separate parts. It’s an integrative whole. And until we start thinking about it as an integrated whole, I think we’re going to run into a lot of problems.

There are success stories if you look at urban greening initiatives. Look at what they did in Singapore: a lot of that native diversity has rebounded because they drastically rethought what a city should be. And I think keeping that in mind — that people love being around green spaces — and building that in a way that’s conducive for wildlife, it makes a beautiful space and it gives people pride.

Q10. What do you want readers in the West to know or understand?

MICK – The complexity of conservation issues in Africa is difficult to grasp, and Africans will naturally be the best architects of the solutions. Agenda-driven foreign policies will always be subjected to pushback and will never arrive at lasting solutions. Remove the tangible benefits that establish wildlife and wild places as assets to the African economies and it will be doomed. The converse also applies!

ADAM – That things are far more complex than they imagine. That conservation is not about “hero” celebrities in 4X4s bottle-feeding giraffes, and it is most certainly not about depicting people that live alongside the wildlife as the villains.

FLIPPIE – We invite Westerners to come and see how we live. We have lived with wild animals for a long time; [Westerners] should not dictate to us how to manage our animals. They should learn from us and how we understand nature.

FRANCOIS – Conservation is a society mindset, and it’s a society’s job, not the conservationist’s job, to correct it.

RAY – The average wage in Central and West Africa is one dollar a day. These are very real problems. Hunger is a real problem. I think creating wealth, creating job opportunities by using ecosystems, can work. People from all over the world want to see these places and to see people in cultural dress. There’s not a shortage of people who want to come and visit them, but we need to make those places safe and not dangerous to visit.

Originally published in Modern Huntsman Volume 8

Related Stories

Latest Stories