Your cart is empty

STORY BY Tyler Sharp

PRESENTED BY Cabela Family Foundation

Dinner with Destiny

Standing on a cliffside path at the Four Seasons in Lanai, Hawaii, I downed what remained of my reposado on the rocks and prepared to walk into the dinner party. I was an outsider in a large but close-knit group that had not seen each other in two years — over 200 movers, shakers and change-makers in the outdoor world. I had been invited to be one of several speakers on a conservation panel about the future of hunting, but knew only a few people. As I scanned the verdant lawn for my table assignment, I couldn’t tell if it was the thick smoke from the Hawaiian torches or the two tequilas that blurred my eyes. Maybe it was both.

Finding my table, I noticed an elegantly dressed older woman standing with an empty glass of champagne and a look of confusion on her face. She reminded me of my very proper Texan grandmother, Mimi. I introduced myself, and asked her name and if she needed help finding someone. “My name is Mary,” she said as she gently shook my hand, “and I don’t know where the restroom is.” Having overheard that it was in a trailer behind the bar, I offered to escort her down the dimly lit path that wound through the exotically fragranced plants and trees that make these islands so special. I waited until she returned, walked her back, got her a fresh glass of champagne and took a seat at the opposite end of the table from her.

Given that I’m basically a glorified paper-pusher, I had a copy of Modern Huntsman with me, and the gentleman to my left asked to see it. His name was Dan, and he had a booming laugh, a dry, sarcastic wit, and a sharp mind. After flipping briskly but determinedly through the 256 pages, he asked me a series of pointed questions about the larger mission of Modern Huntsman. Seeing that he was a no-nonsense sort of person, I answered with minimal fluff. “Sounds like we’ve got a lot in common,” Dan said. “There are a few projects we’ve got coming up for our foundation that I think we could work on together.” Always open to collaboration with those of like mind, I asked him what the name of his foundation was. Dan reached for his drink, took a sip and, without even making eye contact, casually said, “The Cabela Family Foundation.”

I sat up straighter in my chair and tried to play it cool as the reality of the situation set in. Definitely glad I didn’t order a third tequila, I thought to myself. This was Dan Cabela, and I had escorted none other than Mary Cabela — the matriarch of the hunting industry — to the restroom, and I was now sitting at the dinner table with her family, or at least a small part of it. What followed was one of the most memorable dinners of my life, filled with great conversation, hearty laughter and, as it would turn out, a few more tequilas. With my bare feet in the grass and the tablecloth glowing with a mix of flickering torches and Hawaiian moonlight, I learned about the road ahead for the Cabela Family Foundation and where Dan (the Executive Director) wanted to see it go, and silently hoped that we could play a part in bringing it to reality. As always, time would tell.

Some weeks after the hangover in hawaii, and with the aid of a Texas congresswoman who got my passport renewed on short notice, I found myself standing on the edge of a dusty airstrip in Mozambique with mosquitoes buzzing excitedly around my head, reminding me that I had quit taking malaria pills over a decade ago. I was in an area called Coutada 11 — a hunting concession on the central coast of Mozambique that spans over 1,200 square miles and half a million acres. During their Civil War from 1977-1992, wildlife populations were decimated, largely due to meat poaching, yet the habitat remained intact.

Enter Mark Haldane, our host and the operator of Zambeze Delta Safaris, the outfitter responsible for taking charge of this concession and in the ’90s. Through relentless habitat improvements, conservation and anti-poaching work, Mark and his team have effectively brought the wildlife back from the brink of extirpation to an estimated increase of over 3,000% from when they took over. Game numbers can sometimes be difficult to pin down, but Mark, his son Dustin and his colleague Pete are all highly experienced helicopter pilots. They routinely perform aerial game counts, anti-poaching patrols and darting/ collaring missions, not just for themselves, but also for neighboring concessions, national parks, and other conservation groups. Through frequent aerial surveys, it has been determined that Coutada 11 has the highest density of non-migratory animals on the entire planet, and the highest density of a handful of iconic species in all of Africa. It was how we, among many other clients, got into the remote area. I started to call them the “flyboys,” and I’m hoping that the nickname sticks.

Zambeze Delta Safaris, and the work that Mark and his talented crew have been doing, has become somewhat of a beacon for modern-day conservation success stories in Africa. In fact, it could be argued that this is the most extraordinary wildlife comeback story in history. Spend a few hours on the flood plains and you’ll see the results for yourself: massive herds of Cape buffalo, reedbuck, zebra, sable, impala, hippo and waterbuck, plus a handful of other species in the more forested areas such as bushbuck, suni, warthog, red duiker and leopard. Their practice of sustainable take hunting, including archery, has allowed them to fund the crucial anti-poaching operations that pretty much run around the clock. But in such a pristine, remote and thriving part of Africa, one key species was missing: lions.

While historically they were present, the big cats fell victim to the same fate as many other species during the civil war, and were all but gone from the area. This was a reality that the Cabela Family Foundation became determined to change by writing a new chapter for their brand and for conservation.

“Our foundation had been around for 20 years or so before we took the company public, and it was set up by my folks to give back to the things that made them a success, things like hunting, the outdoors and wildlife. In the early years people sent in requests, we reviewed them and we wrote checks, but we never really got involved. When we were in the process of selling the company, I went to the board and said, ‘We need to do some things where we’re involved and participating to really make a difference. That’ll be our new brand.’ That’s what we’re focused on now — actively taking part in conservation projects. So, when Ivan Carter came to me with the idea for the 24 Lions project, he said, ‘You’re going to be there, you’re going to participate in the whole thing and get your hands dirty.’”

It aimed to be the most ambitious lion reintroduction of the modern era, and the inaugural project for the Cabela Family Foundation as participants. Fraught with obstacles from the beginning, staunch front-line conservationist Ivan Carter helped steamroll the project forward, and with the operations help of Zambeze Delta Safaris, it all came together. In 2019, 24 lions were released into the wilds of Coutada 11. Through a combination of plentiful game and pristine habitat, as well as tireless efforts to monitor the lions, prevent poaching and mitigate human-wildlife conflict, that number has risen to over 70. If the project continues on this trajectory of success and the lions breed to take up the full range of the ecosystem, then it could effectively increase the global wild lion population by 10%.

In a world of conservation losses, it’s nice to be able to point to a win like this one. But that’s not why we were there. After the success of 24 Lions, Dan, Ivan and Mark wanted to try something different: attempt a similar repopulation in Coutada 11, but this time with cheetahs. While cheetahs are more docile and easier to deal with than lions, they are also more fragile, and thus less impervious to stress and difficult conditions, and are not as adaptable. If successful, it would be the largest translocation of cheetahs in recent history.

Back at the airstrip, I swatted another mosquito away. To my left, Byron Pace — Director of Conservation for Modern Huntsman, my business partner and Scotsman at Large — loaded a roll of Kodak Tri-X into his 35mm Nikon F2, advanced to the first frame and clicked the shutter in the direction of two R44 helicopters sitting in the hangar. Flyboy toys.

Waiting at a bush airpstrip in Africa is always exciting to me; each approaching aircraft brings different faces, fresh supplies and ultimately a new adventure. It is the calm before the storm. This particular storm approached in the form of four charter planes roaring one-by-one onto the red dirt runway, coating our clothes and lenses with a familiar chalky patina. The doors opened, and chaos ensued with nearly 30 people piling out: a large faction of the Cabela family, biologists, cheetah specialists, journalists, government officials, and last but a far cry from least, 12 crated cheetahs very much awake and ready to get the hell out of there. Instantly the friendly reunion morphed into a high-intensity situation, as we had to get the animals to their temporary enclosures, called bomas, essentially open-air fence enclosures, where they would acclimate for six to eight weeks.

Shortly thereafter, a caravan of eight Land Cruisers rolled slowly down the dusty roads toward the boma with a mixture of urgency and elation. At the instruction of several biologists and cheetah specialists, specific pairs were brought into individual pens to be released together. One by one, the gates of the crates were lifted and the cheetahs came ripping out at full speed and snarl. Try to imagine what it’s like to stand two feet away from a cheetah exploding out of a crate, then double that. It’s startling, and it’s hard to photograph.

Different stakeholders involved in the project took turns letting the cheetah out of their crates — first Dan and Mary, then a few government officials, which was significant because many different demographics came together to make this happen. Then it was Mark and Ivan’s turn, and finally some of the biologists’. It was high energy for 30 minutes or so, then the cats calmed down and started to rest in the shade. We broke out the beers — champagne for Mary — and all stood in collective awe of these beautiful cats that held so much hope for the free range expansion of the species. The sun sank quickly as the mourning doves started to sound off, and just like that it was done.

“That was fast,” Byron said to me. But we were yet to learn of the year-long process of planning, permitting and praying that went into this before the planes even landed.

Later at dinner, Dan explained, “This started as a study, and looked back historically, to see if cheetahs occurred in the area. You have to start there, because if you don’t have the science foundation, you can’t do any of the logistics. So for the first eight months to a year, that’s what happened. Once we established that they were here, we started to bring in experts and build the logistics package. But we were working on this up to the last minute, and they literally handed us the final permits on the plane before we took off.” While the cheetahs were safe and healthy in the bomas for now, the real work was about to begin, and the conclusion of this matter would come months later when the cats were ready to be released. Now it was time to wait, and learn.

Over the course of the next week, Byron and I dove into the details of this project, got to know the Cabela family and met the interesting cast of characters that I started to call “The A Team:” Willhelm, the young and tenacious big cat biologist; Dr. Joao Alameda, the Portuguese veterinarian who looked like a professional soccer player; Vincent, the cheetah expert with the best sense of humor in the bunch; Poppy, the charming yet stern camp manager/mom who kept everyone in line; and Dan, his brother Dave and his family, his sister Carolyn and her family, and of course the ring leader of them all, Mary.

There were a handful of other journalists and filmmakers there to document all of the activity, and we had to have nightly meetings to sort through the logistics of who was doing what on which day. There were to be daily helicopter missions for various collarings of lions, leopards and even elephants, as well as anti-poaching patrols, deliveries of meat to the local communities, clinic visits, and tours of the community farm and beehives to see how the harvest of rice and honey was coming along — all things made possible through the support of the Cabela Family Foundation, as well as additional revenue brought in through sustainable hunting. Byron and I decided to divide and conquer, as there was no such thing as a short straw with this itinerary; all of the activities were once-in-a-lifetime experiences.

First priority was to replace the GPS collars on a few lions that had malfunctioned. As we geared up, I may or may not have yelled, “Get to the chopper!” in a Schwarzenegger voice. I’d been in plenty of helicopters before, but I had never been a part of a tracking and darting mission. We raced over the delta to an area where the last signal from the lion was received and started to circle low, using the wind from the rotors to try and push the lioness into the open. After blindly searching for nearly 20 minutes, we began to lose hope of finding what was essentially a straw of hay in a haystack.

Then, in a flash, the lioness appeared, and as soon as she made a break for it, Pete the pilot quickly swooped after her and Dr. Joao shot and perfectly placed a tranquilizer dart in her hindquarters. In six minutes, she was down. Jaoa placed a hood over the lion’s head, the other chopper with Dave’s family landed, and they were all able to get close and lay hands on the cat that they had helped bring to these plains. The collar was replaced and medicine administered, and from the safety of the air we all watched the massive cat wake up and run back into the wild. It was an experience that changed us all.

That night, Byron took the night shift and accompanied Conrad — the South African houndsman who wore no shoes, had a massive beard and legitimately carried a spear — on a leopard darting expedition. The next morning at breakfast, Byron reported that things had gone smoothly, until they didn’t. After using the hounds to track and tree the leopard, they’d darted it, then stood under the tree with a net to prevent injury to the cat when it fell from its arboreal throne. When the leopard hit the net, it woke up and started screaming and trying to claw its way out. It is said that every one second of a leopard attack accounts for 120 stitches, so naturally it would be Conrad who grabbed it by the tail to prevent its escape and remain unscathed. Let’s just say that holding a wild leopard by the tail has a short shelf life, and it managed to scamper up another tree before the tranquilizer finally set in. Ultimately, they got the tracking collar on it successfully, and probably had nightmares about the sounds of leopard screams. OK, maybe I lied — there was a short straw on these assignments, and Byron drew it while I slept peacefully in camp.

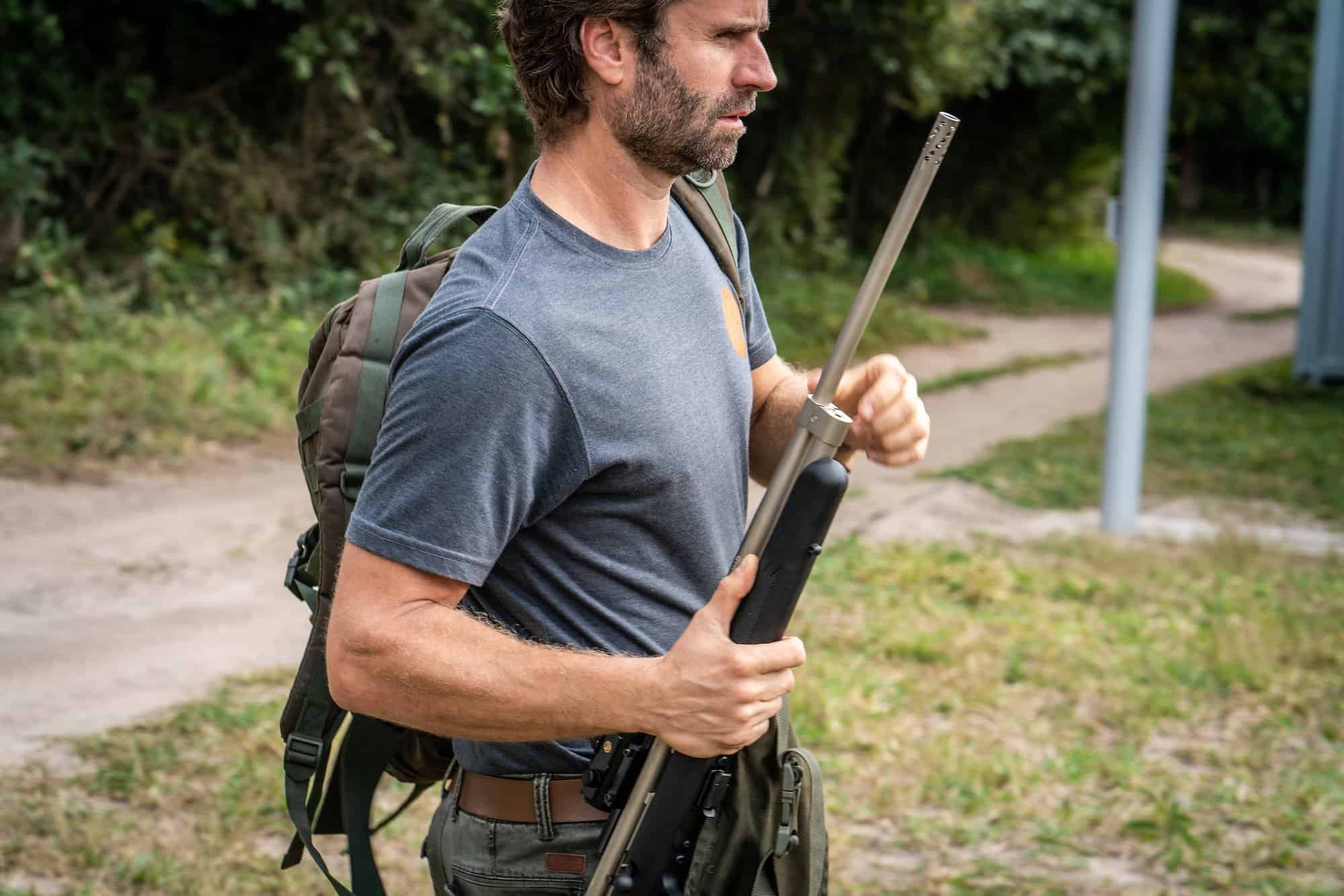

With this being a hunting area, there was still plenty of plains game to be pursued, and Dave’s teenage daughter was able to take down a beautiful old warthog with her bow. Other family members brought in reedbuck, sable, bushbuck and impala, all of which were excellent table fare at the end of long days — the best part of a safari in my opinion. The cheetahs had to be fed fresh meat, so there were expeditions every few days to hunt a few gazelles and divide them into specific kilo rations based on the body weight of the individual cats. Dan was able to bring down a Cape buffalo for the all-important meat drop in the village, and we trucked it over to a common area where meat is doled out to villagers by seniority, family size and some other unspoken form of order.

Just one of many collaborative benefits that have been put in place between Zambeze Delta Safaris and the local villages, the meat deliveries are contingent upon a zero poaching policy; if anyone from the village is caught poaching, the rest of the village doesn’t get meat for three months. Since the policy was implemented, poaching rates in the community have pretty much dropped to zero. Zambeze Delta Safaris also implemented a community farm, even providing tractor and plowing equipment to get it started, and have established over a hundred beehives for those interested. That honey is now being harvested, packaged and sold as another source of income and sustainability for the area.

One of the main missions, and one that I was not going to miss, was the collaring of the first lion cubs born in Coutada 11. Since the region is a coastal delta, our helicopter missions were often thwarted by weather conditions, so it was a few days before we were able to go out. Finally, the fog cleared, and I hopped in the back of the chopper with Dan and Mary. As we passed over intricate game trails woven into the floodplains by the abundant game, the wind whipped, and my mind soared across the endless horizon. Without a doubt, moments in Africa like these are when I have felt most alive.

Using the mother’s collar data to track the cub, it didn’t take long to find them. Hovering above a small grove of palms that seemed entirely too small to hide lions, we waited until the dart of suave sharpshooter Joao took effect, then we all landed. A sleeping lion is still a lion, so we took extra precautions as we crept up. Mary came last, and Ivan escorted her to the cub that she and her family had single-handedly funded. Her face lit up, and her hand moved to her chest and then over her mouth, seemingly in awe. Mary kneeled and put her hands on the young cat. All of us watched as she beamed with pride. It was at this moment that I realized how Mary felt toward the cats; she considered them part of her pride. Not in any fanciful sense — she’s had enough encounters with wild lions to know what they’re capable of — but with a deep love and care, which is what Mary specializes in. She was showing love to a cub that she helped bring into this world against many odds. She is the mother of lions.

The reverie was broken by the need to quickly put on the collar, doctor wounds and get back in the air before the lion started to wake up. I basked in the feeling that something special was happening here, that history was being made. Back in the chopper, we hovered at some distance until we saw the young lion wake up, yawn, then trot back toward the rest of the pride with a new piece of neckwear. We banked westward toward camp, and as we flew over the verdant delta teeming with what seemed to be endless game, it was as if we all silently, collectively, felt comforted and confident in the ability of the lions, and now the cheetahs, to thrive here.

Now, as I write with cold fingers in a drafty Montana cabin on the cusp of winter, the warm nights of Mozambique and dinners with a crew of 30 seem a million miles away. But Byron and I have kept in touch with the Zambeze Delta team, and I’m very happy to report that, as of this writing, all of the cheetahs have been successfully released into the wild, have adapted well and are making successful kills on their own. There have been a few instances where some of the young males wandered too far and had to be darted and relocated to avoid any conflicts with local communities, but so far there have been no casualties or incidents. While the results of the reintroduction are yet to be fully determined, all signs point to success. When you have the dedication and teamwork from folks like Mark Haldane, Ivan Carter, the biologists and researchers, and anti-poaching rangers, and of course the support of and participation from an organization like the Cabela Family Foundation, it’s actually possible to make history.

It should be noted that conservation at this scale is exorbitantly expensive, and projects like this would not be possible without the dedication and compassion of people like the Cabela family and this entire steller crew on the ground. Between permits, logistics, anti-poaching patrols, helicopter time and fuel, GPS collars and tracking equipment, vehicle maintenance, and all sorts of other miscellaneous costs, these kinds of projects are not for the faint of heart, nor the light of coin. As a matter of reference, between the lion and cheetah reintroductions, the Cabela Family Foundation has injected roughly 3 million dollars to bring this project to bear, and to keep it going. Lastly, it’s imperative to point out that the project has been 100% funded by hunting dollars, even though these cats will never be hunted in this area.

Having spent the bulk of my career trying to communicate the nuances and complexities of hunting in Africa, why it’s necessary and the good it can do, a project like this is a perfect example. There is so much misinformation, misunderstanding and even blind bias against the notion of hunting in Africa, but organizations like the Cabela Family Foundation are helping change that reality and open up dialogue. The future of conservation in Africa lies in the ability of the hunting and non-hunting communities to work together under common cause, put aside differences and old wounds, and seek collaborative, constructive solutions. There is no other way.

I asked Dan about this, and his message was clear.

“I think that this division globally between foundations and NGOs over their acceptance of hunting is just crazy. We all want the same thing. How amazing would it be to combine resources and do this work together for a positive outcome? More lions in Africa, more cheetahs across greater range, I mean, who can’t support that? We have open arms and minds, and would love to collaborate with other NGOs who maybe in the past have had negative views on hunting, especially if it means we could drive forward positive conservation. We want to partner up and try to do some really big things in the future. That’s the goal. Why wouldn’t we all agree that that’s a good thing? Philosophical differences used to be what created great ideas. Now it’s just divisive, and we need to fix that and act before it’s too late.”

Originally published in Modern Huntsman Volume 8

Related Stories

Latest Stories