Your cart is empty

Some uncertain noise wakes me up. The first few seconds are always a bit blurry and confusing when you awake in the middle of the night. Startled, I soon realize it’s the wind pressing at the tent fabric. I am in the middle of Jämtland county, a vast public wilderness in midwest Sweden.

My backyard. The Hilliberg tent is sturdy, being of Swedish make, and I know it can handle the winds. I have chosen the spot carefully with consideration for the direction of gales, which are strengthening. Although I’m wearing earplugs, the sudden bursts and rushes won’t let me go back to sleep. I start reflecting on the fact that I am actually lying here, tucked down in my cozy sleeping bag far from any roads, people or everyday matters. I’m doing a five-day trip in the mountains in pursuit of capercaillie, black grouse, valley grouse and ptarmigan. I have been hunting this area for more than 20 years and I have come to deeply love these adventures. Some areas can be hunted on a day trip, but it feels different, better, waking up in the hunting area. The night allows me to acclimate to the rhythm of the place and get my mind right for hunting.

It’s hard to say what drives us to become hunters, and as I try to recall my early years to find my starting point, I see my grandfather’s face and know that he would have loved to hear of these adventures. The glow in his eyes is something I will never forget. I think there is a special connection between generations of hunters — a bond formed by knowledge, understanding and mutual memories that’s not found in other pursuits. So, how did it all start?

HUNTERS FORMING HUNTERS

I didn’t always know what my grandfather Nils’ cunning introduction to the world of hunting, fishing and exploration would come to mean to me. From the age of five, I remember watching him cleaning his rifles, waxing his fly lines, and telling exotic hunting stories of the past. He spoke in such a passionate way, and it was impossible to not be invigorated with the images. Nils was born in 1898, and by the late ‘70s, he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease and was no longer able to hunt on his own, even though his mind was clear. In his great wisdom, he found a way to plant that glowing seed in my mind. He told stories of great bull the 40-pound pike that he had to shoot with his 12-gauge shotgun before it was possible to lift it into the boat; and of the vibrant encounters with the great, silvery salmon of the famous River Mörrum. He lit the spark of the hunter within me, and for that I will be forever grateful.

At the age of 12, I already had a strong fascination with firearms and ballistics. Making black powder and building my first shootable gun was something I never thought would end up in my curriculum vitae, but it brought about my relationship with Donald. He was a sharp old man who built key-harps, violins and, most importantly to me, gunstocks. His workshop lay on the route I biked to school, and after months of seeing my gloomy face peer through the window of his workshop, he invited me into his room of magic. The mighty feeling of entering what seemed a mystical church from the medieval ages was something I will never forget.

Then and there, I understood my calling. Making decisions based on deep desires, beyond financial goals, and acknowledging passion and prehistoric urges was the most important lesson of my early years, imparted by these mentors. With my hunting and gunmaking fascinations combining, the distinction between work and freedom was forever blurred. The final drop was poured into the pan of life, and my days have been filled with joys, dreams, hardships and friendships ever since.

HOW HUNTING AND THE MOUNTAIN YEARS HAVE CHANGED MY PERCEPTIONS

I must confess that hunting had little to do with carrying on traditions, respect or humility when I was young. It was all about getting to that moment when I could pull the trigger. The thoughtless eagerness of youth was bliss in many ways, but it definitely wasn’t the way to achieve a successful hunt. Only gradually did I realize that harvesting the game was just a small part of the whole. We always took care of the meat and skins of the animals, and preparing the meals soon became an important part of the “why.”

I grew up in the southern part of Sweden, where hunting wasn’t exactly a grand adventure. It was mainly stalking ducks and geese, calling for roe deer during the rut, driven hunts for hare, fox and roe, and the yearly moose hunt sitting in a stand. It was never that far from a road.

I vividly remember thinking there had to be more to it than that. My best friend and I spent nearly all of our time in the forest looking for whatever game we could harvest and cook. We built huts in the woods and took long hikes to unknown territories, always carrying our air guns, bows or slingshots. I wanted the hunt to be so much more than waiting for an animal to come by the stand I sat in. I wanted to be an active part of the process and for success not to be some fluke, but something worked for.

THE SENSES ACQUIRED

In exploration, I came to understand that there is more to the stories of the past than simple tales. The words of my grandfather began to ring differently in continued retrospection — they all had a kind of hidden message. As I grew as a hunter, I was looking at nature in a different way. It had to do with how I processed the information from my senses.

Sight: I read the foot, paw or hoof prints in the areas I hunt and remember the paths they take for following years. I pay attention to weather and winds, to signs of mating and antler scraping. I watch, always, for the feeding and bedding areas — the signs of the animals’ homes.

Smell: Discerning the scents of the animal landscape is not a quick nor easy skill to learn, and many overlook it. I remember telling a fellow hunter that it smelled of capercaillie during a stalk with my pointers. He laughed. It didn’t take long before the dogs were pointing and a grand rooster took to its wings. I didn’t smell the bird itself, but the fragrances from the right herbs, trees, and humidity, when all put together, told me there was a bird right under our noses.

Sound: It takes a good ear to listen and mimic the sounds of the animals, and I fear the day my hearing isn’t with me anymore. That learned knowledge, to me, seems like a necessity to be a part of and interact with the creatures I’m hunting. Calling has always been an integral part of many of my pursuits in Sweden. But that intentional listening is not only important to be a better animal. Plenty of lessons are picked up from hearing other hunters. Taking your time to learn from the mistakes and success stories of others is a fountain of knowledge. Getting to follow someone with a deeper connection, themselves, to the area and the game is a beautiful thing.

LEARNING THE FOREST TOGETHER

I remember a time I was stalking behind my dear Sami friend Habbe during a moose hunt. I was teaching him how to call moose, but more important, as it turned out, was what he taught me. As we strolled along, I saw him break twigs off of fir trees that we passed. At first I didn’t want to ask, but after a while I couldn’t resist. The answer came swiftly: “I don’t know when I might have to stalk through here next time, but I will surely make less noise then than I do now.” It was a revelation to me at the time. The Sami people are reindeer herders and live by the rules of the forest and the mountains. He and his ancestors before him always needed to plan ahead, and ahead doesn’t necessarily mean for the next months. It could mean helping oneself years down the path. “It takes three years to create a trail,” Habbe said. “After a while, the animals start using it. They then help me finish the trail I started making. This helps us both.”

I have realized that knowing the behavior of the animals has made a huge difference in how I go about my hunting. I often mimic the sounds of several animals interacting when calling moose, for example. This makes hunting in new areas a fact-finding mission before anything else. Finding and understanding the do’s and don’ts has broadened the hunt to something much more vast and complex than what I experienced as a young boy. Bringing these sensations and subtle keys together is probably the closest thing possible to attaining an elusive sixth sense.

FINDING MY PLACE ON EARTH

My personal inspiration and insights gathered from all the above led me to new hunting grounds. When it was time to launch my gun shop in the late ‘90s, I thought deeply about what was essential to me. I realized that starting down in the urban South would place me 850 kilometers from where I wanted to wake up each morning.

A year later, I opened the doors to my first workshop on an estate about 25 kilometers northeast of Sweden’s largest skiing resort, Åre. One thing led to another, and in combination with my craft as a gunmaker, I started working as a hunting guide and shooting instructor. One could say that guns and hunting became my life, and to top it off I have led it in one of the most awesome places in northern Europe — an expanse filled with public lands for hunting and creeks full of trout.

I was by no means the first to set foot in this area seeking adventure and a free lifestyle; many prominent people have traveled far distances to quench their thirst over the centuries. Even Sir Winston Churchill spent time in the area, along with a long line of English noble sportsmen of the era. But there is one big difference: they all had to leave, while I got to stay.

FINDING THE ELUSIVE CAPERCAILLIE

The fascination with the creatures of this land led me to get pointing dogs and to start calling moose. Autumn was filled with days among the glowing birches as the landscape shifted colors and finally let the leaves blow free. Darkness and winter would come, covering the landscape in deep snow. I had heard and read much about the winter hunting for capercaillie and grouse. I had even tried and failed at it, but was persistent in learning. I started following experienced mountain hunters and poring over maps. I had to find the places where pines grew on the edges of marshlands, or high country that gave me glassing advantages.

About 20 years ago, I found an area that has kept calling me back. It has everything: old gnarly pine trees, vast marshes, and plenty of capercaillie.

THE HUNTING

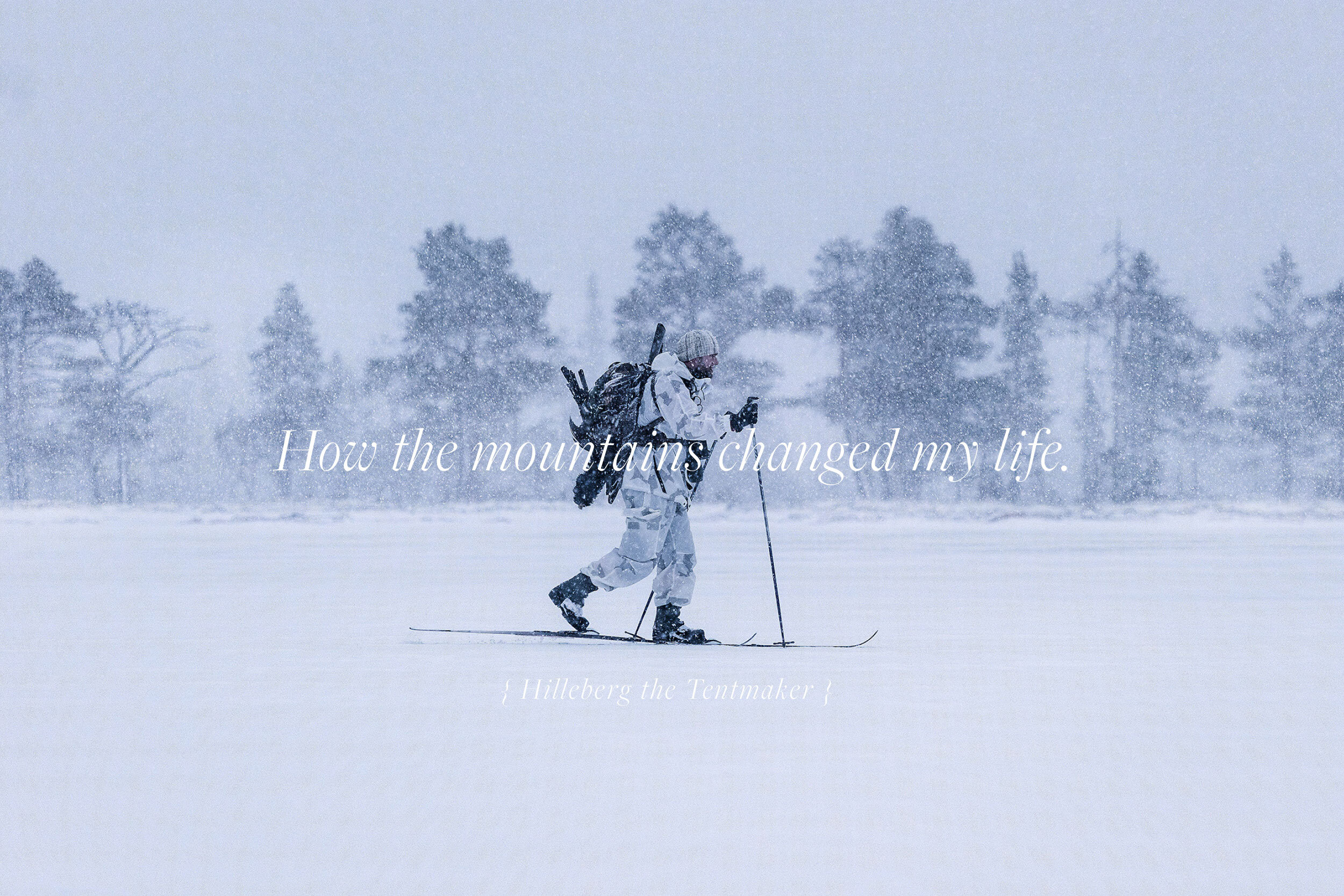

My skis push forward through the snow, my binoculars wait at my chest — we’re scouting every tree. Conditions are not in our favor as the winds are harsh and the snow is sharp. We’ve only seen a few black grouse, but I am happy to be back in this favorite area, with my friend and photographer Hans Berggren.

We’ve camped in the open marsh, and ski out to search a few of the capercaillies’ feeding spots. They have their favorite trees: pines with higher sugar levels that they keep in their memory. We know where to look. But day goes by and no birds are found. The late winter’s been strange. Temperatures as high as +7 degrees Celsius, with rain and hard winds, melting the snow to the ground where the birds can feed right off it. I can’t help but wonder how this form of hunting will be affected during the decades to come. What will our winters look like in the future? I am saddened by the prospect that my future grandchildren might not be able to enjoy this endeavour, but I won’t let the despair linger.

Nevertheless we push on, tiring from many kilometers of skiing, shoulders fatigued by heavy packs. Somewhere in the back of my head, a grinding thought is brought to life. The final hour of the day has so many times been the moment of success. As light fades, we decide to make a final push with what energy we have left. Out of nowhere, two male capercaillies appear over the treeline. They see us through our camouflage and turn. Here, the experience from years prior kicks in. I know they will not fly far, and as we creep through a grove, we spot them in the treetops a few hundred meters ahead. There is no time to lose. They are agile, but I have to give it a shot. I find a pine tree to use as cover, and close the distance as much as I dare. I range 264 meters from where they sit. I lie down against my pack and carefully take aim. My pulse rushes. I gauge the side wind, aim just on the edge of the bird, and take a final breath. In the crack of the rifle, I lose sight of it. But it felt like a good shot. Hans sees the capercaillie tip over as silence returns to the marsh

It’s hard to describe my feelings as I move toward the place where it lies. There is no more fatigue. The memory from the hours prior plays like a film in my mind, and once again I feel thankful for the knowledge passed on to me and the insights I’ve gathered myself. Put together, they led to success. Darkness settles quickly, and on our return to camp it is completely dark. After a quick meal and a sturdy whiskey, paired with some smoked moose heart, we collapse. Since nights are long here in January, we have nearly eleven hours until it is time to wake up again. We decide to have a feast the following morning to celebrate, and sleep comes easy.

MOUNTAINS ARE CALLING

We gorge on a stew of the lean meat with lentils, chilis and red rice, and pack our gear in the sleds to go farther into the mountains. The sleds follow us easily over perfect snow, and a few hours later we arrive at the last birches on the foot of Mount Santa. Preparing dinner in the dark, we hear grouse chuckling nearby.

I unzip the tent fly to find no less than ten valley grouse just meters from where we were sleeping. They sound like they’re laughing as they take off. Valley grouse and ptarmigan have different cackles, so even in the early morning they are easy to recognize. All the way up the mountain slopes, we hear the shouts of both species out of sight. I hunt with a small-caliber rifle in .22LR, which is accurate, but sensitive to the winds. Unfortunately, there is no lack of wind, which shifts fast in direction and intensity.

We fight it, climbing higher and higher, above the valley of Lundörrspasset. It forms a deep pass between the higher mountains, the Fjäll. Such passes can be treacherous, as the winds compress into them and rush to incredible speeds. This hangs in our minds when we pitch our tents. Reindeer, too, are feeding here, and we travel to stay clear of them.

Disturbance might push them to another area, making it hard for the herders who look after them. The wolves give those people enough trouble.

But there’s always an abundance of grouse where the reindeer have fed. They scrape through the snow to eat at their favorite lichens, which opens up the bare ground for the grouse to find food, in another perfect cooperation of nature’s species.

Suddenly, I spot a couple of round, white balls on a ridge a hundred meters away. We stalk carefully and keep low. I don’t use winter camouflage when grouse hunting. I have this idea that they get nervous when they can hear but not spot a stalker, so they maintain a safe distance. They use camouflage themselves where other animals don’t. That is their advantage. What they do not know is the reach of the .22LR, and I manage to get the first bird of the day.

While holding this beautiful creature in my hands, I can’t help but feel whole and a part of the brilliantly complex ecosystem, tuned into my own senses to be the best animal I’ve developed to be. I take responsibility for the meat I eat, and in doing so, I get to be a part of the past and the future. I get to be the person I want to be and live the life I want to live.

It’s clear to me that my development as a person, craftsman and hunter is all delicately woven together. All are the fruit of time and effort — listening, trying and learning. The dedication to following my path, the trust I’ve put in my senses, and reflection over the differences in life — while keeping an openness to newness — have formed the layers of my knowledge. Combined with self-reliance, stubbornness and sacrifice, it’s shown me an alternative way of measuring success and reaching contentment. It’s why I will remain a hunter for the rest of my days.

Related Stories

Latest Stories