TEXAS | Gulf Coast

The Texas coast is a lesson in contrasts, a glaring representation of the state’s great diversity. There is an incredible beauty to this desolate stretch of land, marked by salty marshes and low-lying barrier islands, and for anyone who has spent time here, or was raised here, it becomes a place unlike any other. If you are away for too long, you miss the damp, heavy air, thick with salt that sticks to your skin, and the smell of the hyper-saline bays and estuaries between the barrier islands and the mainland.

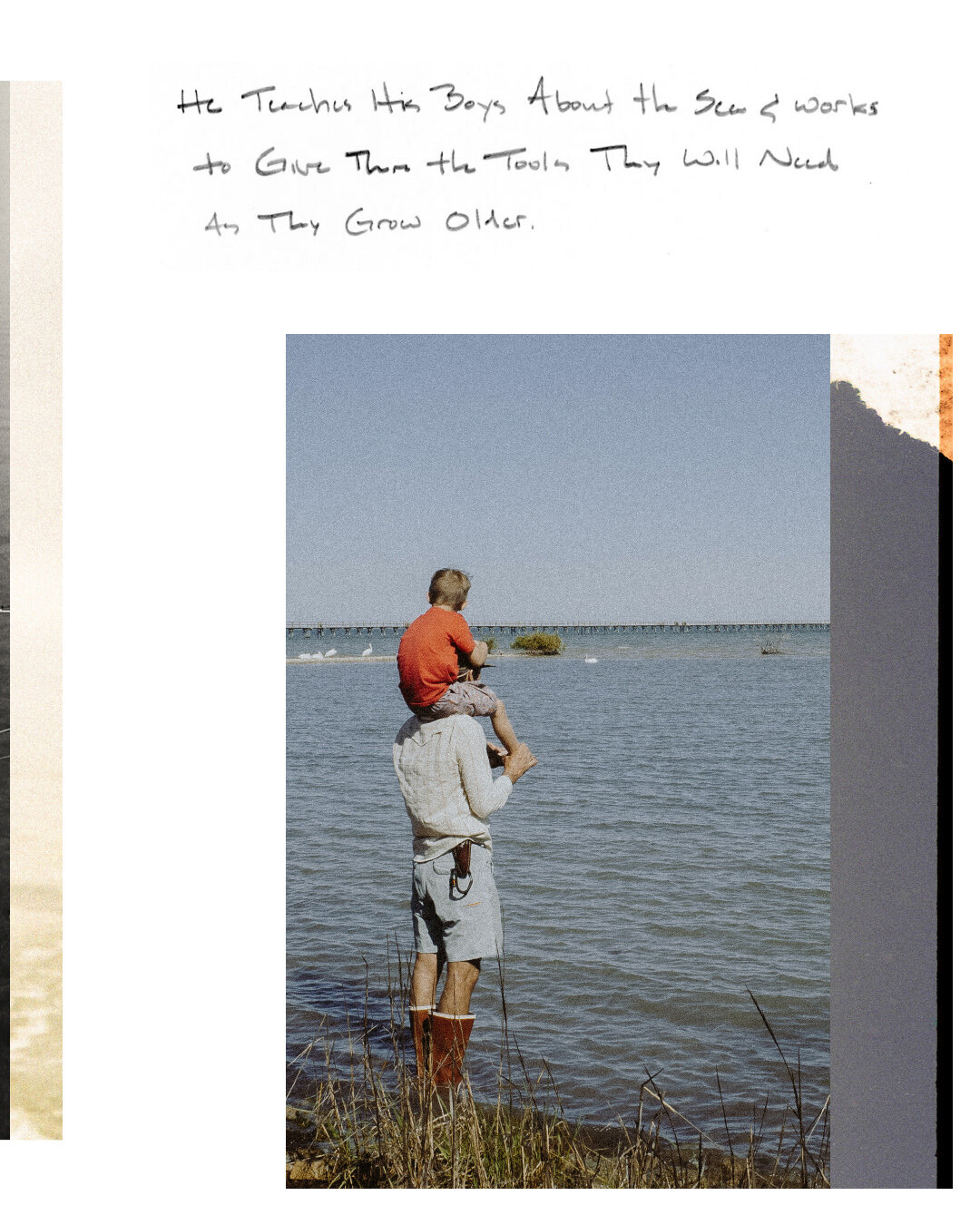

You miss the shrimp boats tied to the pilings and the pale green color of their nets and tackle in the summer sun. You miss the sight of spoonbills and the flocks of green-winged teal, the whooping cranes and the sound of honking overhead as Canadian geese head north in the fall. You miss the thin, distant horizons that seem to rise out of the sea when returning from an offshore fishing trip on the Gulf Stream. You miss it all, and I know this because I spent the early part of my life here, and then I left. I left for a long time, and while I would find myself in some distant country, maybe on a long, endless track after buffalo in the dense sand of the Okavango, or up in the north country on an equally endless pack trip to some distant mountain, my mind would wander and I would feel the warmth of the south Texas sun on my skin and dream of the day that I would be back among the shrimp boats and the coastal dunes of my beloved shoreline.

The Gulf Coast has attracted many to its waters. It began with the Spaniards and Cortés, and later Pineda, and the legendary shipwrecks of the conquistadors in search of gold, eternal life and new worlds. But they were not the first...