Your cart is empty

Hunting is a profound human activity that has been with us since the dawn of man. It is practiced today by millions of people worldwide and remains a longstanding outdoor tradition, out of both recreation and necessity. However, its perception in modern society has become muddled as more communities drift away from the need to hunt, fueled by misconceptions of what it means to harvest an animal. Today, we hunters are a minority. Therefore, it is now more important than ever that we adhere to a strict code of conduct, which requires respect for the animal and builds equity in the minds of a public that is becoming increasingly hostile to this lifestyle.

In 1887, at the very first meeting of the Boone and Crockett Club, the founding members discussed the need for a new standard of ethical hunting. The name given to this standard by the Club was Fair Chase, and it has become a guiding principle for the pursuit of wild game, a code that I have applied earnestly to my life’s passion. It dictates that hunting should be conducted by responsible people who hold themselves accountable to a higher personal standard that extends above and beyond the law. The Fair Chase principle contains three fundamental components: Intrinsic Value, Moral Legitimacy and Ethics. I believe that an understanding of Fair Chase in today’s world is paramount for an accurate representation of hunting’s place in social discourse and raising awareness to its truth will protect the sportsman heritage for those yet to experience it.

This is the understanding that every being has value in its own right, which is not derived from the human benefit they can or cannot be used for.

The principles I hunt by have developed over time, and the first I chose to live by was responsibility, born out of respect for the wildlife. In my youth, I was fascinated with the nature of animals — from ants to grasshoppers, bears to tigers, even dinosaurs. I recall asking my dad if a bear and tiger got into a fight, who would win? A legitimate question as an eight-year-old.

“True sportsmen must always hunt hard and fair, with honor and purpose, never take wild game or the opportunity to hunt them for granted, and ensure a future for both.”

My father loved to hunt pheasants, and even before I was old enough to carry a gun in the field, I walked alongside him and my interest in wildlife focused on the animals we could hunt. This fascination evolved into an appreciation for game animals, specifically. Just laying eyes on these creatures in the wild was a precious victory and notched a memory. Once I was of age and earned the right to hunt, I harvested my first pheasant, and appreciation transformed into responsibility. This notion of responsibility represented the bulk of my father’s teachings when it came to wildlife and their home.

I can recall his early lessons about “this is how we do things and this is what we don’t do.” Although I didn’t connect the dots at the time, I later realized he was teaching for the sake of continuance — teaching me to respect the privilege to hunt so we can continue hunting for generations to come.

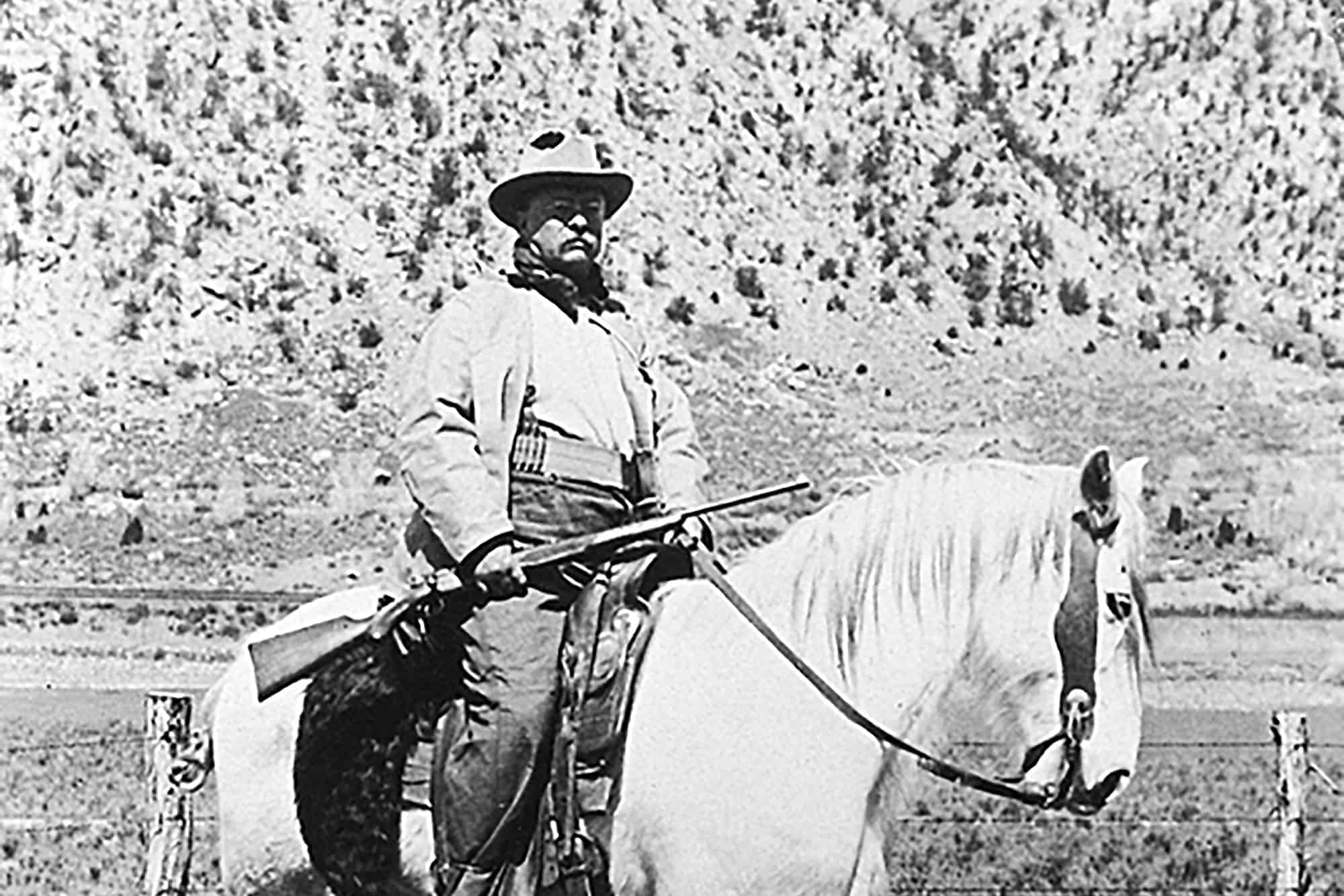

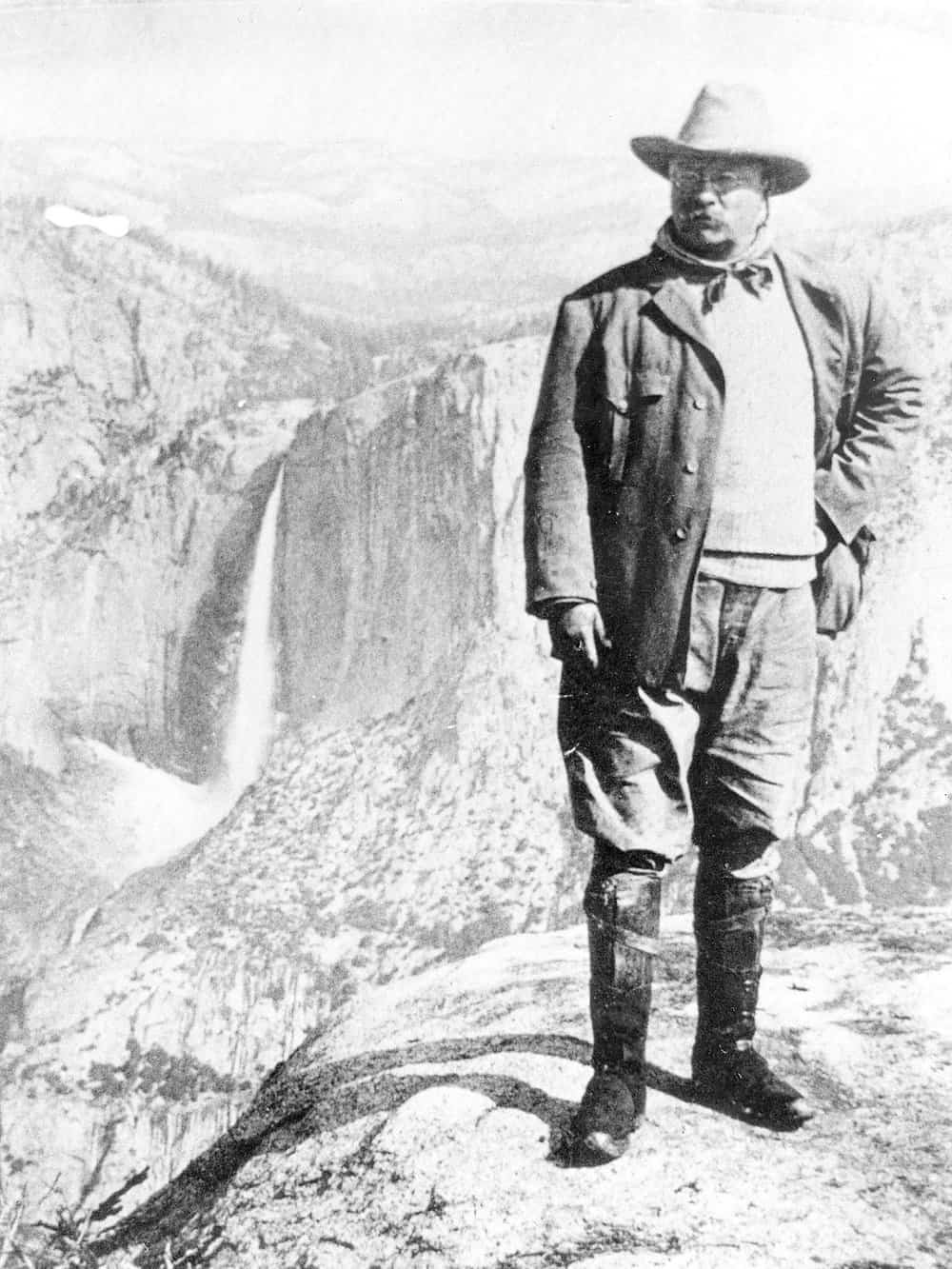

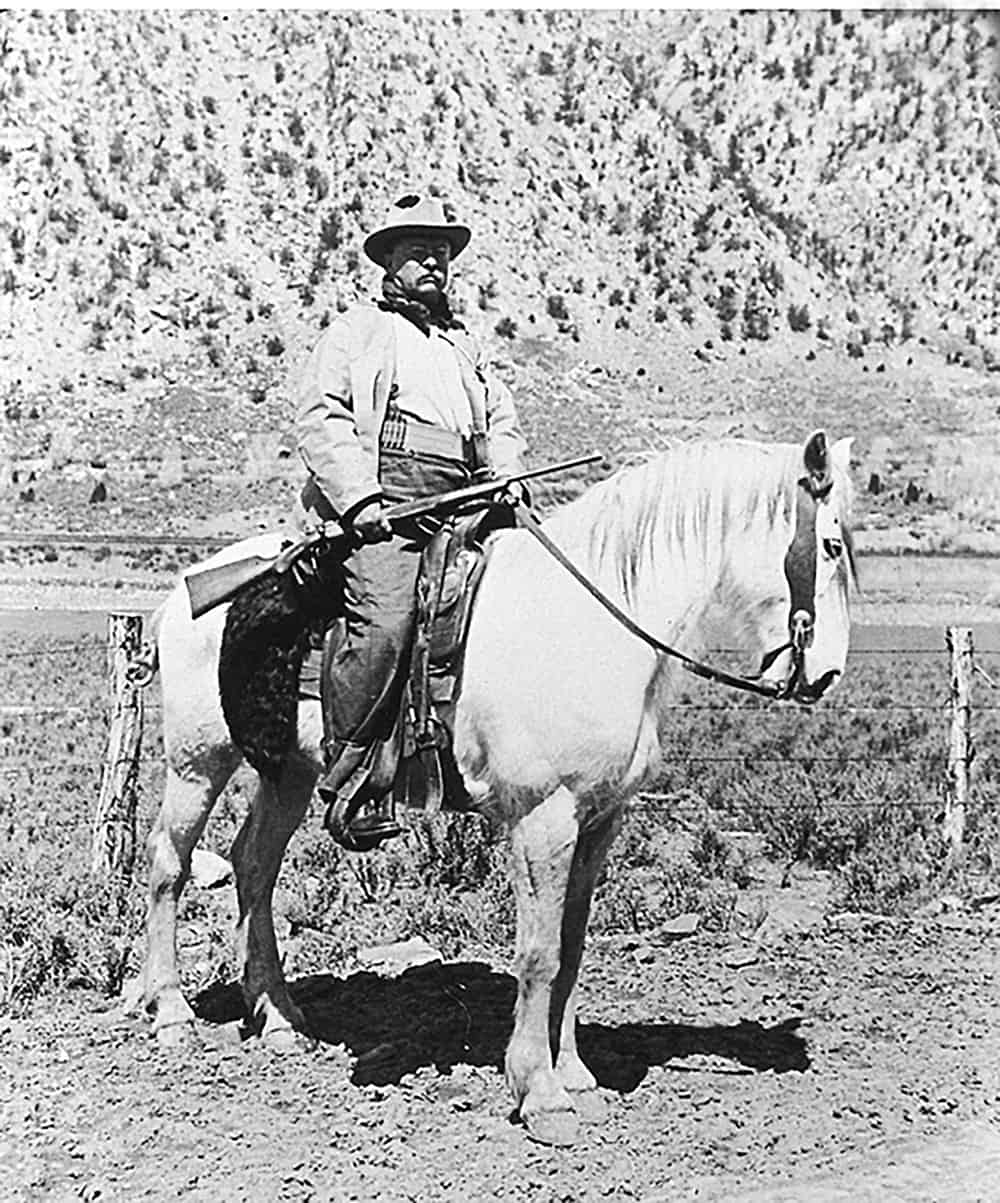

Theodore Roosevelt is not just remembered as as one of the founding members of Boone and Crockett. History has shown him to be one of North America’s great conservation heroes, leaving a legacy of more than 230 million acres of public land established during his presidency. He relentlessly put conservation first, insistent that natural resources should be managed rather than exploited.

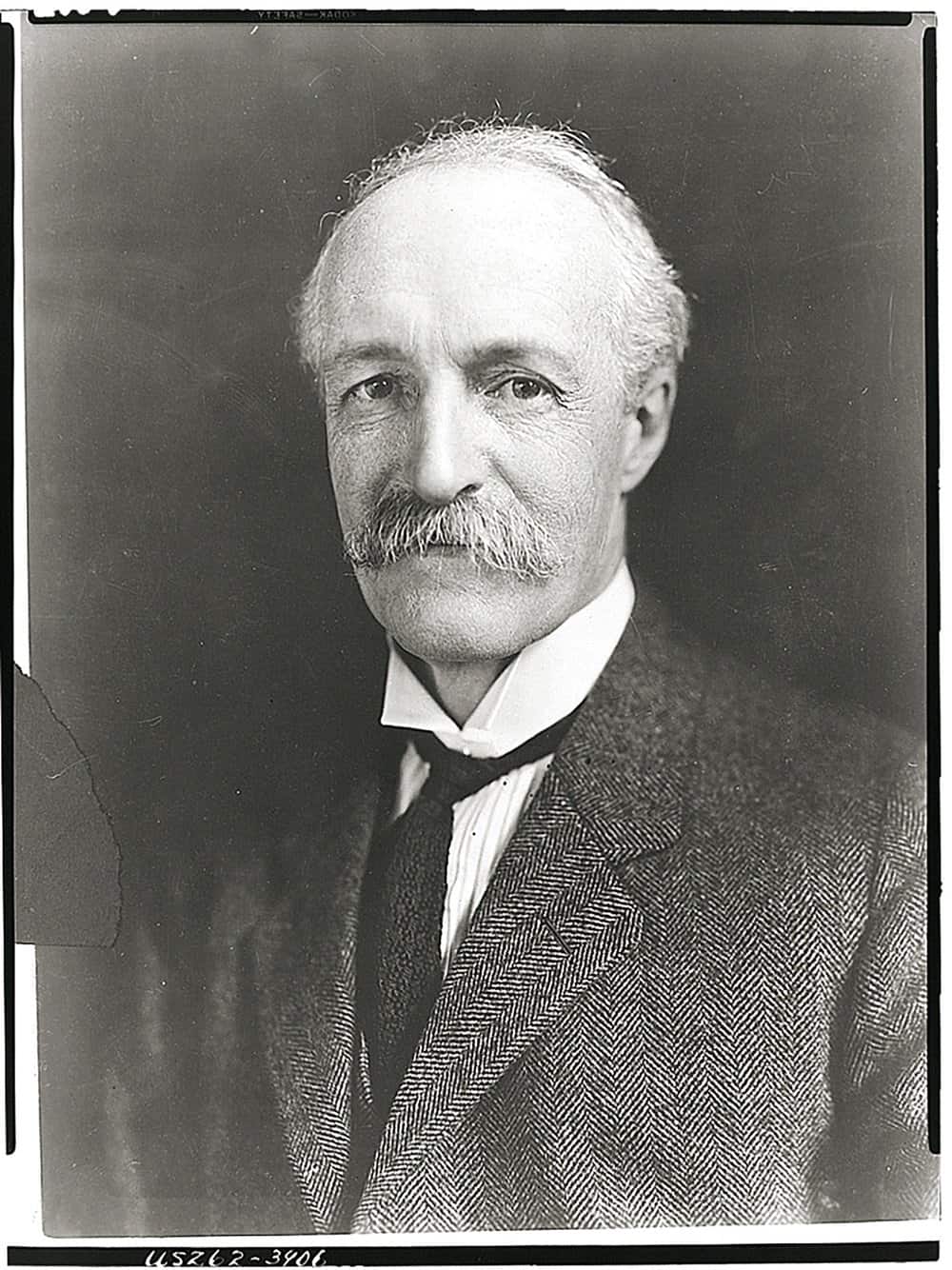

One of the Club’s earliest members, Gifford Pinchot joined Boone and Crockett in 1897. He was a devout forester and set policy as head of the United States Forest Service during the department’s infancy in the early 1900s, firmly believing that the country’s vast forests were a renewable, profitable resource meant to be managed by the federal government, rather than private holdings.

Some have emotional qualms about wildlife being killed for any reason. It appears that these same people are unconcerned if wildlife dies at the behest of nature, just as long as hunters are not involved, and certainly not if they enjoy it. This ideology stands ground regardless of the fact that the source of enjoyment is from the process and the effort involved in the hunt, rather than pulling a trigger or drawing a bow.

This raises an important question: Do we care more about the game itself or just our ability to hunt it? The answer used to be simple but is now clouded in the current climate of hunting resistance. It is easy to get caught up defending something we like to do and lose sight of the animals we pursue. There simply must be a moral legitimacy to hunting if it is to remain socially acceptable. Everyone values wildlife in their own way, but a deep connection is forged while engaged in the hunt of a wild creature. Bringing a harvest home to provide nourishment for oneself and loved ones creates a level of respect for an animal that only hunting can truly provide.

True sportsmen must always hunt hard and fair, with honor and purpose, never take wild game or the opportunity to hunt them for granted, and ensure a future for both. This leads to the ethical treatment of game in their natural habitat and to hunters becoming participants with wildlife rather than its master.

A hunter’s values, what motivates us and how we conduct ourselves, shape society’s opinion of hunting. If we falter while striving for excellence in the field, the public will lose faith in Fair Chase. Traditions could be at risk if a majority of citizens develop a negative perception of hunting and fail to recognize the benefits provided to wildlife populations. We must not allow this to happen.

When I pursue an animal, I believe that it deserves my best and most honest effort. Cutting corners to make hunting easier and to assure a successful outcome undermines the unique nature of the pursuit, which offers “no guarantees.” By definition, to hunt is to pursue, which may or may not result in a kill. Any animal I take deserves to die quickly and humanely, just as much as they deserve to live wild and free. How an animal lives is just as important as how it dies. Fair Chase stresses the importance of hunting wild, free-ranging game animals as opposed to those confined without a chance to elude the hunter. This is where responsibility to myself and the game I seek connects.

Fair Chase is the confluence of intrinsic value, moral legitimacy, and ethics. A conversation about ethics in hunting, the use of wildlife, and the land where wildlife lives is pertinent to the public image of hunters and hunting. As sportsmen and women, we each carry an individual and collective set of values with us into the field, teachings that are instilled from fathers, mothers, mentors and personal experience that light the paths of right and wrong. These values are deeply rooted in that which makes us human — a species of hunter-gatherers. Our treatment of the wildlife we pursue and the environment in which they live are also linked to the purpose for which the game are killed: for sustenance, and fellowship. Whether it is for food, the experience of the chase, the accumulation of fond memories, or all of the above, hunting ethics are also about continuance.

History has proven that our society will eliminate or at least greatly diminish those activities seen as unethical. Therefore, society at large must be assured that hunting is something more than killing, and that hunting does not risk, but rather ensures the survival of the hunted. Through the concept of Fair Chase and hunting ethics, hunting transcends mere killing and becomes something more. That “something more” is a combination of the expectations of society, coupled with a binding contract on the part of the hunter to behave in a manner that honors both hunting and the animals pursued. The result will be a continuing social relevance for hunting in a modern world and the continued survival of the hunted in a truly wild state.

For the past 18 years, Keith Balfourd has served as Director of Marketing for the Boone and Crockett Club. He lives, hunts, fishes and teaches spey casting with his wife and two daughters in Florence, Montana.

This story was originally featured in Modern Huntsman, Volume Three: Wildlife Management

Related Stories

Latest Stories