Your cart is empty

My first deer camp was in 1970. An old logging shack warmed with a 30-gallon fuel drum converted to a wood stove; red wool clothes drooping the ropes where spare socks dried and hunters warmed between drives. My dad, whom I bragged about as the greatest deer hunter in Koochiching County, spent months planning deer camp. My favorite camp mates were Grandpa Walt and Uncle Marvin, Dad’s older brother. Coming and going were assorted friends and hungry employees scraping by as timber fellers in Dad’s logging business.

Only six years old, I couldn’t understand it all, but it was formative. Even at my young age, I detected joviality beyond what my eyes had heretofore witnessed. The language was a bit rough for a kid, though the treats were aplenty.

Big smiles grabbed my cheeks when Mel would draw the accordion from its case and bar music filled the air. It was so hot inside we’d have to open the shack door, though I suspect mostly to clear the cigar smoke to a breathable toxicity. I remember laughing with the adults, though I was too green to understand the punch lines. Each elder made sure to compliment my hardiness, with my kindergarten mind unable to absorb the charity of these accolades.

Dad was having the time of his life. My mind was set; I would be a hunter.

A month after that ontogenic deer camp, a once-in-a-century winter decimated Minnesota’s deer. The season was closed in 1971. No camp that year. I was bummed.

Before the next spring thaw, Grandpa Walt had a stroke. Grandma had her hands full. It was two long hours to the Iron Range to see them. We spent grouse opener helping winterize the dilapidated homestead Grandpa vowed to never leave; Grandma spoiled me as her sons labored. I listened as Dad and Uncle Marvin discussed if deer camp would be held in November. Eventually, Marvin opted to be the reliable hand Grandma needed for Grandpa’s care.

My first deer camp would be my family’s last, ended by a series of disconnected events. Life, as I came to learn, was not fair.

So much changed, so quickly. Dad spoke fondly of the family deer camp, speaking almost mystically about big bucks in the Sturgeon River country. He’d often pause, light a cigarette in his now-tremoring hand, then look down as he inhaled, as if something lost should be right there between his feet.

In his silence, I knew he was considering the reality of his now-broken life — recently divorced, fighting the bottle, adrift since his dad had died four years after that last camp. Every path he searched for explanation seemed to dead-end.

Deer hunting was the last grasp of what his life had been, or could have been. I can’t trace his downward spiral to the end of that deer camp. I do know he missed it dearly. He picked up what pieces he could and filled some voids by hunting with kids and neighbors. Never again did I see the smile he held that November. It was the week I turned six; the pleasures so obvious on his face were what cemented my hunting future.

Over the next few years, struggles with booze eroded our relationship. Good times were few, the best of them were spent chasing whitetails in Minnesota’s big north woods. Me being of hunting age was a milestone in his life. Sadly, the demons had grabbed him so tightly, the only semblance of a deer camp came from invites to join kind friends who sensed his loneliness. Offers to join other camps were not the same as hosting his own. His emptiness was easier to read than a track in fresh snow.

Yet, no matter what darkness hung over him, hunting was still his bright time, when his love to hunt could temporarily beat back his addictions. Each November, he was a different dad, and for sixteen days of the season, it was fun to be his son. Chasing deer raised his spirits — driving to stands, we talked of restarting a family deer camp. I hoped to see his blue eyes flash again with that hunting camp twinkle. But by Christmas, the bottle regained its control, and any chance for a new path had drifted over.

Thirty-three years after that last deer camp, I found myself in Colorado, mule deer hunting. Uncle Marvin called to tell me that Dad was in the hospital. It was deer season back home. Dad was now a non-functioning alcoholic, unable to even hunt. He passed after two months.

Going through his belongings, I found a few pictures salvaged from his house fire, twenty years prior. The few that caught my eye were all from deer hunts — bucks, camps, smiles, a life of dreams ahead of him, a young man unaware that his difficult life would end at age 62.

My younger siblings and I sorted for the meaningful items. I asked if I could have his old buck mount, now oiled and greasy from too many years hanging in a bar. That buck came in 1976, his last real effort to build a family deer camp. It was taken while we were hunting with his brother Marvin back home on Da’ Range, not far from where his dad and uncles had first taken them hunting. It was a fine buck for the big woods, worthy of a taxidermy bill. Mostly, it became his hope for days that might be.

I’ve since had that buck remounted. It hangs over my desk, not the biggest among many antlers and hides adorning my room, each a reminder of special times with special people. I find myself often looking at that buck, thinking about what might have been. What if he’d had those annual markers that get one through hard times? What if he’d had the family deer camp? Would it have given him purpose and strength to persevere, to overcome the cruel hand of fate that terminated his annual family revelry in the November woods?

I don’t know that answer; I never will. When I think of his pure joy and the never-again-seen happiness that owned him in that deer camp almost 50 years ago, I’m sure losing that family tradition didn’t help as he traversed a life more difficult than any man deserved, however self-inflicted.

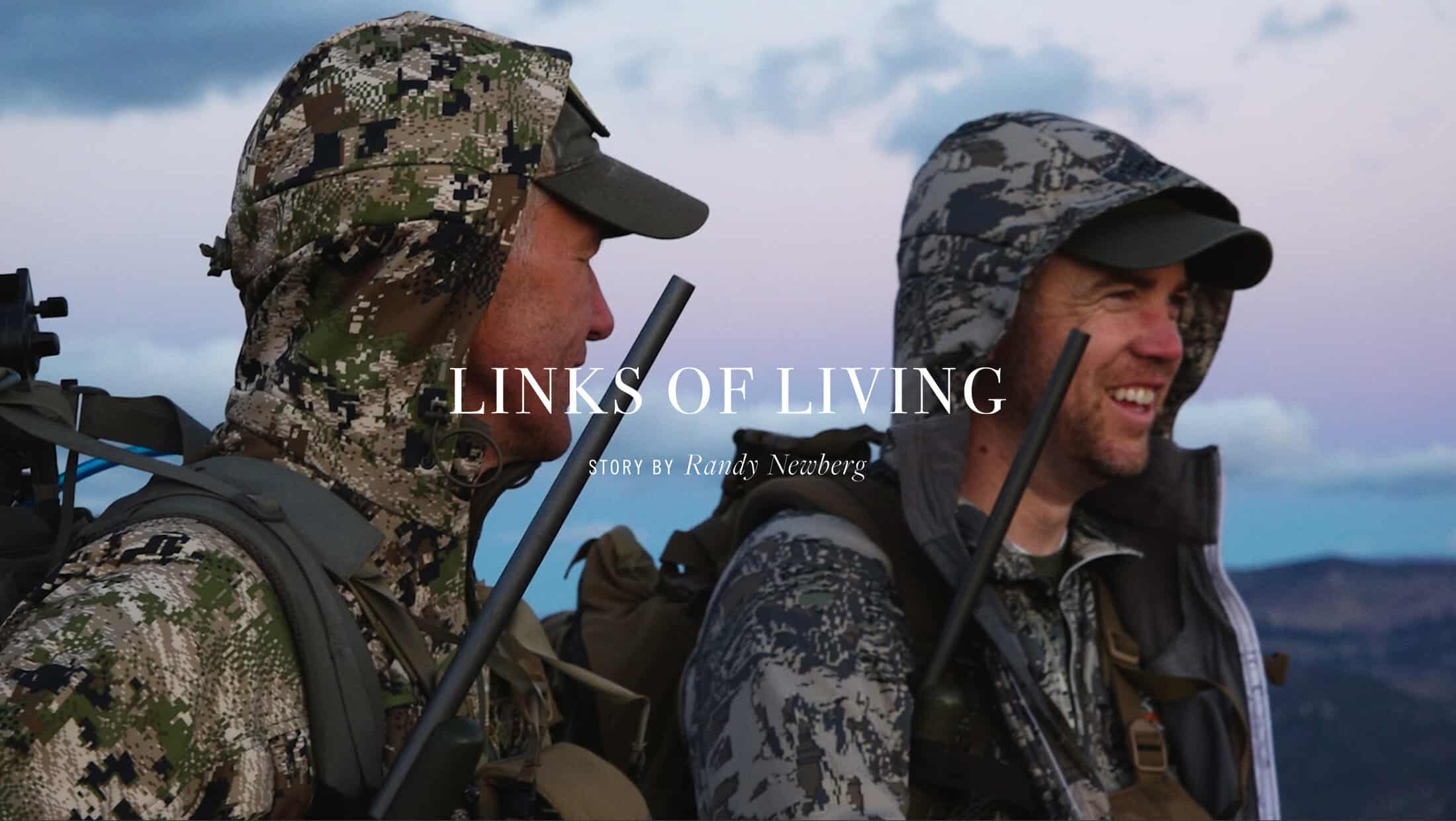

By measuring the joy I get from annual hunts with my own son, Matthew, I can see how Dad’s loss of traditions surely contributed to his struggles, his feeling of being adrift in an unfair world. Pondering the tragedy that was his life gives clarity to my blessings, my soul mostly unscarred by the blades of misfortune. I have avoided so many of the bad events of his life by my good luck, some discipline, and resistance to the temptations to which he succumbed. My eyes drift from his buck on the wall to mule deer pictures and framed limits of mallards, to Matthew’s elk mounted on the adjacent wall — a bull my brother helped us haul from the deepest part of the Missouri River Breaks — all links in a chain that locks me and my son to a shared life of annual camps in the mountains, dreaming of what might be, but mostly living for what is.

Related Stories

Latest Stories