Your cart is empty

The act of hunting itself stretches far beyond the bounds of our labeled identities. And yet, hunters who fall outside of the mainstream American status quo of “who a hunter is” experience barriers not of their own making.

Interview

Photos

Hunters of Color

Read Time

21 minutes

Posted

The next few pages hold a story further from the hunt and closer to the heart of what it means to be human. The act of hunting itself stretches far beyond the bounds of our labeled identities. And yet, hunters who fall outside of the mainstream American status quo of “who a hunter is” experience barriers not of their own making.

How does one learn to hunt, then, should they be curious about the endeavor?

Hunters of Color, a non-profit based in Corvallis, Oregon, aims to answer that question for people who identify as BIPOC, both within hunting ranks and beyond it. With goals of educating the public, fostering hunting mentorship for BIPOC individuals, and ultimately broadening the communal sense of urgency for matters involving wildlife and conservation, HOC is a light not only for the people it serves, but for hunters writ large.

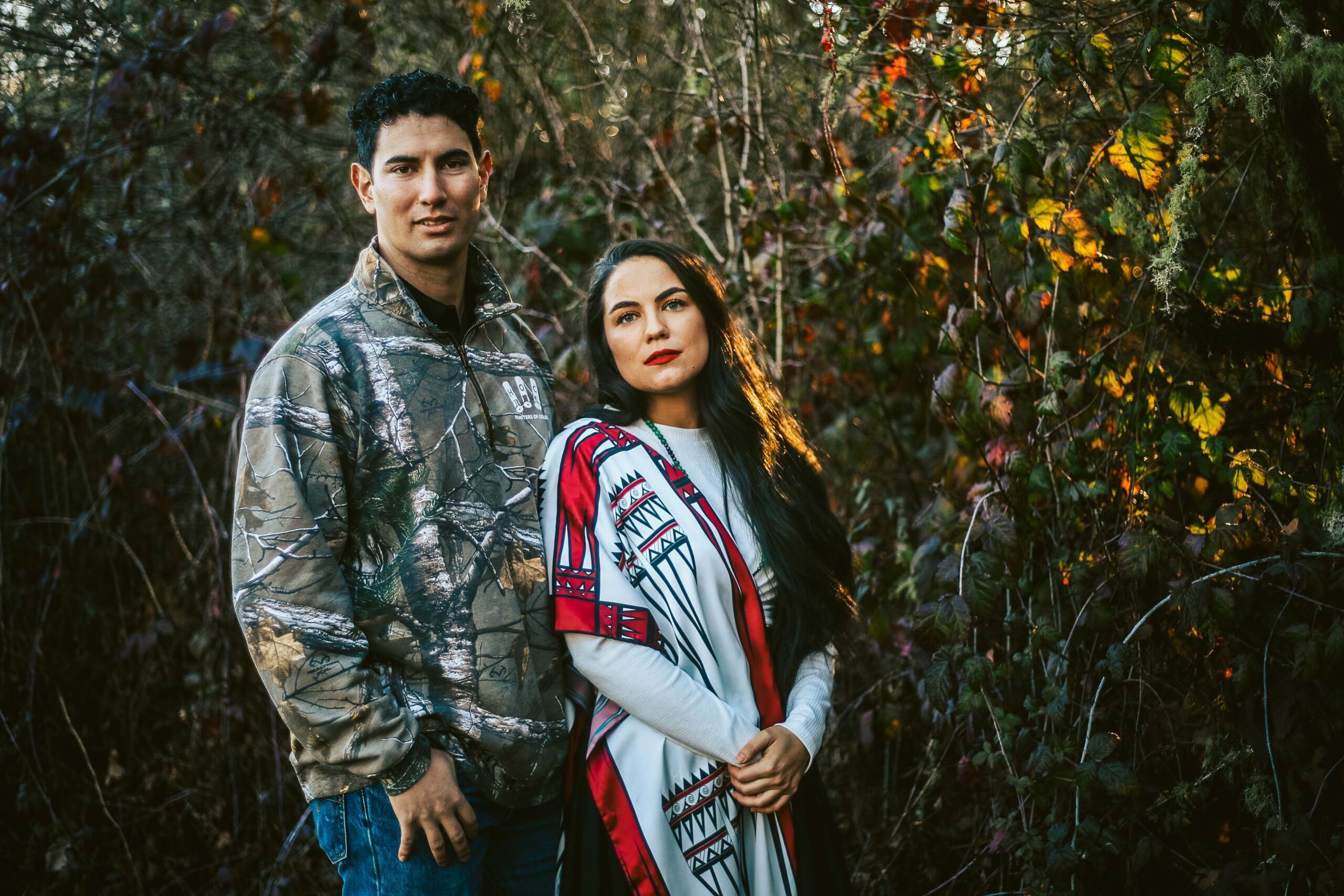

Modern Huntsman’s Editor-in-Chief Tyler Sharp chatted with co-founders Lydia Parker and Jimmy Flatt about HOC’s origin story, their own experiences as BIPOC hunters, and where we can all move forward to create a stronger, more unified and ultimately more welcoming community of hunters.

Presented By

TYLER SHARP — Tell us a little bit about yourselves and the experiences you had that contributed to the path you’re on now.

LYDIA PARKER — She:kon sewakwe:kon. (Translated: Greetings, everyone). My name is Lydia, and I am the executive director as well as one of the co-founders of Hunters of Color. I am from the Six Nations of the Grand River, Walker-Mohawk Band of the Kanien ‘keha:ka — or Mohawk Tribe as we’re more commonly known. For me, the path that we’re currently on — meaning running this nonprofit that helps other people of color get into hunting, conservation and the outdoors — started when I was little, with just an affinity for nature and for the outdoors. My parents have so many stories about me crying when new building complexes or neighborhoods were being put in wild places that I loved.

When I met Jimmy and Thomas [Tyner] — the two co-founders of Hunters of Color — I had never actually gone hunting. That was about five or six years ago, and they encouraged me to pursue that connection to my family heritage. My tribe is from the East Coast, and we’ve been hunting since time immemorial. Hunting opened my eyes to show me that all of us come from hunters at one point. None of us would be alive today if our families didn’t hunt. I’m a big statistics person. I have a degree in history, and so when I read the statistics about the lack of people of color in hunting — less than 4% of all hunters identify as people of color — it really broke my heart. This ties in directly to the connection to nature that I feel so strongly, the connection to my ancestors through the outdoors, as well as harvesting my own food and providing for my family. That doesn’t leave out the connection to conservation that hunting provides and the funding that hunting provides for conservation. I think these connections are really important for communities of color to be able to access, and I’m proud to be doing that now after my journey.

TS— How about you, Jimmy?

JIMMY FLATT — My name is Jimmy Flatt, and I am a hunter. I am the son of an immigrant woman and of a father whose family is from the Philippines and Hawaii. So, I come from a multicultural household. I was born and raised in the Bay Area of California, which is the second most diverse place in the nation. Growing up, I had observations of me and my dad being the only brown people hunting out there. And in 2016, those observations were backed with facts when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service came out with a demographic study that Lydia mentioned. What led me to where we’re at now is my passion for the outdoors and absolute love for it. It brought so much peace and belonging in my life that I wanted to show other people in the BIPOC community how to love something that provides for us and something we can tap into to feed ourselves. I want more of my community members to be engaged in the thing I love so much. This is why we incorporated the nonprofit and are actively getting people outdoors and falling in love with the resource.

TS — Tell me a little bit more about how you three met. What was the culmination that led to formalizing this mission?

JF — It started with the statistics coming out and me having this observation. Thomas is a college buddy of ours from Oregon State University, and he’s the only other hunter of color that I knew in school.

We were thinking about starting our own YouTube channel, as well as creating a for-profit shirt company that would have provocative statements on the back, the statistics or something like that. But then we realized that’s not going to actually get anything done; what really needed to happen was the formation of a nonprofit. And that’s where Lydia came in and pushed us over the edge, because we were just throwing around ideas for about three years.

Finally, Lydia said, “Stop saying you’re going to do something about it.” Lydia actually got the business license filed for nonprofit status. She did all of the legwork up front, and Thomas and I rolled with it. In 2020, we became a nonprofit, started to do some programming, and we got around 15 people out. Really, it was a passion project until the funding started to come in 2021. This year, we’re rapidly approaching over a thousand people we’ve got into the field.

TS — There are people who are going to read this who aren’t familiar with your organization or what you focus on. Can you give us the introduce-yourself-at-a-cocktail-party version and talk a little bit more about what your mission is?

LP — I always say, “Picture a hunter.” And oftentimes when I do that, people laugh and say, “Okay.” And then I ask, “Did you picture me?” And their answer is, “No.”

It’s not often that people would picture an Indigenous woman, which is really disappointing to me on this continent where my family and other Indigenous communities have been hunting for longer than most recorded history. So I always use that as an icebreaker, and I follow that up with asking who they pictured. “My Uncle John” or “My Grandpa Mike.” And it’s often just another observation that people have had where it’s someone in their family who’s hunted. They’re usually male-identifying. They’re usually older and identify as white or caucasian.

We saw that there were organizations helping women get into hunting, helping people with disabilities get into hunting, veterans, children. And then I saw this gap in the demographics and realized that we could also do something to help other communities that haven’t had the same opportunities or face different barriers get into hunting just like those other organizations do.

And so our vision is a hunting community that represents our diverse demographics as a nation.

JF — To add to that, our mission is to create accessible, equitable opportunities for BIPOC in conservation and hunting by dismantling barriers to entry through educational opportunities, mentorship and providing educational resources.

To distill that down further, we want folks to be so invested in hunting and conservation that they want to pursue careers paths in it, too. And so what we are essentially doing is creating pathways to the outdoors and career paths in the outdoors.

The best way to do that is to fall in love with the resource. And I think one of the most intimate connections you can have with nature is through hunting. When we go to conservation conferences, where all the large organizations are, we look around the room and we see very little tribal representation, and we see very little racial diversity. To me, it’s a shame, because our natural resources belong to everyone in this country and there’s a large chunk of us who don’t participate for whatever reason.

Hunters of Color works to break down all of those reasons and barriers, to dismantle the notion that the outdoors or hunting is a white sport or whatever it may be. And we want people to be making decisions and voting for the sake of hunting rights and wildlife management.

TS — What are some of the realities that hunters of color face out in the field that might make it difficult for them to pursue this path?

LP — The three main barriers that we identified for communities of color are lack of access to gear and land, lack of exposure, and lack of education and resources. We’ll talk about lack of access first, as I see that as the biggest issue.

According to the USDA, 98% of all land in the U.S. is owned by white Americans. Texas is a really good example of this lack of access. There’s not a lot of public land down there in comparison to where we are based here in Oregon and a lot of other states, and so that’s just a huge barrier in and of itself, right?

If you don’t own land, and if you aren’t friends with the folks who own land, then you’re going to have a harder time finding somewhere to hunt unless you have expendable capital to pay for access to private land. And again, statistics tell us that people of color, or BIPOC, own only 14% of the wealth in this country. Again, you have to look back at Indigenous removal from land.

Other exclusions include the denial of capital that would have afforded BIPOC people the ability to live in certain neighborhoods or buy tracts of land. Segregation and “redlining” — the discriminatory process of mortgage companies denying loans to people they believed would “lower” certain neighborhoods’ value — have all led to racial inequity in land ownership. The opportunity to build generational wealth ties deeply into land ownership and being able to work the land and make money from it. These are huge barriers for communities of color in particular as well as anyone who doesn’t have land access or the capital to pay for that access.

Secondly, many BIPOC people have had minimal, if any, exposure to hunting. Like I said earlier, if you don’t have folks around you who are hunting, it’s going to seem like some obscure thing that some people do somewhere; I’ve even seen comments on social media that say, “I didn’t realize that people still hunted.”

Many people think that hunting is this archaic thing if they haven’t had that exposure and if they don’t know any hunters. And, of course, if they don’t know about hunting, they also don’t know how and why hunting contributes to population management, to conservation, and to ecology in general.

Thirdly, the lack of education on how to hunt is an issue. Most of us learn how to hunt from our family or close friends. It’s only a recent thing — and it’s been a controversial thing in some cases — where people are learning to hunt through mentorship programs or through outside sources. This really means that new hunters often learn from complete strangers, through state agencies or organizations like ourselves.

If you don’t have friends or family who hunt, then not only are you not going to have exposure, but you’re also likely to have trouble finding someone to teach you. That’s why our mentorship program — which is active in 12 states now — is super important to communities of color.

We call our Hunters of Color communities “surrogate families.” They’re basically chapters, and these give people the opportunity to learn from a mother-figure, father-figure, or someone who has the experience in the outdoors that their actual family or friends might not.

One of the other barriers is clearly fear of prejudice or fear of entering a space or an activity that we’ve been told isn’t for us. And oftentimes, that comes from our own communities. We’re told, “Oh, you hunt? That’s not what we do,” or “that’s a white person thing to do.” And unfortunately, that’s a stereotype that is clearly wrong. Our motto is “The Outdoors Are for Everyone,” and that’s the truth and we’re sticking to it.

As a young Indigenous woman, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) are always on my mind. That, coupled with historical traumas regarding the treatment of Indigenous people on this land — forced removals, death marches, etc. — makes me see the outdoors in a different light. When entering rural spaces, if you’re the only person of color, or if you’re the only woman, it can be really intimidating. You never know who you’re going to face out there in the middle of nowhere with people who have firearms. Part of the Indigenous experience, and often the BIPOC experience as a whole, is being the only person of your ethnicity in the room — or in this case, at the hunt camp. You never know what they’re going to think about seeing someone like you out there, especially if they aren’t used to seeing someone like you out there.

So it can be really intimidating, and I’m sure it doesn’t take too much stretch of imagination for readers to recognize that.

JF — It’s important to add the lack of representation across the hunting media sphere. I do think that it’s getting better. Folks are starting to realize that representation is important. If you don’t see yourself represented, then why would you think that you belong doing that thing? Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente had a huge impact on baseball because of representation, so the importance of representation should not be overlooked. I’ll add that I do think there is more representation in the hunting industry, and it’s getting better all the time. Brands and publications are starting to highlight more hunters of color and folks who have defied the statistical odds and are actively doing it.

That’s something we’ve tried to do with our Feature Fridays on social media when we can. Each time, we feature a hunter of color around the nation who has defied the statistical odds and is actively participating in the thing that we love so much.

TS — What are some of the difficulties you have experienced? How did you handle those situations?

JF — I had a [formative and] traumatic experience in high school when my parents were just allowing me to hunt on my own or with friends for the first time without adult supervision. It was right after we got our driver’s licenses. I was trying to find friends to hunt with, because going out by yourself is a pretty daunting task. And so I found these two brothers who I thought would be welcoming, and they invited me out on a duck hunt. Instead, they were throwing racial slurs and making me feel extremely uncomfortable. It got physical, and needless to say, I didn’t hunt with them ever again.

That was an eye-opening moment. I realized I needed to find people I could trust, and I needed to find good-quality people to be around if I wanted to continue to hunt on my own. When I was with my dad, I never felt unsafe. I knew my dad would always protect me, but taking that leap into finding friends or even mentors to hunt with was pretty daunting.

I don’t want anybody to have to go through any traumatic experiences that may deter them from returning to hunting and continuing to be a part of the community, because it is such a rich wonderful spirited community. Looking back, a lot of my lived experiences shaped the development of our programs and the methodology for it to be successful and enlist a new hunter.

The other day, my mentee got his first pheasant; this was his first kill ever. He’s a goofy guy as it is, but he lit up like a little kid and couldn’t have been any more excited about it. Being able to see that joy and to pass on this thing that I’ve loved for so long brings me back to when I was a little kid. I learned how to hunt with my dad, who was my mentor. Just being able to do that for one individual this year fills my heart with joy.

Through our programming, we facilitate group mentorship opportunities, and then we let those one-on-one connections be facilitated on their own. In the future, we’d like for individuals to be able to pick their mentors.

LP — My dad didn’t grow up on the reservation, and I think that has a lot to do with the fact that I didn’t grow up hunting. He grew up in a city instead as an urban Native — shout out to the 71%! — and to this day he has never touched a firearm, let alone hunted with one. For my dad, guns were viewed as a weapon rather than a tool with a means to an end of procuring food for your family. And I think that that’s a really common experience for a lot of communities of color who have felt traumatized by gun violence. So I think one of the biggest things for me was having to overcome this fear passed down from my dad. Hunting wasn’t a part of my childhood. It skipped a generation. And as Jimmy always says, “If you don’t know how to swim, if you don’t know how to play an instrument, if you don’t know how to garden, you’re not going to be able to teach your kids those things.” The same goes for hunting.

And I’m really grateful for Jimmy and Thomas and others who encouraged me to get into archery hunting. They also helped me ease into using a shotgun and rifle.

Beyond even the community aspect, the planet needs us. Wildlife needs us. Conservation needs us all to be invested. And we always say, “We can’t turn everyone into a hunter.” We recognize that, but what we can do is ensure that the next generation of diverse Americans is conscientious of the fact that hunting is so integral to conservation.

The other thing I’ll add is that Jimmy didn’t go into too much detail about some of the racism that he experienced growing up, but it’s unfortunate how many times when Jimmy tells this story, people say, “Oh, yeah. I’ve heard that kind of thing before” or “Man, there’ve been so many times where I’ve had to bite my tongue in the duck blind because what someone next to me is saying is super inappropriate toward women or toward people of color.”

My response is always, “Don’t bite your tongue. If they’re making it awkward, you say, ‘Hey, actually there’s a reason there aren’t any women in the blind with us right now, and it’s because they don’t feel comfortable around this kind of language. You’re perpetuating harm.’” I think that’s the whole point of integrity, right? It’s how you treat people, how you talk about people, and how you stand up for people when they’re not around.

TS — I couldn’t agree more, and we’re here to support in any way we can. Let’s shift toward what the future holds for Hunters of Color and what the grand vision looks like. You touched on this a little bit, but what do you hope to accomplish through your work?

JF — Right now, we are focused on expanding our programming and hope to eventually have our own land. We will continue to advocate for public lands and access to those lands, but we have found that access to private land makes building up an individual’s confidence as a hunter that much easier.

One of the largest barriers we currently face in accomplishing our mission is access to private lands where we can host our events. Private lands allow us to be in a more controlled environment, which we have seen to be invaluable in the process of building a new hunter’s confidence afield.

Our five-year goal is to have active programming in 80% of the nation. And when we look toward our long-term goal, it’s important to note that we have until 2044, according to the census, when the nation will no longer be majority white. So, by 2044, we want to make hunting demographics represent the demographics of the nation.

LP —Until we see that representation, and until we see the access and barriers being broken down so hunters can represent the demographics of our nation, then HOC needs to exist. And so it truly is our goal to simply create equal access and equitable opportunities for communities of color.

Our goal is to be in every state. And right now, at almost four years in, we’re in 12 states. We’re well on our way. We just are always looking for support from folks like you, Tyler, and from people who are willing to teach other folks how to hunt and people who are forward thinking, both in considering the future of conservation and what it’s going to take for all of us to come together to protect the resources that we love.

TS — What would you say to someone who’s skeptical of or opposed to your mission?

LP — The first thing that comes to mind on this subject is an episode from the Bear Grease podcast hosted by Clay Newcomb, and it features Jonathan Wilkins of Black Duck Revival. Jonathan is super cool, and converted an old church in Arkansas into a duck lodge, and we were able to take some folks down there and hunt with him.

In that podcast, Clay Newcomb said, “There are going to be people who think that this topic is too difficult, too hard to talk about. And the fact of the matter is that we’re hunters; we do hard things. And if we weren’t tough and capable of doing hard things, we wouldn’t be able to be hunters. If every time you went out elk hunting on the Oregon Coast, it was flat and there was no brush and you could see for 500 meters, then it wouldn’t be hunting on the Oregon Coast. It wouldn’t be elk hunting. If you didn’t have to pack out hundreds of pounds of meat with your buddies, it wouldn’t be hunting. If you didn’t have to shiver in the freezing cold in your waders, it wouldn’t be hunting.”

As hunters, we need to look toward the end goals, which are continued funding for conservation, continued participation in the things that we love like hunting, and the need for everyone to be a part of that and to care. I hope that if there is any part of anyone reading who doesn’t appreciate the mission, that you can at least appreciate what the end goal will be if the outdoors are made truly for everyone. If we’re able to continue our hunting traditions from here until the end of days, what will that look like for conservation if Hunters of Color is able to succeed in our mission?

TS — If anyone reading this is interested in getting involved, how can people support your mission or contribute in a constructive way moving forward?

JF — The main way folks can get involved is by providing resources. Those resources could be time or financial resources. If you believe in the mission and you want to back what we’re doing and/or sponsor a new hunter to get out, there are online portals to donate. If you want to be a mentor, there are applications for our state communities where you can get on the email list for whenever an event pops up. As long as you’ve done the racial sensitivity training, you’ll be qualified to come out, be a mentor and help facilitate those group mentorship opportunities.

LP — Of course we need buy-in from individuals, but we’re just as passionate about getting buy-in from companies and organizations. So we’re super grateful for you, Tyler, and folks from Modern Huntsman for taking time for this interview. We’re also grateful to Mystery Ranch for supporting this story and our big game mountaineering hunt program that’s coming up here soon in the state of Washington. It’s an honor to see companies buying in and giving of themselves to support our mission. It’s really humbling and exciting.

Again, we’re hunters. We do hard things, so strap up your boots. We can do this together, but we really need people to buy in. Even if you don’t care about our mission, and even if it doesn’t sit well with you when we say, “The outdoors are for everyone,” our hope is that people can look past their own discomfort to build a better future for conservation.

To learn more about Hunters of Color, get involved in mentorship or provide financial support through donations, you can find them on the following channels:

Website: www.huntersofcolor.org

Instagram: @huntersofcolor

Related Stories

Latest Stories