It was a revealing confession, a display of appreciation not for the high-scoring Boone and Crockett buck but for nature’s subtleties, and evidence of a philosophy borne of countless hours spent listening to the whisper of wind through the pines on a dewy morning.

Dan’s revelation was one of many rich character moments I discovered during a conversation at his lodge outside of Birmingham, AL, where he had retreated after guiding customers on a deer hunt in Texas. His “hello” was warm, the drawl of a Southern gentleman who is earnestly received at any dinner table, campfire or boardroom. I could tell he was beaming as he eagerly recounted the details of the hunt, and he admitted how he now almost prefers guiding over pulling the trigger himself. Conversation flowed easily. As we bounced from stories of his past accomplishments to mentors and dear friends, to the outdoors and wildlife, a portrait emerged of a man steeped with enduring, unwavering values. Honesty, integrity, confidence, empathy, optimism. A natural leader and honorable friend. It quickly became clear that he would live up to his legend, built not by self-preservation, but hard work, prudence and a healthy measure of good hunting.

A man of many good deeds, he’ll be the last to boast about them. This humility is somewhat at odds with the Dan Moultrie in front of a camera marketing a new deer feeder, the Dan Moultrie sitting proudly beside a lifetime buck, or the Dan Moultrie who has appeared on television shows with legendary football coaches or outdoor celebrities. In our conversations, I came to realize that fame was a byproduct of his insatiable drive to build. A means to an end. He wanted to build Moultrie into the best company it could be. He sought to forge genuine relationships and trust with individuals who shared his passion for living, and he worked tirelessly to build a brighter future for Alabamans, all while preserving his own personal relationship with natural resources that can be easy to exploit, yet difficult to preserve. Dan Moultrie is one of us, a bonafide outdoorsman whose legacy is only continuing to grow, and whose influence will span generations.

Following his graduation from Auburn University, Dan and his peers had a fresh perspective, and with that took a different approach to the outdoors than their fathers — one of leisure and curiosity. Moultrie was officially founded in 1979 after the results of his first automatic dispensing feeder were enough to convince his friends that they also needed one, then friends of friends, and so on. Emboldened by the demand for the feeders, he built a prototype for a camera with a tripwire-activated shutter that could be left in the woods in its protective housing to monitor deer activity — as long as the hunter developed the 35mm film in a timely manner. These two products established Moultrie as the pioneer and leader in wild game management, a burgeoning industry that entertained the exciting and rare possibility of blending business with pleasure.

Dan embraced the challenge of growth and was ripe for personal development. In particular, he was primed for a mentor. Through family connections and his status as an Auburn alumnus, he was introduced to Pat Dye, the legendary and highly respected head football coach at his alma mater. In the kingdom of football, Coach Dye was royalty. Known for his commitment to players and for his savvy ability to command excellence through discipline, his leadership during the ’80s and early ’90s created a dynasty that established the university as a powerhouse of the South and instilled a new sense of pride in everyone who called themselves a Tiger. So, when Dye joined Dan to help promote Moultrie after his coaching career, it was the ultimate endorsement.

The teachings of Coach Dye became essential as Dan navigated the next stage of Moultrie: expansion. In the late 1990s, advances in digital photography were making it easier and more affordable for consumers to take pictures without the hassle of developing film. The world was teetering on the edge of a technological revolution, and Dan recognized it. He knew that it was a golden opportunity to, once again, capture innovation and usher in a new era for Moultrie trail cameras. However, it soon became clear that such major technological innovation could easily drain the company’s resources, as early models required significant battery power, and cameras had to be adapted to the application of on-demand, triggered photography — a serious engineering challenge. For Moultrie to evolve, Dan decided it was time for help.

EBSCO owned a variety of other outdoor brands. At that point, Moultrie had been in business for over 20 years. Dan had proven his model and established his guiding principles of trust and strong relationships. He was prepared for the negotiation with then-president Jim Stephens, and guarded against the prospect that an acquisition would deviate from Moultrie ideals. “He and I went down to my old lodge and sat there and went through the whole deal several times. He said, ‘Have comfort in that we’ve never sold a hunting business, especially one like yours.’ And that appealed to me. You want to preserve that product line and what we built, that’s an awfully good way to do it.”

Moultrie formally became part of EBSCO in 2003 and fulfilled Dan’s ambition for new heights without sacrificing the heart of the company. Though he relinquished the helm, he remained an adviser and spokesman for Moultrie, a testament to the vision that he and Stephens had drawn together. It was a fresh start, a time to reflect. Dan understood that without the outdoors, without wild things, his life would have been completely different. He felt a call to serve the deer that appeared at his feeders, to secure the opportunity for the heart of a young hunter to skip when a mature buck seemingly materializes from thin air. He wanted to give back. That same year, he sought a volunteer position on the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Advisory Board, and he would ultimately shift the trajectory of game management in the state.

“At that time, it was estimated 85% of the bucks that were shot were a year and a half old,” Dan explained, signifying a population curve skewed to younger individuals and fewer animals reaching older ages. A big buck was rare. With the backing of wildlife biology, precedent from neighboring states and political support, Dan hoped to change that.

If the board were to recommend changing the law, he knew it was critical to have the support of the scientific community. One of the experts tapped for the initiative was Steve Ditchkoff, who was at the time an associate professor of wildlife at Auburn University. In 2007, he was quoted in The Birmingham News saying, “More mature bucks will suppress the breeding of younger bucks. It will reduce the length of the breeding season, and that will allow young deer to be in better condition and have better antler growth.” Ditchkoff also explained that Tennessee, which shares its southern border with Alabama, had already instituted a lower limit and was seeing positive results by the measure of older animals with larger, more developed antlers. Ambitiously, Dan and the board campaigned heavily to follow Tennsesee’s lead and effectively reduce the limit from 117 bucks in a season to a mere two.

The governor paused for a moment.“I gotta have one more.”

Dan was prepared to hold his ground. In the beginning, he had even considered a push for one buck. Based on research, they knew that the limit reduction was imperative for the health of Alabama’s deer herd, and it was a worthwhile battle. Their entire effort possibly hinged on the outcome of that meeting. However, over the years, he’d also learned that compromise was sometimes key to building the enduring relationships that he cherished. He and the commissioner accepted Governor Riley’s request and added a third buck to the proposal, so long as it had four points on one side or bigger.

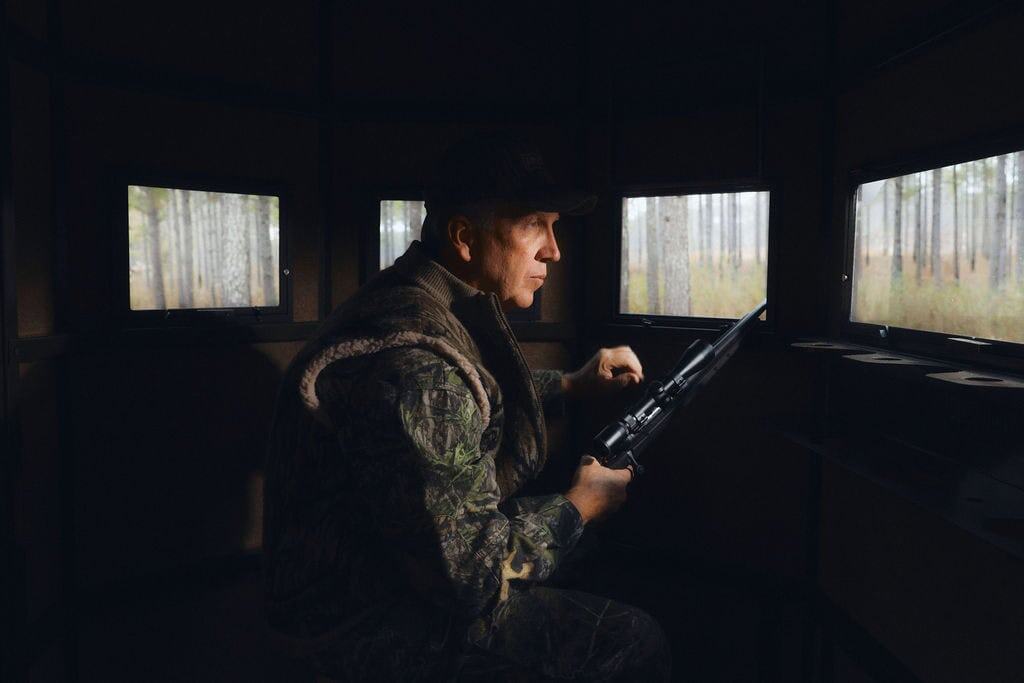

Dan’s time with the advisory board is just one feather in a hat that seems full of them from an illustrious career. His accomplishments in business and public life could easily be flaunted as trophies of achievement, gilded symbols of success for all to see and envy. It could be easy for him, as the empire was built with each camera and feeder feverishly stamped with his name. He could take credit for everything instead of acknowledging the friends and relationships he made along the way. Yet Dan still humbly reaches for his favorite Auburn ball cap, or maybe dons a well-worn Moultrie hat for an afternoon afield.

“Maybe we don’t need to stress about the heavy bag,” he contemplated. “I enjoy turkey hunting. Especially at this stage in life, it may be my favorite hunting that’s out there. When you’re calling that turkey and he’s talking back and forth, gobbling, strutting and putting on the show, then leaving when there’s a problem; there is so much communication. When you take the turkey, the show’s over. Boy, a lot of times it makes you wanna say, ‘Why kill him? We can do this more tomorrow if we don’t kill him.’” It’s a feeling he cherishes.