Your cart is empty

Despite the drumbeats of doom and gloom, there are many reasons to be optimistic about hunting’s future.

In a world where hunting is often misunderstood and frequently criticized, it is easy to become overwhelmed. Bombarded by a stream of sensational representations of hunting’s true nature and conservation influence, we cannot help but sometimes wonder where all this is headed. So we ask ourselves how many more challenges must we face; how many more false statements must we counter? How will we ever make our critics understand? How can we deal with those who are ideologically opposed to hunting and the use of animals under any circumstances — those who will never even try to understand? Are we to be like Sisyphus, constantly pushing our arguments before us but never cresting to a plateau where a shared understanding of hunting’s value is reached? Who in the hunting world does not ask themselves these questions?

It is only natural that we should worry about hunting’s future. After all, it is of great importance to us personally, and we know full well its conservation value. To lose hunting would be a matter of significance to wildlife, human cultures and economies. Furthermore, focusing on our challenges is a logical response. We want to fight back, provide counterarguments, and safeguard this tradition, and we feel frustrated that others do not see the conservation and societal value of what we do. How can this be when, to us, the evidence is so overwhelming? Yes, we spend a great deal of time wondering what the future holds for hunting and wildlife. And so we should. Like conservation itself, hunting’s future will be no accident; it will be secured by the actions we take, the commitments we make.

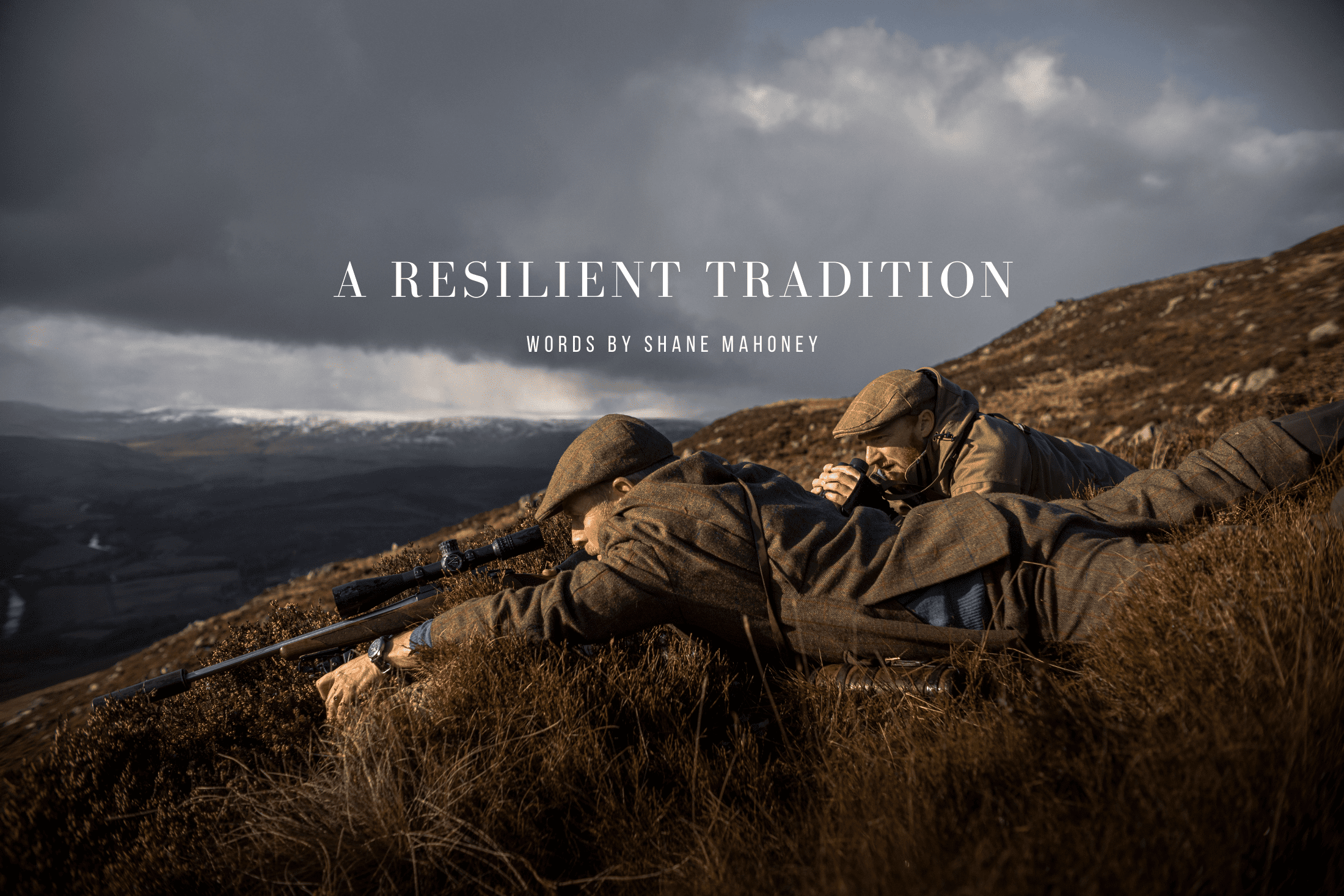

At the same time, however, we need to reflect on just how remarkable a force hunting remains in modern society. It is hardly a weakling on the verge of demise. On the contrary, it is a robust and resilient force in the lives of tens of millions worldwide. It’s held close, with intense conviction and purpose, and that leads to activism and a defense of the sacred. Hunting’s legacy runs deep, and its appeal and relevance radiate across a widening spectrum of society, attracting more women, urban residents, and people of different nationalities and cultures. Its repositioning, as a healthy and environmentally friendly food procurement system, can and will encourage a new wave of interest in the activity. There are many reasons to be optimistic about hunting’s future. Hunting is not going away.

Indeed, even for those of us who have been part of the hunting world, the scale and vibrancy of the activity worldwide is incredible. True, the screaming anti-hunting headlines and frenzied fringes of social media do sometimes capture the public’s attention. However, beneath these episodic squeals of outrage rolls a quieter thunder, a deep resonance of the citizen multitudes, who on landscapes as diverse as savannas, rainforests, and glacier-fed mountain valleys pursue the hunting tradition of their forebears, passing it on to their children and grandchildren. Sharing the wild meat they capture, hunters convey to a wider gathering the ecological appropriateness of taking responsibility for animal death, an inevitable consequence of the global food web that links humanity to the consumption of wild, living resources of all kinds.

There is no escaping the great universal truth that flesh eats flesh. We will either consume it literally through our fisheries, livestock raising, and hunting, or less directly by displacing the wild others of this planet to make room for fruit and crop production. As current international trends indicate, meat consumption is rising globally. So, while some might wish to eliminate hunting, this will certainly not eliminate animal death by human hands. Perhaps, to the critics of hunting, we might say, Choose your poison: Let animals live wild lives and die quick deaths, or live lives of confinement and domestication, and die just the same. For me, the choice is clear. As far as humanly possible, let them live wild and die wild, participating like us in the ritual of existence. Hunting mirrors our true human ecology; often as predator and sometimes as prey. Our dentition and our physiology indicate where we came from and will dictate what we seek. Meat will be high on our list.

Hunting is no sideshow. It will not be driven to the darkened corners of irrelevance by ridiculous claims that it is frivolous and without social or conservation value. No matter how shrill the protestations, hunting will stand firm. You might hear the call to stop all hunting, but let’s hear the plans to replace its conservation support and practical services to society. Tell us what will replace it. Give us the blueprint for sustained economic and political support for wildlife conservation, should hunting disappear. Please, tell us who will pay the bills. Who will pay for nuisance black bear removals, the counting of animal populations, the habitat recovery and restoration programs, the wildlife disease research, the anti-poaching and enforcement efforts, to name just a few of the issues that in North America and elsewhere are significantly, or entirely, supported by hunters’ dollars? The social, economic, and conservation benefits of hunting are manifest. What is the alternative model that will provide the equivalent support over the vast jurisdictions where hunting is presently so critically important?

Blind faith and empty rhetoric are not enough, not when the future of wildlife is at stake. How will wildlife be cared for and managed? Why would citizens who have little, or fleeting engagement with wild animals, willingly pay for their protection and management? Who will manage the superabundant species, the threatening and dangerous carnivores, the disease agents passed between wildlife and humans?

These, of course, are practical questions. There are also more philosophical ones: Who has the right to take away the legal harvest of wildlife by individuals for their own sustenance and well-being, while industries are encouraged, and often subsidized, to harvest fishes and domestic animals by the billions for food and profit? Further, in a world altered massively by human commerce and abundance, wildlife will not be sustained without human agencies to counterbalance these potentially destructive forces. We need every community that can and is willing to support wildlife to be in the conservation game. Hunters are, indisputably, one of the most enduring and effective of these communities. Why would anyone concerned with wildlife conservation want to eliminate any pro-wildlife force?

Despite its critics, hunting is not going to disappear, and there are many reasons to believe that it will not just survive, but thrive, into the future. Nowhere is this more true than in Canada and the United States, two countries that have embedded hunting within the fabrics of their society and within their wildlife conservation system —a shared bi-national approach often referred to as the North American Model. It is recognized as one of the most successful wildlife conservation systems on the planet, having rescued wildlife in the late 19th and 20th centuries, and brought it to incredible 21st-century abundance. Look at the deer in our gardens, the black bears in our communities, the turkeys in our driveways, and the geese on our lawns — does anyone really believe this is a beautiful accident? Who made this happen? Who invested most and why?

For over a century now, hunting has been at the heart of conservation in our countries, and in others around the world. Its social relevance and resilience have been maintained over that long stretch of time, despite the enormous changes that have occurred in our communities, societies, and natural landscapes. This is the headline we need to focus on. What has sustained hunting is the passionate commitment individual hunters have to their tradition and their willingness to give back. This is not going to change.

Hunting remains vibrant in the lives of tens of millions of citizens and thousands of communities. Its impacts on conservation and the economy are enormous and without parallel in North American society. Wildlife cannot afford to lose it. Neither can we. And we won’t anytime soon.

Related Stories

Latest Stories