Your cart is empty

WORDS BY Katie Marchetti

PHOTOS BY Rick Hutton

PENNSYLVANIA | CAMP NO. 7-C-38

At the turn of the 20th century, the northern tier of the state of Pennsylvania was clear-cut by loggers. When the logging industry moved west, huge swaths of acreage were left devoid of industry and wild game. The state Bureau of Forestry purchased the land in an effort to reforest what had become known as the “Pennsylvania Desert.”

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania began establishing national forests, spearheading conservation, and the concept of public land use. Land was being set aside to be enjoyed by the public, and by 1913, land could even be leased. Pick a spot and apply, the legislature said. A privately-owned quarter-acre lot of public land could be yours with a 99-year lease, where you could build a camp for generations to enjoy.

In 1918, soldiers returned home to a changed world. Beneath the foreign weight of civilian life, surrounded by family and friends, in suits instead of combat boots, they found their reprieve from the Great War in the camaraderie of men at arms. When hunting season dawned, they shouldered rifles once again and stepped off the grid — a pilgrimage to cabins leased on public land, or family-owned pieces of northern Pennsylvania woods.

Hunting deer and bears in the remote forest offered a reprieve from the memories of overseas, and collars of routine back-breaking work, and families to feed in Pennsylvania’s southern cities.

In their absence, clear-cut acres had flourished into an early successional habitat. A young forest with browse, food, cover, low predation, and minimal hunting pressure caused the deer herd to explode. But the depression of the 1930s swept many northern farms to state-owned public land, and World War ll would again take hunters overseas.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt stepped onto the scene with his able-bodied institution of the Civilian Conservation Corps, and state-leased camps grew in number from 30 to 3,180. Roosevelt made outdoor recreation readily accessible to the people; setting the stage for the Pennsylvania deer camp culture that is still ingrained today.

By the late 1940s, the returning heroes would retrace their steps to the cabins of their youth for two weeks each fall. Bedecked in “Pennsylvania Tuxedos” — plaids of black and white from the town of Woolrich — they made their pilgrimages north to a primitive place.

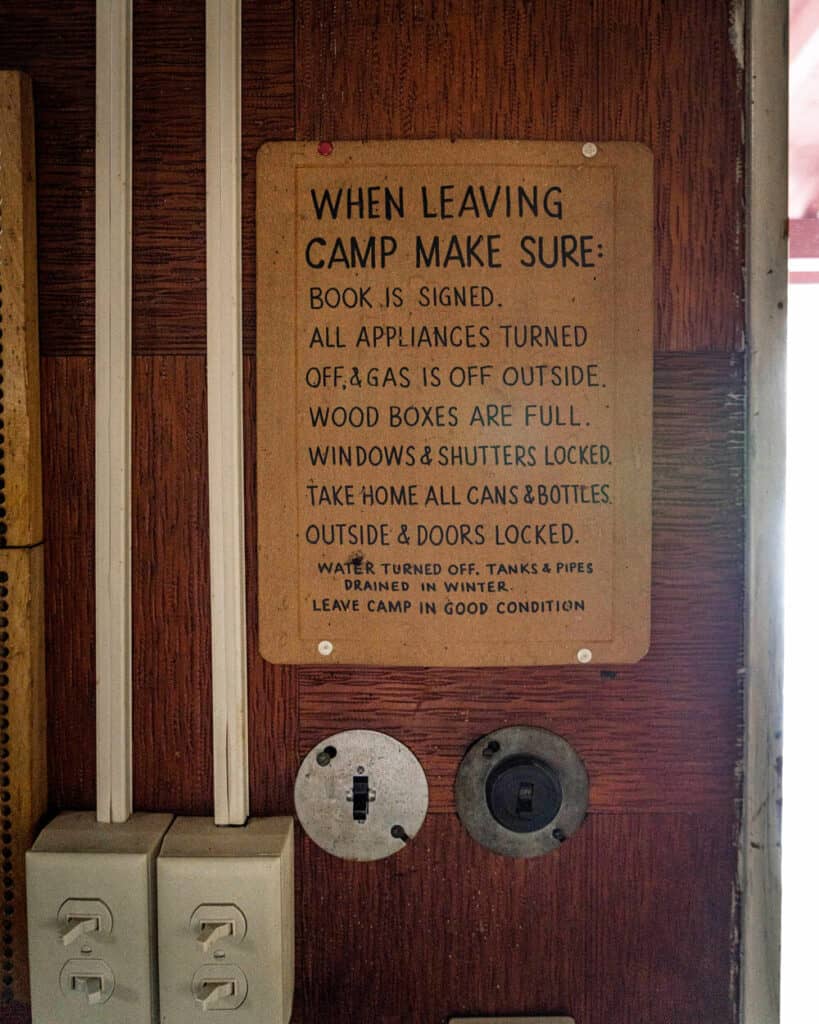

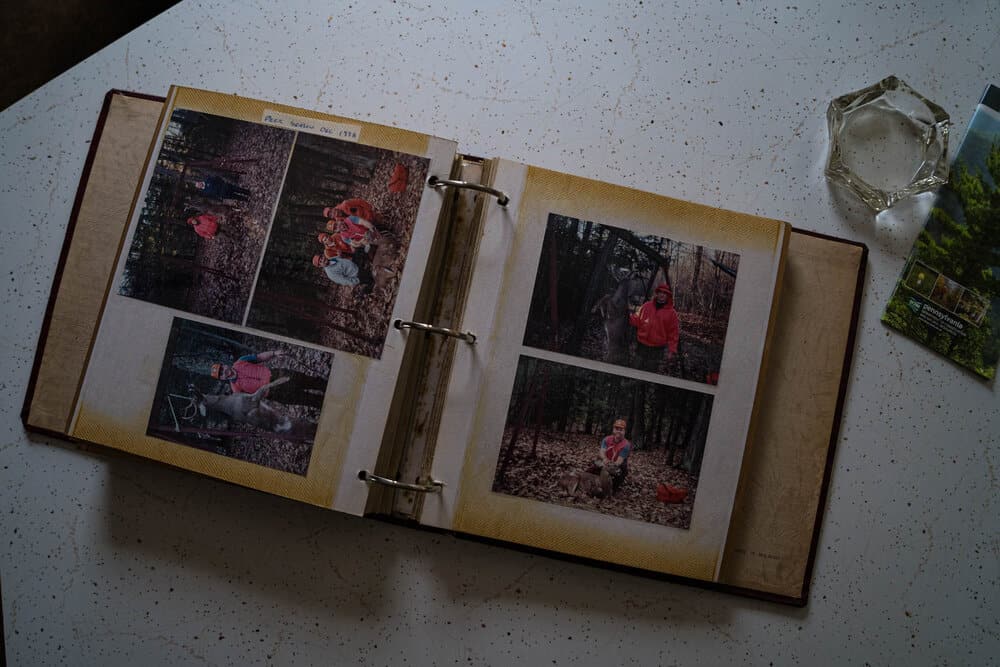

A roster hung by the cabin door, and military bunks began to line the walls. Army-issued canteens were filled, dinner plates from navy ships littered the table, and Polaroid pictures of men in blaze orange decorated the walls. The American flag sat above the fireplace, and a framed picture of the president rested on the mantle regardless of the face — the heritage of deer camp was being written on their souls.

In the field, they worked as a unit. With matching strides, they pushed deer and bear to the waiting rifleman, a ‘run and gun’ style of hunting seldom seen west of the Mississippi. The animals would later hang from frames in front of the cabin, the men making quick work of skinning and butchering before dark, turning animals into food for those eagerly anticipating their triumphant return back home.

They drank, smoked and talked late into the night with flickering flames dancing across their wool-clad shoulders — away from it all and more connected than before.

For Rick Hutton, this was the definition of hunting. The jostle of riding in a truck bed to the mountains ahead, held in place by the rough hands of the coal miners from which he grew. En route to the Antler Hunting Club deer camp, to find his future and history fortified under a single, primitive roof.

The Antler Hunting Club was erected at the head of Furnace Run Gap in Bald Eagle State Forest on the Union/Snyder county border in Pennsylvania in 1926. It was composed of 20 Pennsylvania Dutchmen from a two-county area in the southeast; each man paid a $1 entrance fee, and an additional $50 was put toward the construction of the cabin. Rick followed his grandfathers’, uncles’, and father’s lead 86 years later when he was voted in as a third-generation member in 2012.

“I have been hunting there since I was a kid,” says Rick. “My dad didn’t let me go to camp my first year, when I was 12, because driven hunting is very tough and the guys expect everyone to keep up.” Climbing incredibly steep hills covered in thick rhododendron and mountain laurel was too much for a kid, so his first whitetail was shot from beneath a tree, sitting next to his Dad.

Rick’s dad deployed to Iraq that year, and so it was Uncle Ralph who made the introduction to deer camp. At 13 years old, Rick loaded his father’s flintlock rifle and followed a group of strangers into the woods. Traversing the backwoods of Pennsylvania, his ears burned from the unfiltered adult conversation, head spinning from the older men’s arguments about the day’s deer-driving plan.

“I was nervous; it’s a lot of pressure when you’re a 12- or 13-year-old kid. You have to walk through the woods, stay in line with guys that you can’t see most of the time who are yelling and hooting. You’re shooting fast, you’re reloading fast,” explained Rick. “But they were a very well-oiled team, and they pushed a lot of ground very efficiently. That’s the drive hunting culture.”

Coordination is key in deer drives when you’re racing daylight to ‘push’ country while maintaining narrow gaps that discourage the deer from doubling back. Men are split into two groups — drivers and posters, or chasers and watchers, terminology dependent on your camp. The posters/watchers line up, still and quiet, waiting for the driver/chasers to push the deer toward them.

When done correctly, the hours move with military precision, a deer pushed and a deer shot, each man fulfilling his mission for the day.

The armed forces have left many generational marks on the foundation of deer camp. From tools to technology, assigned tasks to working as a team, the traditions established here at home were shaped half a world away.

“Modern hunting technology was forged by the military,” explains Rick. “In 1906 they came out with the 30-06 rifle cartridge for the military, which has now killed a lot of wild game in North America, and countless gun cases in America hold one today. Wool clothing and camouflage started as military technology, and boot technological advances from World War II went into improved hunting boots.”

According to Rick, his camp is littered with wartime memorabilia, tools given a second life when they were transported to deer camp. U.S. Military surplus army bunks and packs that once carried soldiers’ rations now hold the hunter’s essentials.

“Pennsylvania has great-grandsons that are now hunting in the same camps and sleeping in the same bunks that their great-grandfathers did,” Rick says with enthusiasm. “Modern hunting culture was steeped by the world wars; the greatest generation coming back forged that camp tradition of camaraderie and working together for a goal. I love that; I’m very nostalgic toward that time in our history.”

Hunting camp holds not only military history, but also significant family history for Rick. His grandfather Ralph, a long-time Bell Telephone Company employee and Korean War veteran, passed away at their hunting cabin on the opening day of deer season in 1988. After the morning drive, his grandfather returned to camp for lunch, where a heart attack took his life at the kitchen table.

As older generations inevitably pass on, the culture of deer driving has ebbed and flowed as well. Rick refers to the ‘80s and ‘90s as the “good old days of deer drives.” Since then, social pressure, wildlife management, and habit alterations have made a serious impact on deer camp culture. Hunting in Pennsylvania today has begun to shift from drives to deer stands.

“Driving culture is really fun. It’s fast-paced; you’re not sitting and freezing. But you lose something found in a tree stand,” he explains. “Moments bow hunting, stand hunting, listening to acorns fall through the trees, leaves rustling in the breeze as you watch nature wake up, are my favorite. You watch things unfold at a natural pace versus in a drive hunting environment where you’re controlling the pace.

Rick continues, “The older I got, the more I watched television and read hunting magazines and realized they weren’t writing about deer drives. I felt the burden of taking bad shots at a lot of running deer when I was younger. I didn’t want to kill just any buck anymore, I wanted to try to find a nice one.”

In college, while pursuing a forestry degree from Penn State, he gravitated toward bow hunting whitetails from a tree stand, returning to camp life for bear drives only, which became the common direction for camps in the North.

“Almost every one of my friends at college had a camp,” says Rick. Camps varied from those that acted as a second home with running water and TV, to crude shelters with outhouses requiring fresh water to be hauled in by hand — on both public and private land all over the state. “It was interesting to hear stories and talk about camp. Everyone wanted to know how your camp was set up; it’s such a part of our state history.”

The United States is a crosspatch of hunting cultures, divided by the breadbasket states. Rick headed west after college, leaving deer drives behind on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains. He fully embraced the hunting traditions of the West — spot and stalk pursuits across the open landscape of Montana. The traditions of his youth are illegal in his new home state.

“For Rick, a well-rounded outdoorsman should know how to set up a drive, as well as be able to undertake the spot and stalk methods he utilizes today. He credits a great deal of his knowledge of hunting to what he learned about habitat and animal behavior by moving animals across a landscape in his youth. ”

Mule deer and whitetail are held in equal esteem for Rick, as are bows and rifles, drives, tree stands, and spot and stalk methods.

“I love the West,” he says. “I also miss Pennsylvania deer hunting heritage and culture,” he adds, remembering school being closed on the first day of rifle season in a state that in 2013 could boast 13.1 hunters per square mile. “It was crazy how many guys were in the woods hunting. I don’t miss the hunting pressure of a sea of orange on opening day or it sounding like there’s a war, but I do miss the camp camaraderie and that hard oak–hickory hardwood landscape. That’s my heritage.”

He hopes to one day pass both cherished traditions on to the next generation — the Western tradition of a wall tent camp while hunting elk in the mountains, as well as hunting whitetails in Eastern deciduous forests.

Like many men and women from Pennsylvania, Rick was shaped by the log cabins of his youth. Although traditions have changed day by day, and modern technology has reached even these remote sanctuaries, hunters still follow the familiar pilgrimages of their grandfathers into the mountains. They search for a glimpse of a whitetail bounding through the northern woods, carrying the same gun that weighed heavy in generations of calloused hands, to find each step on the well-worn path consecrated by a history of hunters in the Pennsylvania hardwoods.