Your cart is empty

Story by

Photos

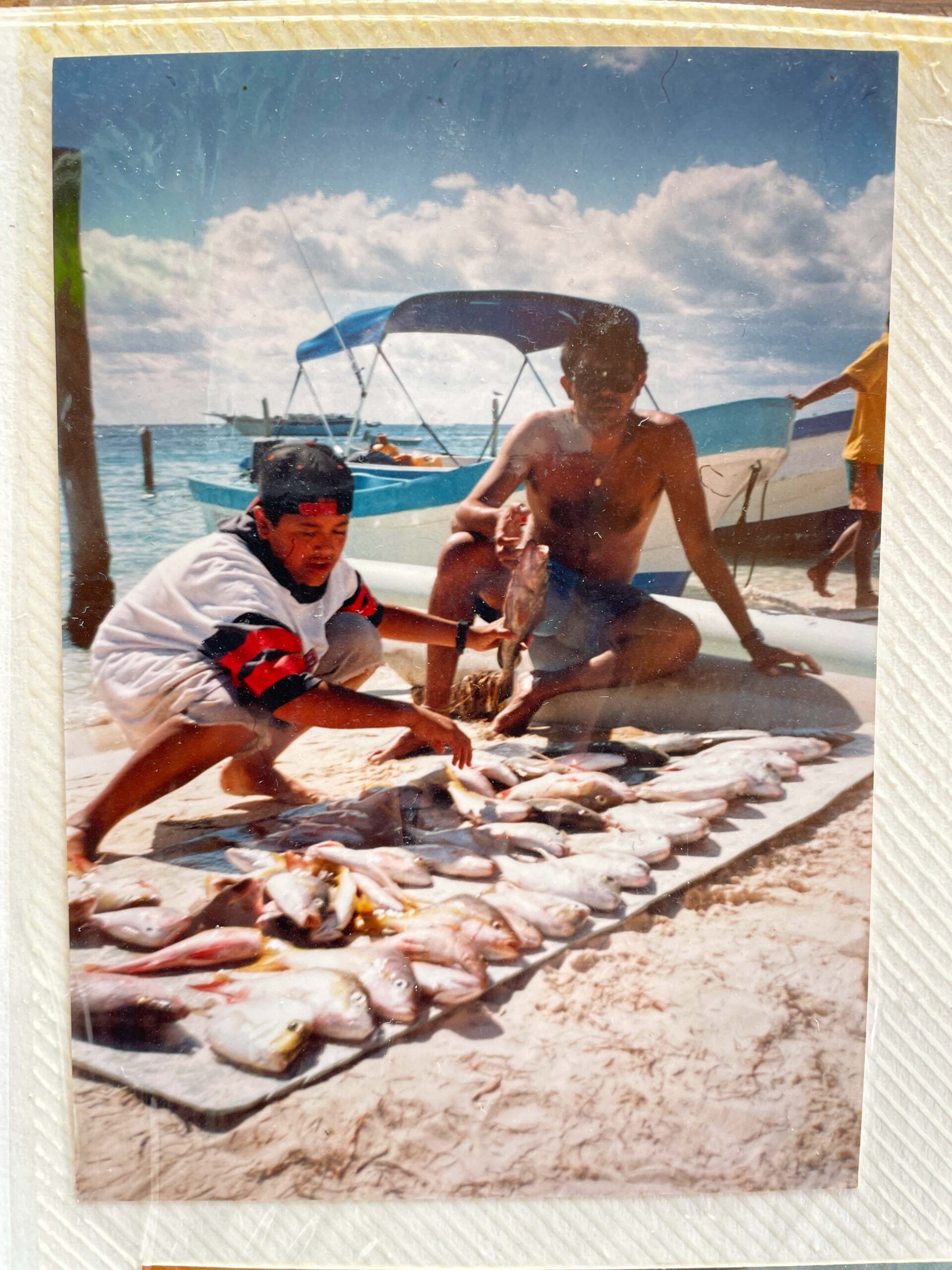

Chef Eduardo Garcia

Read Time

20 minutes

Posted

It’s early. Before the sun rises. Before the rooster crows. In darkness, I walk the familiar path through the house to the kitchen. Lights on, burner lit. As the kettle warms, I slip into the shower. I carefully choose the clothes that will be my uniform for whatever chores the day ahead brings. The work changes with the seasons, but one thing remains constant — the day starts early here on the farm. I find ritual in these early mornings and space for my busy mind to wander.

At the kitchen table a hot cup of coffee warms my hand. A spoon swirled through a bowl of oats readied for breakfast stirs something inside, and my thoughts begin to drift back down a well-worn path. I am thinking about food, again.

Although my whole life focuses on food, on what I grow, create and share, rarely does that mean I am obsessing over when or how I eat, or over technique, ingenuity or skill. Sure, sometimes, but for the most part, my obsession with food is actually in how it builds my relationships with people and places.

How does one become obsessed with food? I suppose it’s in the influences of nature and nurture. Maybe it starts as far back as conception — elements of food and drink mixing in with the chemical cocktail that catalyzes you into existence. Obsession grows in moments of impact and influence. It’s seasoned by facts and figures. Memories of scent, taste and feel mix and blend with stories and act as waypoints on a timeline, sketched on a piece of butcher paper rolled out across a grand harvest table. All the ingredients are there, and I can’t help but feast. Starting at one end, at this early morning breakfast at a table, on a farm, I trace the timeline back through my life.

Van Nuys, Los Angeles County, California, 1983

I remember the fruit trees in our backyard — apricots, to be exact. I remember the beach and the smell of salt. My bare feet walking on sidewalks hot enough to fry an egg: the feel of summer. And I remember oatmeal. It’s what I recall as my first complete meal.

Somewhere in my mind there is a photo. Mom, ever graceful, appears to have one leg stretched backward toward the stove while leaning forward in the opposite direction, arms outstretched in a committed lunge. She looks like a dancer. She’s performing the dance of a single mom trying to keep one, if not both, of her boys from dumping breakfast onto the floor. My twin brother Eugenio and I are three years old. Our creased, swinging legs attempt to anchor squirming derrières to our highchairs as we adventure through breakfast: a warm bowl of cooked oats. Do I remember my brother and I wearing our bowls as hats and rubbing oats all over our faces? No, I do not. But there is a photo somewhere that serves as proof.

In my memory, those oats always tasted a little burnt, but maybe they just looked dark. The story I have pinned to that recollection was that Mom was busy. And so naturally, things happened. Food burned. What I later learned was that Mom had been told by a fellow mother that toasting oats coaxed a deeper, more complex flavor from the grains: a small added step in the process because Mom wanted to make our oats the best she could. Today, the oats in front of me are well-toasted and seasoned with fresh peaches, bee pollen, my original sweet blend of spices, and salted butter.

Oats still call to me, and I start my day with them often.

If I cook oats for anyone, they are always toasted. Why? Because they’re better that way. And because extra care in the preparation of a plate is tangible. Food is edible love.

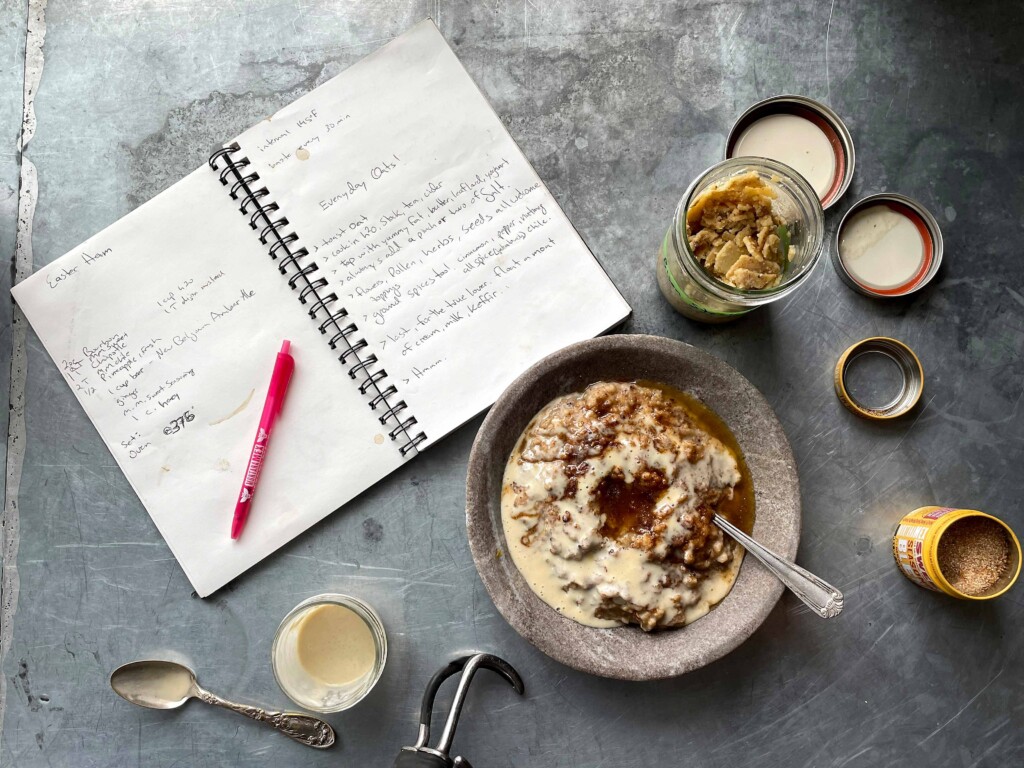

EVERYDAY OATS

Toast oats. Add any liquid and cook, stirring often until tender. Add a pinch or two of salt. I tend to cook my oats in non-dairy liquids such as water, stock, tea, cider. Dried fruit can also be added to this step.

To serve, I top with a dollop of a yummy fat, such as butter, leaf lard, chilled custard or Greek-style yogurt. Dry edible flowers, pollen, herbs and seeds are all welcome toppings. Ground spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice and chipotle chile also add a blast of flavor as an optional finish. Last but not least, for the true oat lover, I float a moat of cream, milk, kefir or custard onto my oats as a rich finish.

Enjoy.

Emigrant, Park County, MT, 1986

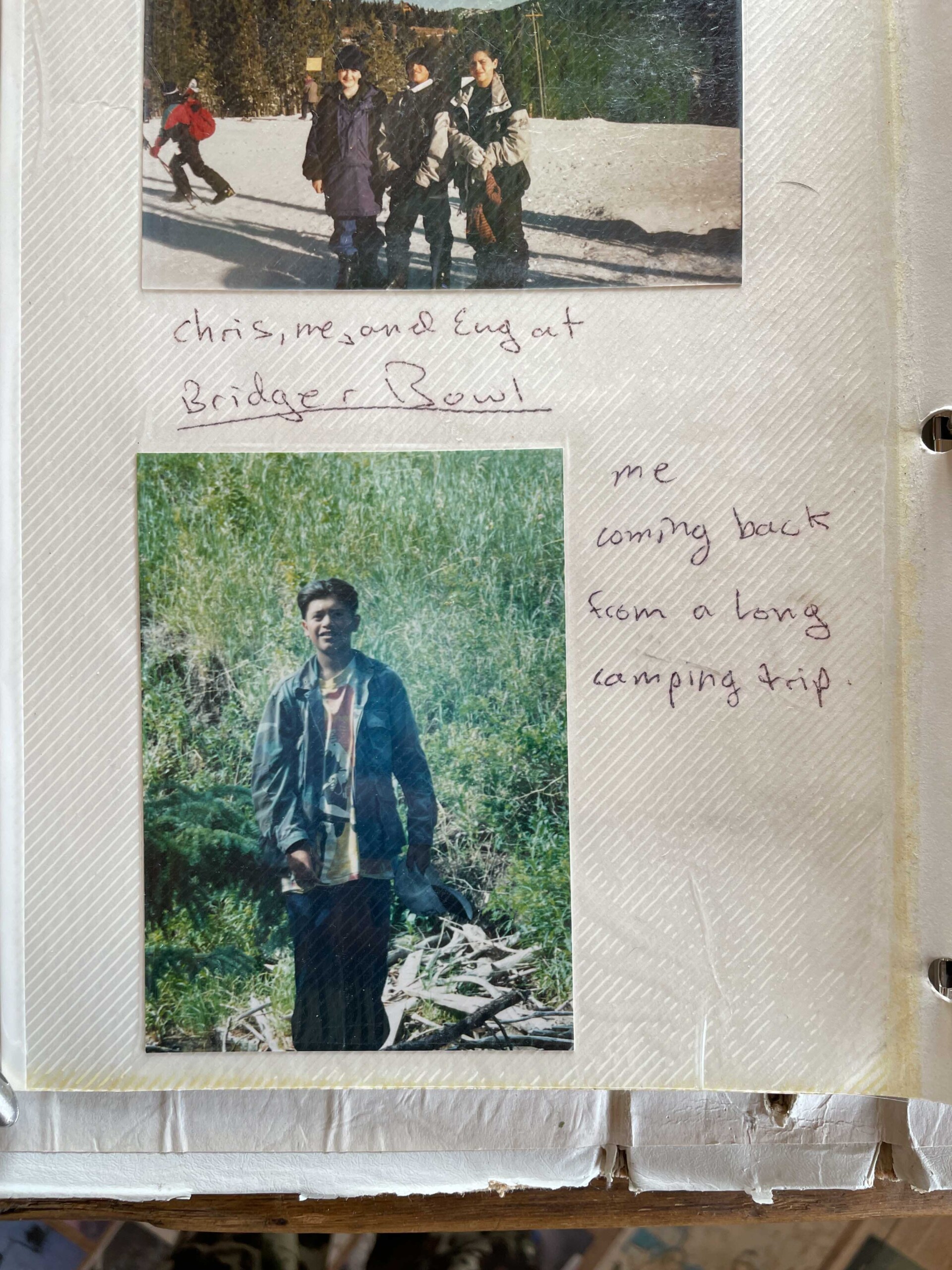

I am six years old. On the morning of our first day in a new home, and for every morning to follow, I stretch and shake off sleep with Emigrant Peak perfectly framed in my bedroom window. A beacon, calling.

My backyard is suddenly the Rocky Mountains. This will be the first time I see myself as part of a place, and it is mine to discover. Safe in the periphery of a small, tight-knit community, we roam. Our range runs down the hill, past the general store to the banks of the Yellowstone River, across the bridge and back up the other side into the mountains. We go as far as our bikes and our snacks can carry us.

We are hungry. For exploration, for freedom, for the wilds — and for food, because the rations we pack are never enough. Expeditions become fueled by forage. We learn the berries and mushrooms and roots to eat, and those to avoid. Someone makes a slingshot. Someone produces a fishing pole. Forays to the river begin to include a stop at the general store for bait and tackle. Rabbits and fish are added to the bounty that our little hands gather from the land.

I come to know the world through the intricacies of the nourishment it provides. Body and soul. I start to connect with the landscape around me.

Emigrant, Park County, MT, 1991

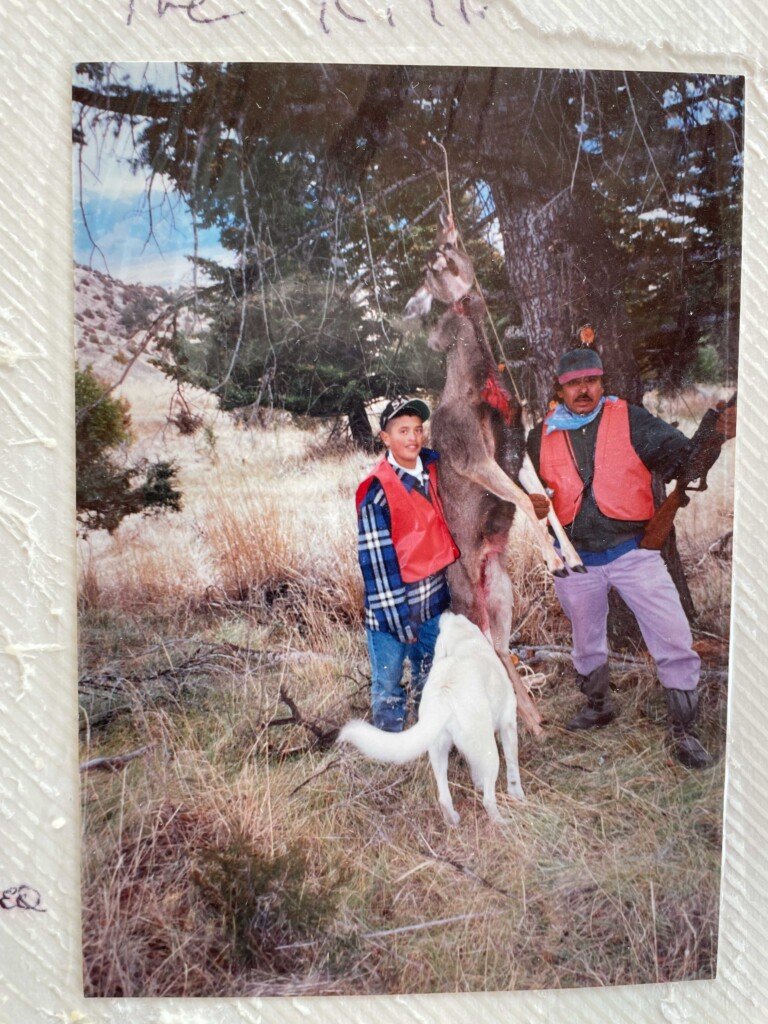

I am 11 years old, and I have visions of fire and feast in my brain.

Armed with a .22 rifle and fueled by scenes from the Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone movies, we set out for the hunt.

The first shot is to the leg. The second shot is a miss. The deer, shocked and injured,

bolts, staggers and stumbles over a cliff. We find the animal in the shelter of a juniper bush, still breathing, the broken leg hanging awkwardly beneath the weight of his body. We did this. We did this! We are out of ammo, and we know we need to end the suffering. I have a knife, so I go for the throat. I’ve dispatched fish like this, and logically this is the same, yet very different.

I remember the gravity of what ensues post-death. We kill the deer … and then what? We have no knowledge of the transition from animal to food. It is easy to see the end result — as a steak. But we have no compass, so we just cut. We plunge knives straight into the hind quarters, because that’s the thickest part of the animal and must be where the steaks are. Hunks of meat are carved straight from the muscle, with sinew and hide still attached. We build a fire, eat our fill, take what we can carry and leave the rest for the scavengers. We tell ourselves that our canine friends, the coyotes, need to eat, too — our moral compasses catching up with the reality of our actions.

That was the first time I truly saw and felt death and life as one. To say it had an impact on me would be a gross understatement. I think about it now and I know we weren’t wrong, we just hadn’t been taught. We had no one to teach us.

What I know now is it’s impossible to watch the passage of life to death and not feel that tremendous transfer of energy. I have learned to not waste it. I have learned to be conscious and intentional. I have learned to hold total ownership for all the life taken to sustain my own.

HEART TARTARE RECIPE

Ingredients:

8 oz heart trimmed (see method below)

1⁄4 cup red onion

1⁄8 cup pickle, chopped

1 teaspoon mayonnaise

1 tablespoon dijon or grain mustard

1 lemon

1⁄4 cup parmesan

1 teaspoon Montana Mex Jalapeno seasoning

Optional:

1 cup watercress

2 tablespoons chopped chives

Method:

Trim fat, silver skin and arteries out of heart. Cut the heart into small strips and then finely dice into small cubes/pieces. Transfer finely diced heart into a mixing bowl. Dice onion and pickle in a fine chop similar in size to the minced meat and add to the heart in the mixing bowl. Add mayonnaise, mustard, lemon zest and Montana Mex Jalapeño seasoning into the bowl.

Stir all ingredients until evenly blended. Check and adjust seasoning to taste. Finish with fresh watercress or chopped chives and grated parmesan.

Enjoy on a cracker, a chip or toasted bread, or wrapped in a lettuce leaf.

Emigrant, Park County, MT, 1995

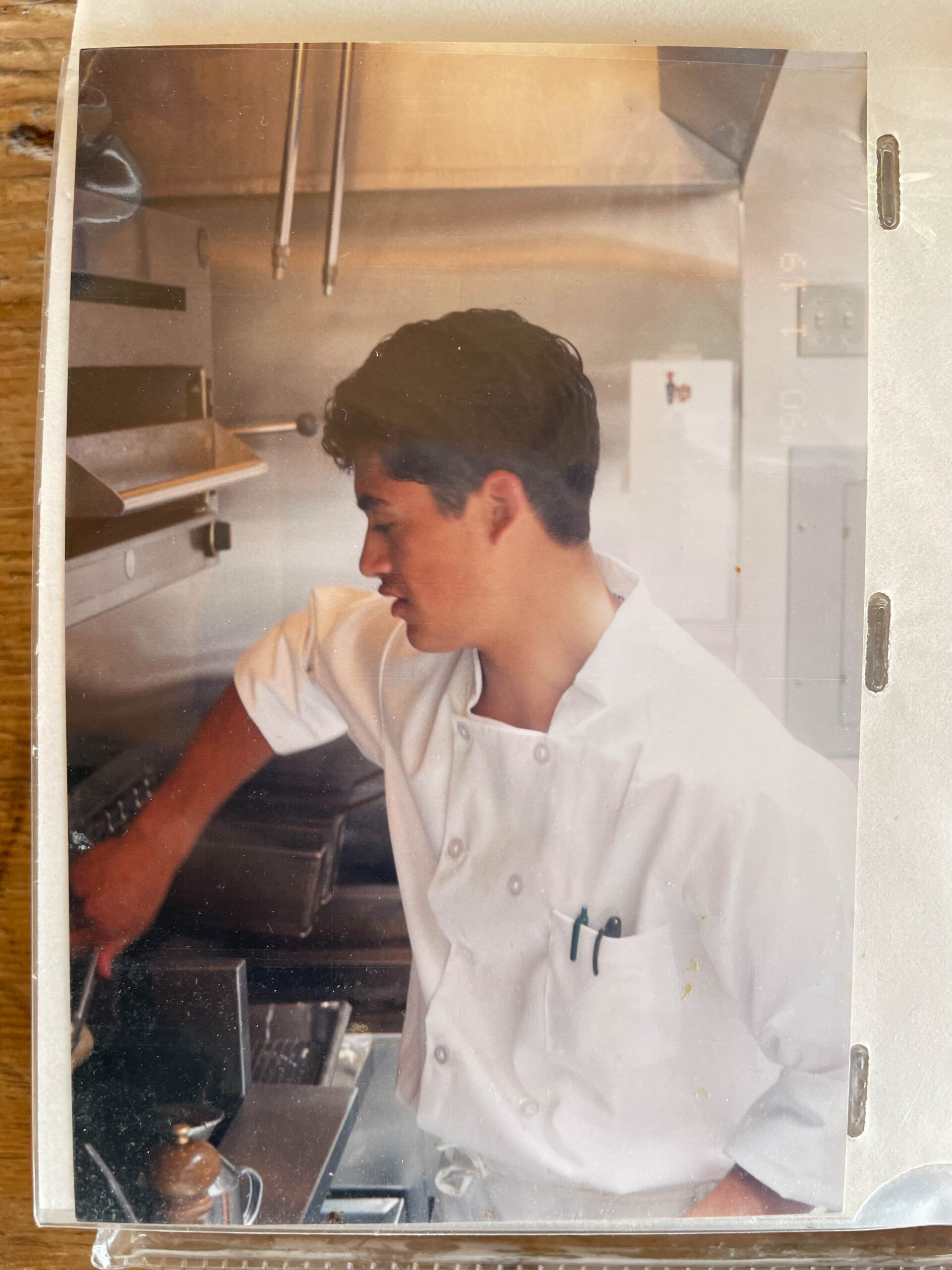

I begin making food for others at age 15. Jonesing for cash to burn, I strike out in search of a first job. In a small town, my options are limited, so I ride my BMX bike with white rubber grips on the handlebars — the words “YO, YO, YO” written all over them — three miles downhill and three miles uphill to Chico Hot Springs Resort. Like so many times before, I open the door to the Poolside Grille and walk up to the cash register. Only this time, instead of a pool pass, I am handed an application. A single 8 x 11 sheet of paper with an official header. Among the many sections of small writing in black ink, one gives me pause. It reads: “cook, prep cook, dishwasher.” Naturally I avoid the third option. I also recognize that I most definitely am not a cook. I recall thinking, What then might be a prep cook? I check the box.

As a prep cook, my first task is to tackle a massive, 30-pound chunk of orangish-yellow, Wisconsin-born, Sysco-brand cheddar cheese. As I crank the grating wheel and tear real estate off the block, I watch delicate strands of cheese descend into the waiting bowl below.

I recall a certain side of my brain feeling satiated in a way it never has been before. I recall making the connection between this huge block of cheese and a favorite dish: nachos. The gooey, crispy, yummy platter of nachos I’ve ordered many times before and consumed with gusto only a room’s length away, suddenly come to life.

Fifteen minutes into that first task, chef Justin Smith pops into the prep kitchen to review my work. He nods in satisfaction and says, “When you get that job done, clean it up and come on up to the front. I’ll teach you how to make a pizza.” And there it is — on my very first day as a prep cook, I graduate to cook. I build nachos from the ground up. I learn what dough is and how it becomes pizza. I throw food in the air and witness methodology that feels more like play.

Oh, I think to myself, this is going to be a good ride.

FORAGER PIZZA

Prep Time: 15 Min.

Cook Time: 12 Min.

Serves: 2-4

Ingredients:

1 tablespoon olive oil, divided

1⁄4 pound mixed wild mushrooms, thinly sliced

1⁄4 teaspoon kosher salt

1⁄4 red onion, thinly sliced

2 cloves garlic, chopped

Semolina flour, as needed

1/2 pound pizza dough (recipe follows)

1⁄4 cup raw red sauce (recipe follows)

2 tablespoons nettle pesto or other pesto

3/4 cup shredded low-moisture mozzarella cheese

1/2 link cooked Mexican chorizo sausage, thinly sliced 1⁄4 teaspoon dried Mexican oregano

1/2 cup grated cotija cheese, divided

Method:

Preheat the oven to 500 degrees. Position one rack on the very bottom of the oven and one on the top third.

Heat a small skillet over medium high heat. Add the oil and heat for another 30 seconds. Add the mushrooms to the hot pan and season with the salt. Stir to combine. Cook the mushrooms undisturbed for about 3 minutes. Stir so the browned mushrooms at the bottom are now on top. Continue cooking, stirring occasionally, until evenly browned, another 4 minutes. Sprinkle in the onion and garlic, and stir to combine. Remove from the heat and set aside.

Using fine semolina flour, lightly dust a pizza peel or use the bottom of a cookie sheet pan. Stretch the dough into a 10-inch round, letting it fall and drape over your knuckles to stretch itself naturally. Place the formed dough on the floured tray. Dot the dough evenly with the sauce. Sprinkle with the mozzarella and dot with the pesto. Scatter the chorizo on top. Spoon the mushroom mixture evenly over the chorizo and sprinkle with the oregano. Finish with 1/4 cup cotija cheese. Place the tray on the bottom rack and bake for 5 minutes. Move the tray to the top rack and continue to bake until deep golden brown and crispy around the edges.

Remove the pizza to a board and top with the remaining cotija. Cut into wedges or squares and serve.

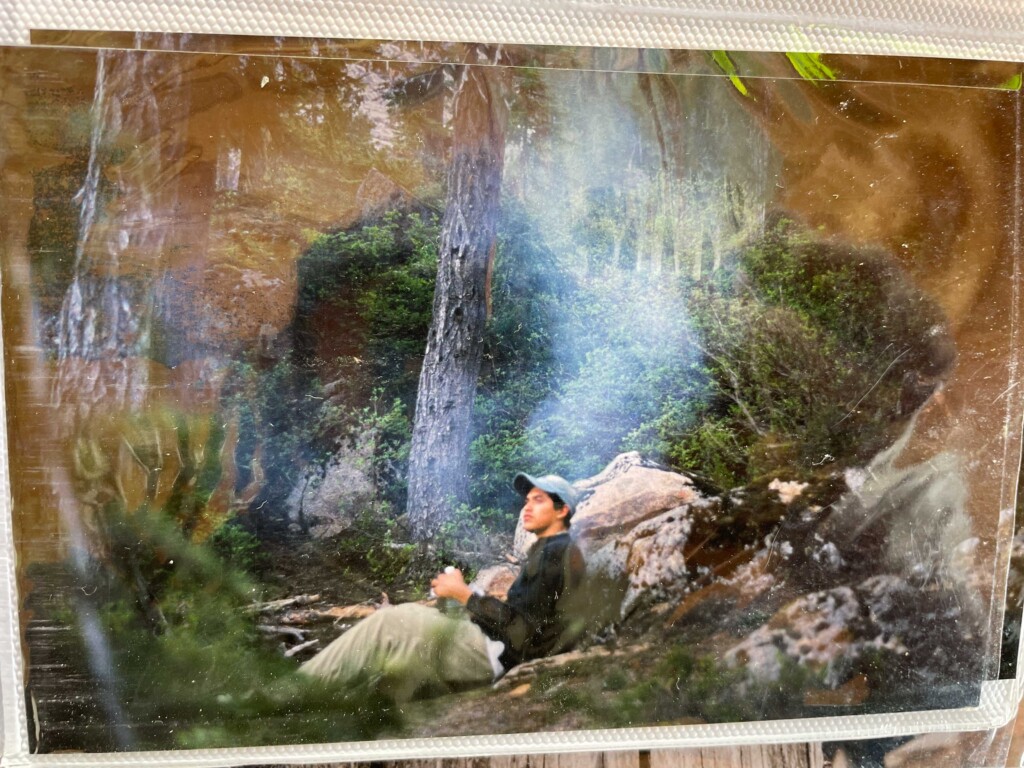

Seattle, King County, WA, 1999

The mountain stream cascades into the river that flows faithfully lower and out of the mountains to the salty embrace of the sea. I have similarly made moves down the mountain. I am a small fish in a big pond. A country mouse in the big city. My formal education into professional cooking begins in the fall of 1999 at the Art Institute of Seattle’s Culinary Arts program.

I am 18. My range now runs from the Magnolia neighborhood, 15 miles down the hill, through the streets of downtown, all the way to the piers lining Puget Sound. Again, that familiar hunger. Every morning, on fresh legs, I race the city metro on my mountain bike. With enough red lights, I can squeak ahead and claim a small, silent victory in a race where me, myself and I are the contest — the opponent and the only spectator.

I take on cooking school like a new relationship. It is oxygenating to be surrounded by such a variety of life while also deeply stimulated in a specific focus. I struggle to complete the curriculum-based work that requires sitting and writing — not a new phenomenon for me. I am, and always have been, ignited by work that involves active learning and physical movement.

In the late afternoons, school gives way to work, but even there, it feels like class is always in session. The restaurant kitchen moves at a very different pace while still being a powerful teacher. School digs deeply and deliberately into the fundamentals of cooking methodology, history, action, reaction and innumerable other details that seem to stretch and flourish and become accessible to the mind of the student. My work at the restaurant demands a timely outcome. The same chicken stock I spend days perfecting and slowly working on with my fellow students at school comes to life in the bustle and buzz of the restaurant at an incredible rate.

There is a harmonious juxtaposition between the different styles of teaching at culinary school and work, but when it comes to either kitchen, there is a fire inside of me that has been lit and cannot be snuffed out. It burns brightly enough to keep me awake during this exhausting and rewarding time of my life.

During my two-year journey at school, I work every day of the week. I at-

tend classes. I work at restaurants, sometimes two or three at a time. I take gigs modeling for bronze sculptures — anything to pay the mountain of bills I’m accumulating. With an intense schedule, Sunday mornings before a 2 p.m. shift at the Flying Fish are often the only free time I have in any given week — I cherish it.

Every two weeks, after I pay my bills, I find an extra $60 in my pocket. Naturally, I do the only responsible thing: I head to Saito’s Japanese Cafe and wait outside for the door to open exactly at noon.

I am usually the first customer, and I sit squarely in front of Chef Yutaka Saito at the sushi bar. He greets me and asks what I would like to order. I put my $60 on the counter and say, “Whatever this will buy.” I blow it all on myself, and it’s worth it. As my order is made, I get low to my seat, drop my chin onto folded hands and watch Saito move. He does so much more than just roll sushi. His actions are fluid. He moves with the aplomb of a polished boxer, bobbing and moving his body as he cuts and rolls. His culinary ballet is filled with character and a sincere devotion to method and detail. His carbon steel blade never misses a beat.

So much is new, and yet in the bites of carefully crafted and thoughtfully seasoned morsels of Japanese cuisine, I fall in love with the old. As I finish each Sunday supper with a hot bowl of miso soup, I feel happy and at home. I walk my bike to work, digesting the experience. The comfort I’m feeling within was planted many years before by a mom hustling to get food on the table. (The number one breakfast my mom would make was oatmeal; the number two was miso soup.)

Because I am a regular, Saito knows me. And it is on one of these Sunday lunches that Saito asks me how school is going. Graduation is only months away, and he’s noticed my intense interest in what he does behind the counter — heady moments often only interrupted by pauses to actually eat the food I’ve ordered. On this day, he sees my questioning eyes and he asks, “You like sushi?”

“Yes,” I reply. “I love it.”

Saito responds, “I’ll show you if you want to try.” And so, before I graduate culinary school, I start working at Saito’s Japanese Cafe.

In the year I work there, it is Saito who says to me, “You’re getting better Edo-San, but you can always be faster. Approach your work every day like a fighter. Never get lazy, and try to be better. Every time.”

I will lean on these words and my teaching from Saito my entire career.

MISO SHIRU

Miso shiru or Miso broth is an integral component to a traditional Japanese breakfast and makes a common appearance at lunch and dinner.

At its core, miso is a nutrient-rich brothy soup made on the backbone of fermented soybeans and, sometimes, other grains and beans. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of variations of miso in Japan and, of course, wherever else in the world miso is made – all different in color, taste and composition. The creation of a miso and then the selection of a miso for a dish like a soup, sauce or dressing is largely guided by region and personal preference.

In my home, we swing through all types of Miso soups. Clear broths studded with seaweed and mushrooms to large pots loaded with bison tendon, radish, ginger and other aromatics. I also tend to combine varieties of miso. Called Awasé, this practice of building a miso allows the cook to customize the color, texture and flavor of the finished dish.

I start here:

2 1/2 cups stock, water at a low simmer 4 tbsp miso, whisked into the liquid

I then add:

Vegetables, cooked meats, egg, fish, seaweed, tofu.

Take care to not boil the miso as the higher temperature will kill some of the core nutrients. I let this cook together at a low simmer until the added ingredients are cooked to my liking. I then check its flavor. I like spicy soup and tend to float a sprinkle of Montana Mex Jalapeno seasoning on top with a drizzle of toasted sesame oil to finish.

To serve:

Often, I will add warm cooked rice to my bowl before ladling soup over it. I find adding thinly sliced green onions adds a bright herbal note with a pleasant bite of onion to my favorite soup of all time. Nutrient-rich and ever-diverse and variable, Miso shiru.

Seattle, King County, WA, 2001

I am in a kitchen classroom with sweeping windows that take in Mount Rainier to the east and the moving waters of Puget Sound flowing west toward the Olympic mountain range. I am tweaking the dessert component of my final menu. This is the penultimate project I will work on before graduating with a degree in the Culinary Arts. My student loans require full repayment in six months. Although I am working on a chocolate ganache and paying close attention to temperatures and times, my mind is heavy with the financial burdens that accompany my degree. I am already working two jobs and looking at the reality of needing to pick up a third and potentially fourth to cover my bills. I am worried.

“There’s a job I think you should interview for and take.” A voice breaks the still silence of the kitchen.

Chef Instructor Robert Wood walks into the kitchen and approaches me with an offer. “There is a yacht docked at the harbor, and they’re hiring a chef,” he tells me. “This is a job one should not refuse.”

Intrigued, I ride my bike down to the harbor where the yacht, Dorothea, is moored.

My interview goes well, and I bike home. Days later, Captain Mark Drewelow calls to offer me the job.

I think of my looming debt. I think of exciting adventures at sea, unmoored. I think of Chef Yutaka Saito, the Tokyo-trained sushi chef teaching me an incredible amount.

I turn down the job.

Seattle, King County, WA, 2001

It’s 10 a.m. The phone rings.

“Hi, it’s Captain Mark Drewelow from the yacht Dorothea. Remember us?” he asks. Yes, I do. “We are looking for a chef again, and you’re at the top of the list. This will be your second and last shot. So if you want the job, let me know. You got a week.” The call ends.

I imagine the easy-going, adventure-rich lifestyle of boat life at sea. I imagine the fun scenes from the movie White Squall. I can’t help but become seduced by the idea of what it would be like to cook around the world.

This time, I take the job.

These excerpts are just the first steps in an ongoing collaboration with Chef Eduardo Garcia (@chefeduaradogarcia). We will continue this journey both online and in our next issue as Eduardo dives deeper into his relationship with food and how it brings meaning and magic to his life.

Related Stories

Latest Stories