Your cart is empty

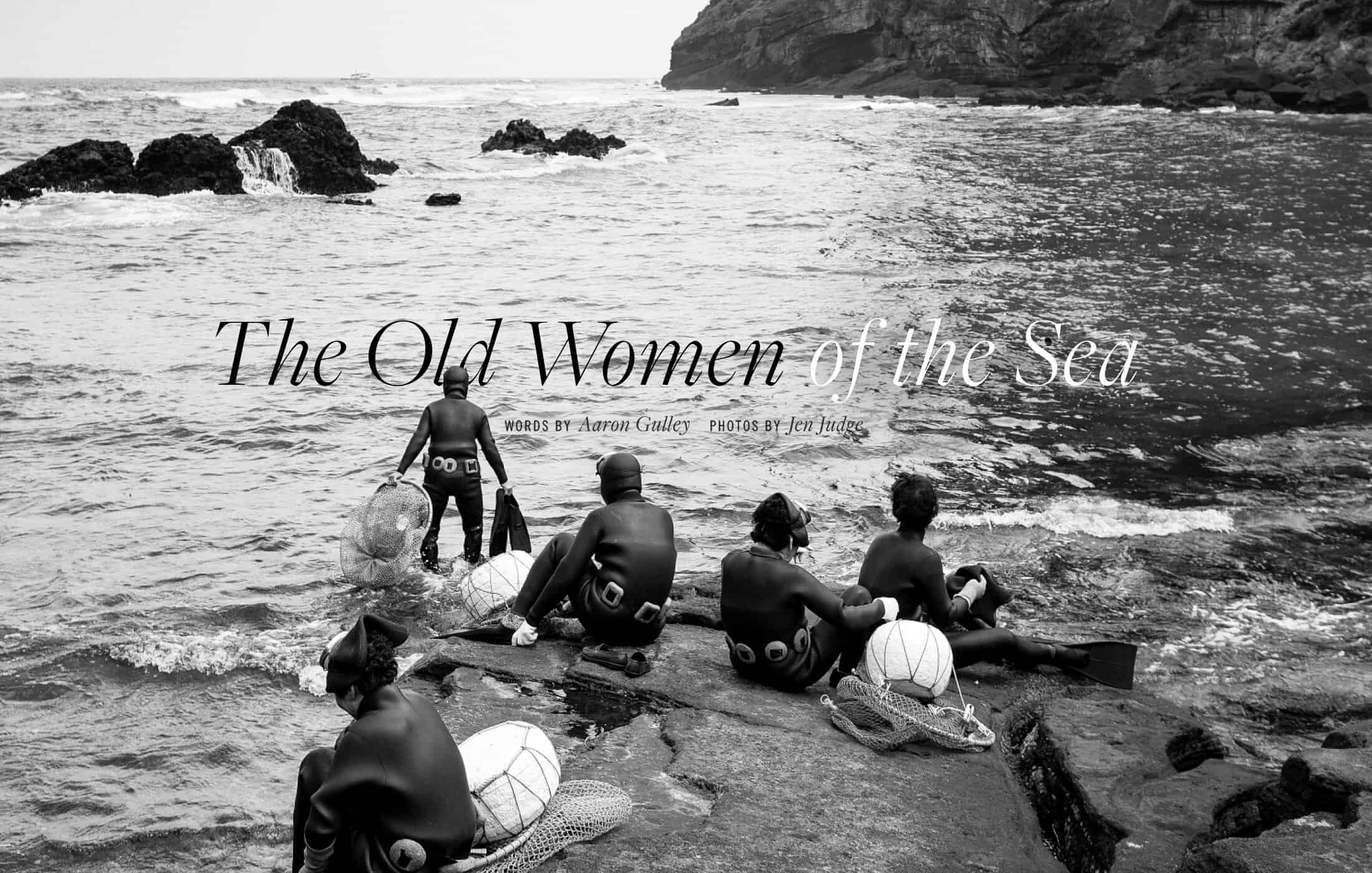

Five Korean grannies with painted-on eyebrows and perm-fluffed hair are preparing to walk into the frigid East China Sea. It’s a raw morning in the wind-lashed village of Hado, on the eastern coast of South Korea’s Jeju Island. I’ve come to visit these haenyeo (literally “women of the sea”) for a lesson in the art of freediving.

A cold drizzle has me on edge, but the ladies seem not to notice. “Don’t you want to dive with us?” one sweet 72-year-old asks. The truth is, with rain ratcheting up and water temperatures hovering around 57 degrees, I can’t think of anything I’d rather do less.

For the women of Jeju, diving is life. They dive to harvest abalone, conch, octopus, urchin and seaweed. It’s work that’s reserved for women, which I’d read stemmed from a historical legal loophole that exempted husbands from paying taxes on their wives’ earnings. The truth, I’d find out, is bleaker. The women of Jeju took up diving as early as the 17th century to support their families because their sailor husbands were frequently lost in the treacherous seas. It’s possible that the work also fell to the women, much the way it did among the ama pearl divers of Japan, because, with slightly higher levels of body fat, they could better endure the cold waters.

Jeju still has about 5,000 working haenyeo, though the trade is dwindling as young girls gain access to education and easier livelihoods. The women still diving, most of whom are over 50 years old, are emblematic of Jeju’s past, where life was a struggle against the harsh marine environment and people did what they had to do to eke out an existence.

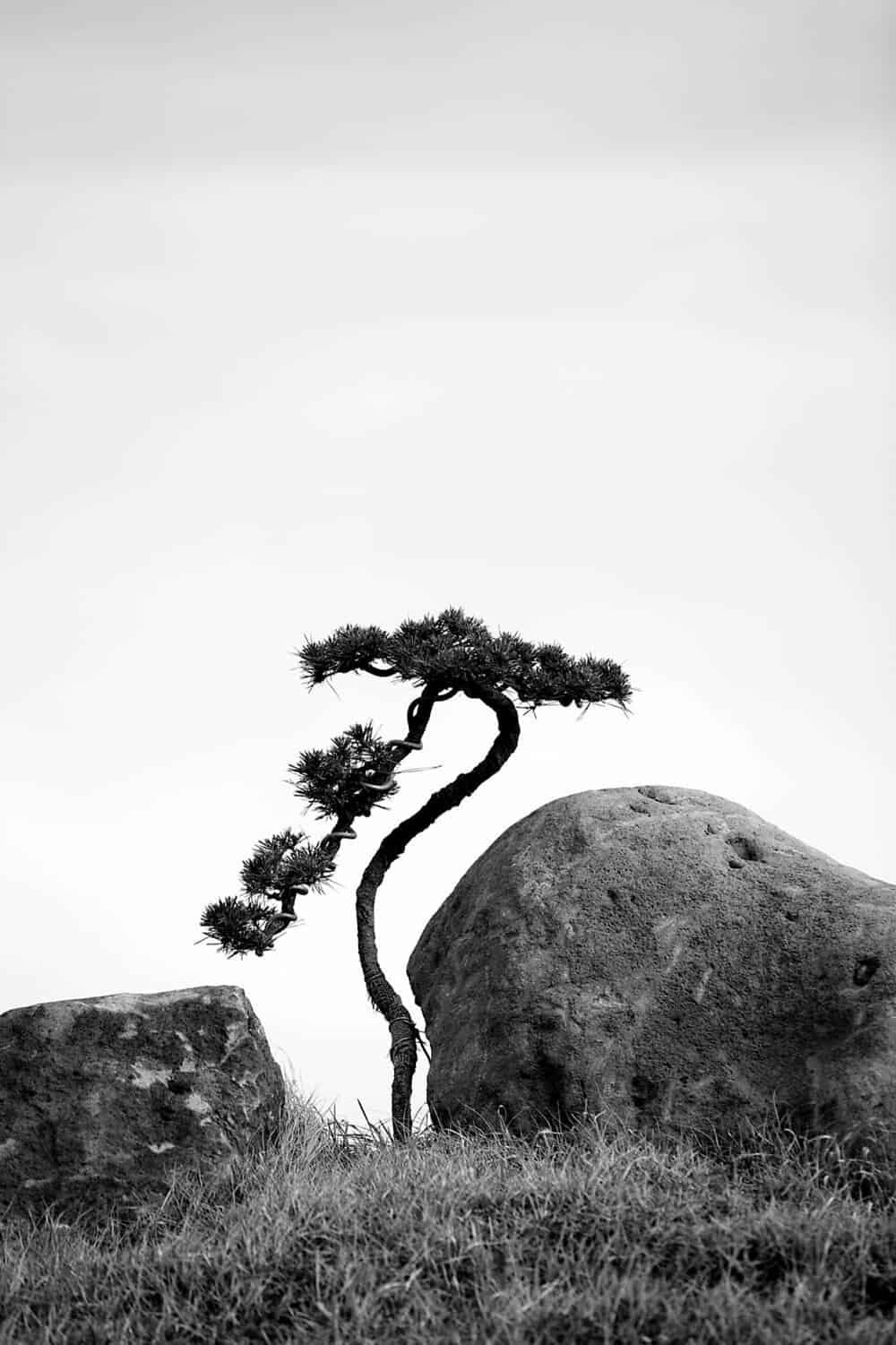

“Jeju is known for three things,” my guide and translator, Sunny Hong, told me on arrival, quoting a local maxim. “Strong winds, strong rock, and strong women.”

“Jeju is known for three things,” my guide and translator, Sunny Hong, told me on arrival, quoting a local maxim. “Strong winds, strong rock, and strong women.”

I’m up against them all in Hado, where I realize that I’m going to have to get wet despite my misgivings about the conditions. As the five haenyeo trudge into the inky water, I wrestle with my wetsuit, which feels as difficult to don as an octopus costume. By the time I’m suited up, the old gals are emerging from the sea. The swells are rising, one tells me, and it’s no good for harvesting shellfish today, though I notice that each woman carries a small net of crustaceans they’ve gathered. The women motion for me to follow them into their stone warming hut. Once they’ve built a fire, they press whole fresh abalone into my mouth and feed me spoonfuls of urchin roe. The haenyeo may be tougher than walrus hide, but they’re still grandmothers at heart.

I ask the women about their work. Yoon Bok-hee, a pudgy 70-year-old who identifies herself as the head of this unit, tells me that they sell the seafood they harvest to a cooperative, which in turn sells to restaurateurs and fish markets both domestically and abroad. There are small units of 15 to 20 women like this one all over the island; Hado has seven such groups. The women work at depths between 15 and 70 feet without any breathing apparatus, partly because they began diving before such innovations and partly as a limit on how much each can take. They dive approximately 150 days each year, according to the tides, and spend between four and six hours in the water each shift. Most suffer from headaches and ear problems, and all of them say they know at least one woman who died while diving. The work is so grueling and treacherous that, according to one timeworn expression, “It’s better to be born as a cow than to be born as a girl on Jeju.”

I ask if they make a decent living. “We don’t need to dive anymore. We have plenty of money,” Yoon Bok-hee tells me as she cleans her mask. “But we like to come here and be together. It’s our community. Our children tell us not to dive anymore. They want us to come take care of the grandchildren. But that would be like a jail sentence. Our life is here, on the ocean.”

This is the paradox of today’s hunters and gatherers. Faced with the conveniences and structures of modern life, once-fundamental pursuits are becoming superfluous, skills and knowledge lost. But even as society shrugs them off and admonishes their pursuits as arcane and frivolous, these haenyeo seem to remember that diving is more than just the basic pursuit of food. The visceral act of striving to exist in the elements binds us to the natural world, and doing it collectively underscores and defines our humanity.

The women, who are unrecognizable from their seagoing selves after they emerge from the showers with rouged cheeks, primped hair, and Louis Vuitton bags, tell me to return to dive with them in a few days when the forecast is better. On the appointed date, the weather is even more ominous, a cloak of cold mist hanging eerily over the island. But at the stone warming hut, 15 stout old women are prepping their gear, oblivious to the freezing drizzle. “You can’t choose the weather,” says one of the divers, 64-year-old Kim Doo-soon, explaining that the haenyeo were often forced to work in spite of the conditions, since their livelihood depended on it. “Before, we had to dive if we wanted to eat.”

I follow the grannies — several of them in their 70s — down an algae-slick concrete path to a rocky point where we put on our fins and clamber in. My hands go instantly numb and the cold stings my face despite my mask and hood. The women kick out into the black maw of surf, and I fall behind trying to adjust my gear. By the time I catch up with a small cluster of divers, we’re over half a mile offshore and I’m winded from exertion. The haenyeo bob in the waves, laughing and chatting as they hang on to the personal floats attached to beanbag-sized nets they’ve each dragged with them.

Kelp shrouds the sea floor in a thick carpet of crimson and thrusts up toward the daylight in ropey vines that sway and surge with the waves. The haenyeo kick down 50 feet to the seabed and plunge into the thick foliage to root around for their quarry. Each carries a J-shaped metal hook in one hand, which they use to prize abalone from the rocks with a sharp twist. One minute passes, sometimes two, before they finally stream back to the surface. As they crest the rollers, they let out a massive exhalation of carbon dioxide in a stiff, shrill squeal. All young haenyeo girls are taught this breathing technique, called sumbi. I rarely see a woman ascend without at least one or two abalone, and their nets begin to sag. They only stay above water for a minute or two before flipping over and repeating the process. It looks as easy as plucking tomatoes.

I try finning down with them a few times, but by the time I reach the bottom, my lungs are burning and I have to kick back to the surface. I give up and observe, and after an hour of inactivity I’m trembling from the cold. I wave goodbye to the women and fight the waves back to land, where I steal a hot shower in their women’s-only bathhouse.

Warm again, I sit down with my umbrella to wait. I snack on rice and seafood rolls called kimbap and huddle against the wind. The day stretches on, past the sun’s zenith and into the afternoon, and I’m flabbergasted the women are still out in the icy water. Unlike many delicate grandmothers back in the US, these old women are as robust as many Olympic swimmers. One irony of our existence today is that as technology makes life easier, it also makes us softer and less self-sufficient. When the day comes that there are no more haenyeo, not only will we have lost this wild and stalwart culture but, as a species, we will be one step farther from being able to exist in our natural world.

Finally, around 3 p.m., some six hours after they went out, the haenyeo begin floating in one at a time, their nets bulging behind them. Some of the hauls are so substantial that it takes two or three women working together to drag them from the water. With their harvest safe, the haenyeo scrabble from the icy froth and totter over rocks that glisten like polished onyx, tiny black sea creatures from a bygone age coming ashore.

Related Stories

Latest Stories