I was out of my comfort zone. There’s no doubting that.

The muggy hustle of London footfalls flowed around me in an effortless weave of practiced daily routine. Even working in Edinburgh had been an adjustment for me, but London was more than a short drive to the hills I called home. The Thames River offered a slice of normality — a calming, steady flow and rhythmic burble of running water gifting a portal of escape. I was a caged lion here, a hunter longing to see the dancing roll of grasses on the savannah. Walk free and feel the granules of sand sink beneath my feet; inhale the earthy, humid musk of fresh rains on baked soil. Yet for all its seemingly distant association with the tangible life I sought, it was home to one of the great English gunmakers, renowned the world over. Cemented into history alongside the most respected hunters and explorers to walk the earth, I had known the company name long before I even owned my first rifle.

That was in my early twenties, and I made more than one visit to the Bruton Street showroom of Holland & Holland during the time I return, but this time on a generous invite to not only look around the gunroom, but also meet with the Managing Director, Daryl Greatrex, and visit their factory premises and shooting ground. Not to be passed up lightly, I didn’t need much convincing to fit it into my schedule.

Exuding class and sophistication from the moment the front door opens, the gun room sits toward the back of the shop; a beacon of irresistible temptation for any scholar of fine guns and history. Slowly passing along the racks of shotguns and rifles, I was fully aware of my inability to truly take in what I was seeing. Expertly selected fine walnut, oiled in deep lustre, matched in harmony with cold metal workings, blued as deep as the ocean. Even to the untrained eye, the attention to detail was incredible. These were not guns, they were functional works of art.

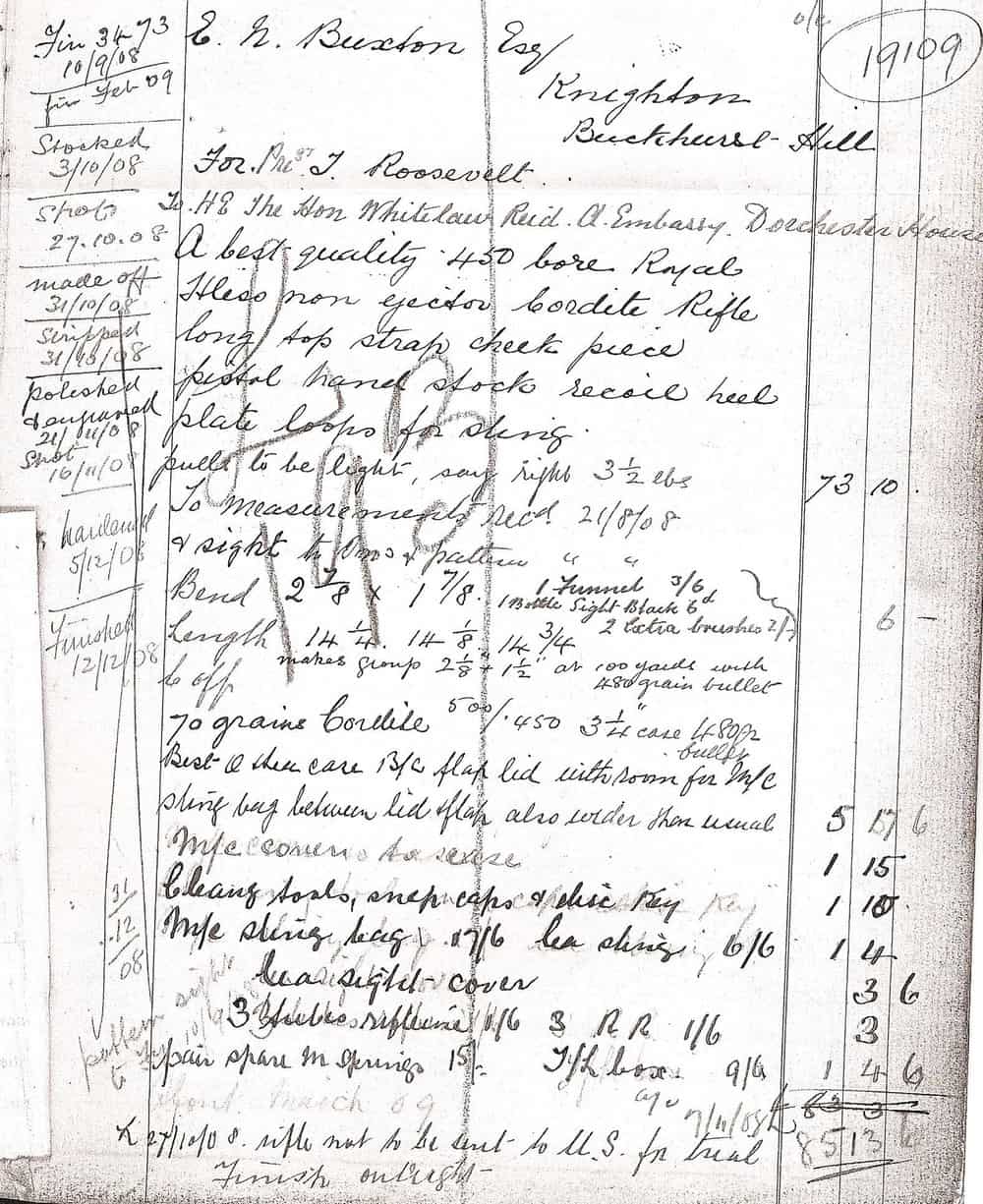

Day book entries for no. 19109, the royal hammerless rifle made for Theodore Roosevelt. The rifle, plus accoutrements, cost around £85 in 1909.

In recounting this trip to a friend just a few days ago, I was asked if I thought these fine, handmade guns were really worth it. “Are they that much better?” was the throwaway question thrust in my direction. Define “better” for me.

In the past, it could be argued that the craftsmanship fostered at Holland & Holland allowed them to produce some of the most accurate rifles of their time. This was displayed in dominant fashion during the 1883 Public Trail of Sporting Rifles, put on by The Field Newspaper. Holland & Holland was the only company to enter rifles in all ten categories, taking home the winning place for every single one. The results were nothing short of spectacular, especially when digging into the details of average group sizes compared to their competitors. Today however, it would be a stretch to expect this to be replicated. Modern advancements in machining and tolerances mean that extremely accurate rifles can be made for a fraction of the cost of even a second-hand Holland & Holland. Yet, as I contemplated my reply, pausing for a moment to reflect on my day learning the inner workings of the company, the answer was clear.

“When you pick up one of your rifles out of the cupboard, what do you feel?” I motioned with my hands as if to grip an invisible stock, looking over to Edan for his comeback.

Before he really had a chance to think about it, I interjected, “There is no other way of putting it, but when you hold a Holland & Holland in your hands, you know that gun has soul. Beyond man hours involved, there is something almost inexplicably magical about it. That’s the best I can do; they aren’t really comparable with anything else.” More than that of course, they function with flawless reliability on the back of hundreds of thousands of hours of experience over 184 years. Fitted to the finest detail of every customer’s stature, an accurate rifle is a default when buying a Holland & Holland. It’s an object of great beauty and sophistication, morphing form, function and aesthetics in a way only really possible with the finest English guns.

“These were old-world, skilled craftsmen living in a modern era.”

After handling several shotguns and rifles in the showroom, profusely apologizing for leaving my paw prints all over them, I was taken to the underground labyrinth of rooms for a meeting with Daryl Greatrex. It was an opportunity to satisfy my intrigue with their heritage and hear firsthand about his vision for the future of Holland & Holland in an ever-changing world.

To recount their history with any kind of completeness would require an entire volume of Modern Huntsman dedicated to the cause. Indeed, Donald Dallas completed the latest revised edition of Holland & Holland, The Royal Gunmaker, The Complete History back in 2014 (I owe much of the historical references to that excellent publication). The 440 exquisitely researched and referenced pages are a testament to the heritage, innovation and longevity of this British gunmaking icon. However, I will provide a brief, severely abridged version of their origin.

It will come as a surprise to many that H&H did not begin their journey as a gunmaker. The founder was Harris John Holland, born into a family business of skilled craftsman making barrel-organs. By the 1830s, a young 20-year-old Harris switched vocations entirely, opening up his own retail tobacco shop at 5 Kings Street, Holborn. In the early 19th century, the tobacco trade was booming and provided a much more profitable endeavour compared to the difficulties he had faced running a successful music business.

By 1848, Trade Directory records show Holland listed as not only a ‘tobacconist’ but also a ‘gunmaker.’ The official established year for the company is recorded as 1835. The reason for this foray into gunmaking spawned from his own personal interest in pigeon shooting (and later, competitive rifle shooting).

By 1844 Harris had welcomed the birth of his nephew Henry William Holland, whom he would take under his wing as guardian upon the death of his younger brother, John Holland, in 1857. At the time, young Henry was just 12 years old. By 1876, after serving his apprenticeship, Henry would become a partner in the firm. From this point on, the company would be known as Holland & Holland.

There is no question that the success of today’s company was built on the foundation of these two men, with the younger Henry taking the reigns upon the death of his uncle in 1896. Henry proved to have not only enviable business acumen, but also a thirst for invention. He would expand the business to become arguably the largest gunmaker in London, setting up the first modern gun factory designed specifically to this end. The building, 20 minutes from today’s showroom, stands as it did more than 100 years ago, as I bore witness to during my tour. Even now, Henry looks over the day-to-day workings from his place of rest in the cemetery opposite the factory.

As I stood on the fourth floor, peering through the blinds, surrounded by rows of benches laden with tools and gun parts, the visceral scents of oils and steel swirling around my nostrils, ears filled with the indiscernible bustle of metal-working, I couldn’t help but wonder what Henry Holland would make of this today. Could he possibly have fathomed that the old-world skills he helped develop and pass on would remain for the most part unchanged for nearly a hundred years after he began?

Before his death in 1930, Henry had succeeded in reaching the furthest depths of the British Empire with his guns and rifles. He would be remembered as one of the most prolific gun and cartridge inventors of all time, registering no less than 47 patents to his name. The company would also go on to secure a number of Royal Warrants over the years, presented in recognition of those who have supplied goods or services to a royal household. Their first came from the King of Italy in 1883, and the most recent was given by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales in 1995.

From the outside, the factory at Kensel Green looks like many industrial buildings of the era. Red brick walls tower four stories high, with evenly positioned, body-length windows along each floor, maximizing natural light in the workshops. I paused for a moment outside, tricking my brain into removing the cars, the drone of machinery, the planes overhead; little seemed to have changed from the old black-and-white photos I’d seen.

For the next few hours, we toured the factory, moving from the more modern machining of raw, drop-forged materials at ground level, up through the building, floor by floor, following the journey from jagged lump of steel to the delicate and meticulous process of a final marriage between wood and steel. It was astounding, and quite impossible to fully comprehend unless witnessing in person. The level of care, skill and dedication which goes into every gun bearing the Holland & Holland stamp was unlike anything I had ever seen. These were old-world, skilled craftsmen living in a modern era. Every single component was made in-house; from the rifling of the barrels to the smallest screw and spring, someone in this building was responsible for its creation.

It was all too easy to drift off into a nostalgic stupor when surrounded by such history. So many of the fa med hunting stories I grew up reading had a Holland & Holland at their core, and now here I was, standing in the same workshop these great rifles had passed through.

Few remain as legendary as the .500/.450 double rifle supplied to the grandfather of conservation and modern wildlife management, President Theodore Roosevelt. In preparation for an African safari in 1909, he enlisted now-famed hunters Frederick Courtney Selous and Edward North Bruxton to organize his expedition. This included the commission of a rifle from Holland & Holland, a Royal hammerless, sporting 26” barrels and folding leaf sights at 100-yard increments out to 300 yards. The records for this can still be found in the archived Day Book for no.19109, noting the various stages of manufacture up to completion on December 12, 1908. The rifle was delivered to Roosevelt in early 1909 as a gift, funded by no less than 57 English admirers of the President. One hundred years later, in 2009, a commemorative rifle was built as part of “The African Hunter Series,” known as The President Theodore Roosevelt Rifle.

Upon receiving his rifle, Roosevelt wrote a letter to Bruxton. “…it is a perfect beauty. The workmanship is like that of a watch…I cannot say how delighted I am with it…” This is as good an endorsement as any gunmaker can wish to have.

Holland & Holland exists today because of innovations of the past and a constant drive to think ahead of the curve — not only in terms of technical patented designs from ejectors to trigger units, but also in how their legacy of proprietary cartridges have stood the test of time. Many modern derivations of cartridges take inspiration from wha t Holland & Holland achieved over 100 years ago. Arguably the most famous of these lives on today as one of the most popular big-game cartridges in the world: the 375 H&H, developed in 1912, even then able to push out a muzzle velocity of 2800 fps from a 235-grain projectile. However, it is their drive toward a long-term future that captured my interest most.

A company clearly conscious of not standing still, they have managed the feat of staying relevant, while holding firmly to the labor-intensive, hand-made excellence of their core business, which is so often lost in the modern age.

As an industry, we spend a lot of time reminiscing about the past, talking in fond, hushed tones a bout the great hunters of yesteryear. Many of these now-famous names carried equally esteemed rifles and shotguns adorned with the Holland & Holland hallmark. I often wonder what great achievements and names will be remembered from my generation. Will my children’s children be as eager to learn of the exploits of W.D.M. Bell, Hemingway and Corbett as I was, or will more modern names, yet to rise the ranks, be their heroes? At home in the UK, we face an aging population of people who fish, stalk, shoot and hunt, and I can’t help feel we haven’t put enough into nurturing and creating opportunities for new people. I put this to Daryl Greatrex when we sat down over coffee, asking him about the future of the industry.

A wry smile crept over his face as he prepared to answer. My question couldn’t have been better planted if it was planned, as Holland & Holland find themselves just under a year into their new apprenticeship program, training up young gunmakers from the very beginning of their careers. With great pride and satisfaction, Daryl explained how important they felt it was to invest in the future through training, offering a gateway for young people into gunmaking, and protecting not just their own heritage but the long tradition of world- renowned British gunmaking.

Sam Kilduff, 18, and Iona Macpherson, 20, the first winners of the Holland & Holland Conservation Bursary Scheme. Iona will be carrying out a trial to investigate the effect of tick control for sheep on the welfare of ground nesting birds in the Angus Glens whilst Sam will be traveling to New Zealand for two weeks to learn about the protection of indigenous wildlife through innovative predator control. Both projects will enable the winners to develop their understanding of conservation and contribute to the wider rural community in Britain.

They received 350 applications in response to their apprenticeship program, which would take successful candidates through an initial two-year, pass-or-fail training, before continuing on to three years of honing their skills as journeymen. After this, the apprentices would be an independent part of the team, held to the same high and exacting standards as every other craftsman in the company. With interested candidates from as far away as North America, they would eventually whittle it down to just six, a process which H&H intends to repeat every two years.

Toward the end of our tour around the factory, I had a chance to meet the apprentices in their purpose-made workshop. Under the watchful eye of Paul Yelverton, Holland & Holland’s longest-serving gunmaker, each one of them was studiously focused on their task of hand making their personal tools for the years ahead. Not only was it invigorating to see such enthusiastic youngsters, but also to see that they were not at all in keeping with the male-dominated profession of gunmaking — half of the apprentices were women.

I spent some time finding out a bout everyone’s background, and why they chose to pursue this rather unusual career. The common theme that ran through all of them was a thirst to learn a real craft, building unique skills of the trade that are so far removed from most people’s normality. They all seemed as invested in the future as Holland & Holland was in theirs.

A company clearly conscious of not standing still, they have managed the feat of staying relevant, while holding firmly to the labor-intensive, hand-made excellence of their core business, which is so often lost in the modern age. Today, this is being fronted by Manufacturing Director Mick White, whose previous background saw him working for global progressives in aerospace engineering — SpaceX. This mix of knowledge between cutting-edge technological advancements and old-world skills is rather unique, and it offers an exciting future for the company.

The investment in their apprentice program must be applauded, and is a clear marker for their confidence in the future of all forms of hunting. Continued expansion has seen major improvements in their shooting- ground facilities, and as I can attest to, they employ some of the best instructors in the country. Never have I learned so much, or indeed shot so well during a clay lesson. A continued vision for innovation has also seen the company build a purpose-made, driven game simulator within the grounds, the only live firing facility in the country as it stands. An incredibly realistic training tool, it allows hunters to practice and hone driven shooting skills in a way not previously possible outside of mainland Europe.

Having been immersed in the Holland & Holland experience for just one day, I am filled with a renewed optimism about the industry. It would be a dream to one day add a Holland & Holland to my own gun cabinet, but for now I am content with the opportunity to share their history, heritage and vision for the future. There is no question that the company’s history makes for a fascinating read, but beyond this, the artform of gunmaking they’ve perfected is something which can surely be appreciated by everyone.