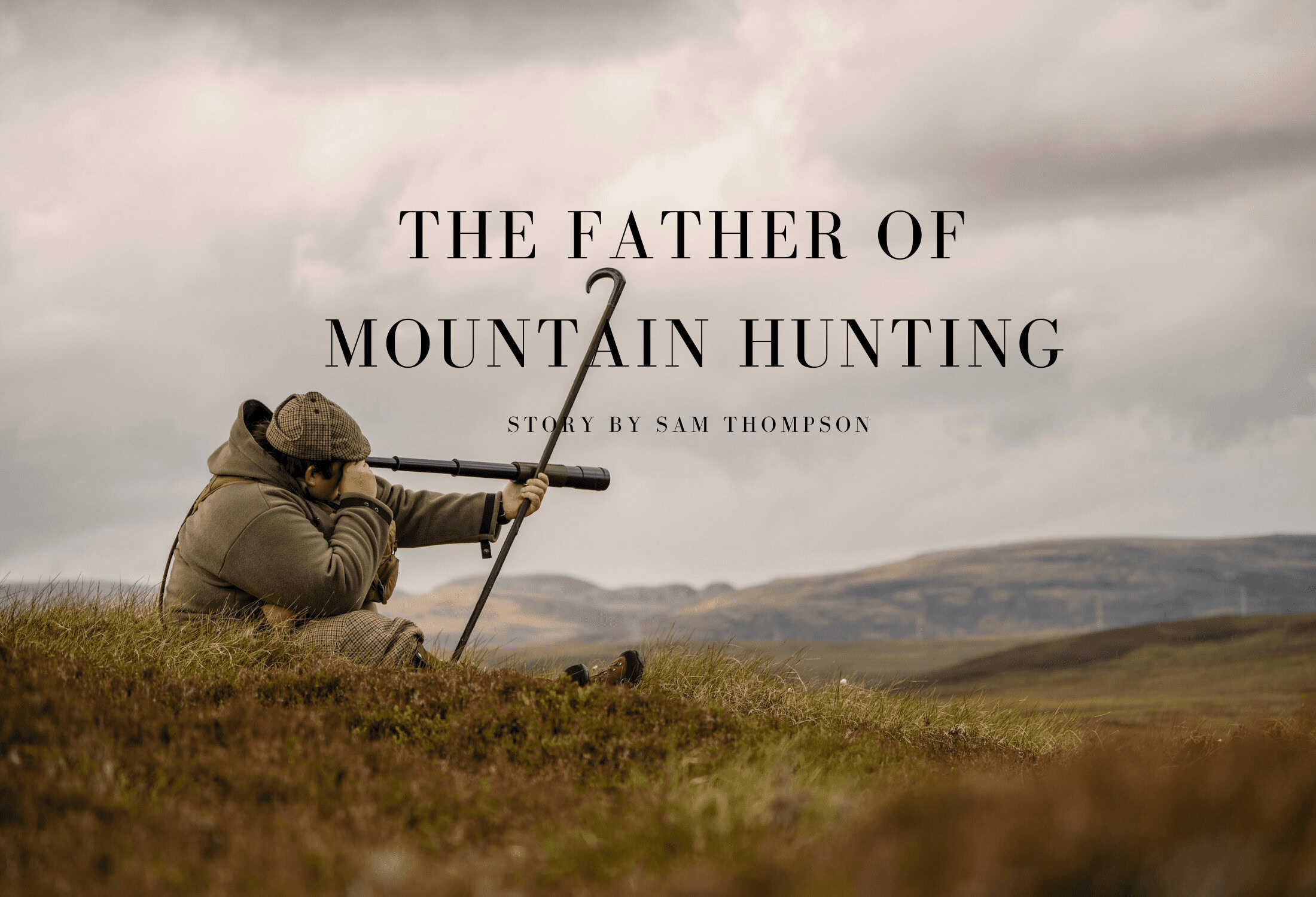

SCOTLAND | 1772-1852

“William Scrope (1772 – 1852) was an English sportsman and amateur artist, known as a writer on sports…”

As far as Wikipedia introductions go, I find that a modest one. The whole article totals less than 300 words, and mentions nowhere that this man probably played a more important role in creating opportunities for hunting in wild places than anyone else in history.

William Scrope avidly fished for salmon on the famous River Tweed in the borders of Scotland, and while he was there, became friends with a number of notable Scotsmen including Sir Walter Scott, the acclaimed novelist and poet. His time in esteemed literary company, and a passion for salmon, spawned his first book, Days and Nights of Salmon Fishing in the Tweed. Highland Scotland at this time had a very different relationship with and standing in the world than it does now, still recovering from the 1745 Jacobite uprising, where Highland clans rallied behind the exiled Stuart Royal family. While we know that Scrope was a keen sportsman of all kinds, enjoying fox hunting and bird shooting, there are no records as to what drove him to try his hand at deer stalking, which at the time was practiced mostly by local men and the few Highland lairds that still resided in Scotland — little more than a food-gathering exercise. In the late 18th century and well into the early 19th, the land north of Edinburgh was seen as the frontier of the civilized world, in much the same way as Western America. Scrope was keen for adventure as well as recreation.

Image used with permission from Euan MacDonaldHe arrived in a landscape scarred by the Highland Clearances, where large numbers of Gaels had been evicted from their homes (generally to coastal