Your cart is empty

We walk behind our dog as he works into the wind. I shift the shotgun to my other hand to rest my grip and relax my hinges, and I find myself wondering what it might be like to carry an old gun — a true heirloom broken open over my shoulder, nicked up and notched, splendiferously engraved, heavy with legends and legacy, punchy with recoil.

I wonder what it’s like to possess a wall tent that has dutifully kept the weather off generations of family. I wonder what it might be like to slip my arms into a heavy-weight, century-old wool coat laced with the dwindling scent of snow falling at first light. I wonder what it’s like to grow up with rites of passage that revolve around weapons and food. I reflect on what it might be like to be a young kid given a set of ground rules to accompany an Ithaca model 37 with which to studiously pepper the covey of quail on the gravel driveway that leads from the family ranch out into open space.

I’m growing maudlin, as I hike behind my dog, over all the antiquated hunting-related apparatus I don’t possess. Tools seem to be the face of tradition, the memories we can reach out and touch, the objects we press our faith into, the source of some superstition and luck. It’s by using a tool of the hunting trade that we imbue it with story, purpose, history and worth. There’s no mistaking it — I wear my lovely, covetous heart on my flannel sleeve. I wish we had old family hunting heirlooms, a sense of tradition that has been passed down to us. Alas, my husband and I have arrived in the world of hunting like squalling orphans left on a cold doorstep; we must find our own way.

We keep walking. The wind has picked up and the grass is groveling. The dog is working the air on the canyon rim now, and he pauses to gaze out at a sea of volcanic rubble before he follows his nose straight into hell. My husband and I exchange looks as we make our way down what we have termed a “chukar chute,” a gap in the rimrock that allows bird traffic to run upslope to the sage flats that flank the canyon. We came here the first time, long ago, by errant curiosity — which is how we arrive on the edges of most of the canyons we hunt. Our knowledge of land is slow to manifest and is the simple result of exploring time and space. As we learn and build a catalogue of information and understanding of the territories and animals we hunt, we’ve realized the greatest tradition to decorate family trees rooted in hunting legacy is the tradition of knowledge — knowledge of tools, weapons, land, seasons, animal behavior, and animal habitat. This trove of knowledge spans generations for some families and is what we envy most as hunting orphans. Instead of being lucky enough to learn by genealogical transmission and cultural immersion, we learn what we know by making mistakes, by stumbling into success, by carrying lessons forward with grit and grace and stubbornness. There is something tinier and older at work in us, too. It lies sleeping in our cells, in the coils of our DNA, so that learning is sometimes more like waking and remembering after generations of deep sleep.

“Young guns don’t stay young for long when they’re used regularly and earnestly. We tend to forget that all great things have small beginnings, and traditions are simply the wonderful consequences of heeding an ancient call.”

The dog is pointing in a steep field of basalt debris. Boulders the size of basketballs, cars, and modest off-grid cabins lie stacked and wedged as far as I can see. I begin my traverse. The angle of repose sets rocks to teetering, and I wobble as quickly as I can across the slope. I scramble up and over and through while I try to keep my gun ready in my hands. When the chukar flush, I pick a bird, swing through, and pull the trigger as black rock shifts beneath my feet. The bird falls, and I fall too, having planted my boots on untrustworthy stone. I’m a tangle of elbows and knees; an ache flares in my hip where thinly clad bone met basalt. I laugh because it’s more admirable to have a sense of humor than to cry, and I sort myself out. When I stand up, the dog is bringing a dead bird to me, and as I look down, I see a new, deep scratch in the stock of my gun. I feel a buzz of annoyance, and then I let it go. This is a young gun with many years of work ahead of it, and it’s better to think about what a pleasure it will be to grow old with it in my hands here in the canyons with a lifetime of hard-working dogs. I don’t want to be too precious about an inanimate tool that is intended to be my workhorse in the field. It’s a scratch. It’s a scratch that gave my dog a bird.

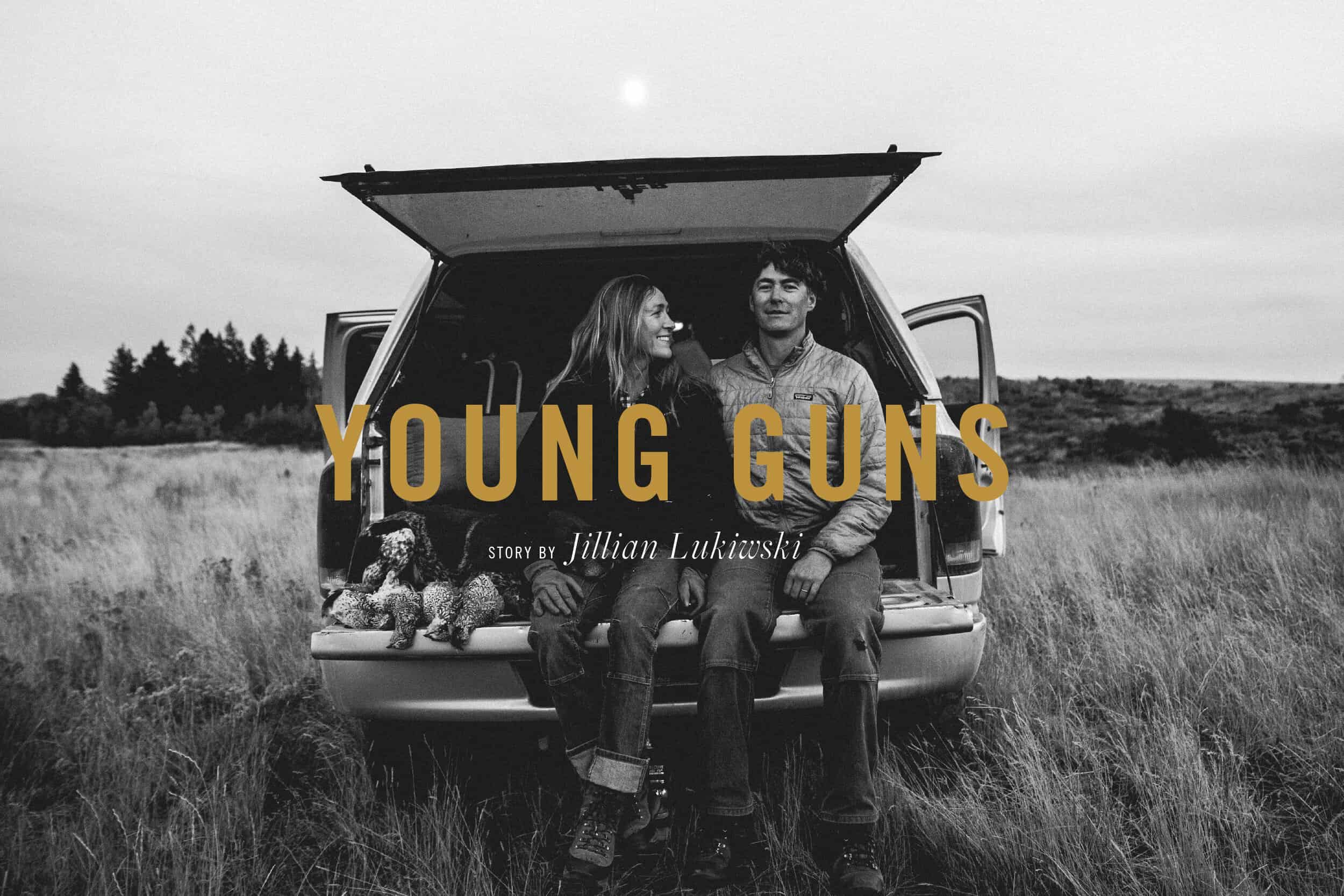

We arrive back at the truck as the world is turning golden. I toss my gear in the cab and look out at the sunset as the dog flops down in the grass and guzzles water. I decide it would be nice to come into this beautiful world on the receiving end of a family legacy, to be blessed with a birthright of knowledge, and to carry an old gun. But I’m able to recognize what an honor it is to carry a young gun, too. Young guns don’t stay young for long when they’re used regularly and earnestly. We tend to forget that all great things have small beginnings, and traditions are simply the wonderful consequences of heeding an ancient call.

Related Stories

Latest Stories