Your cart is empty

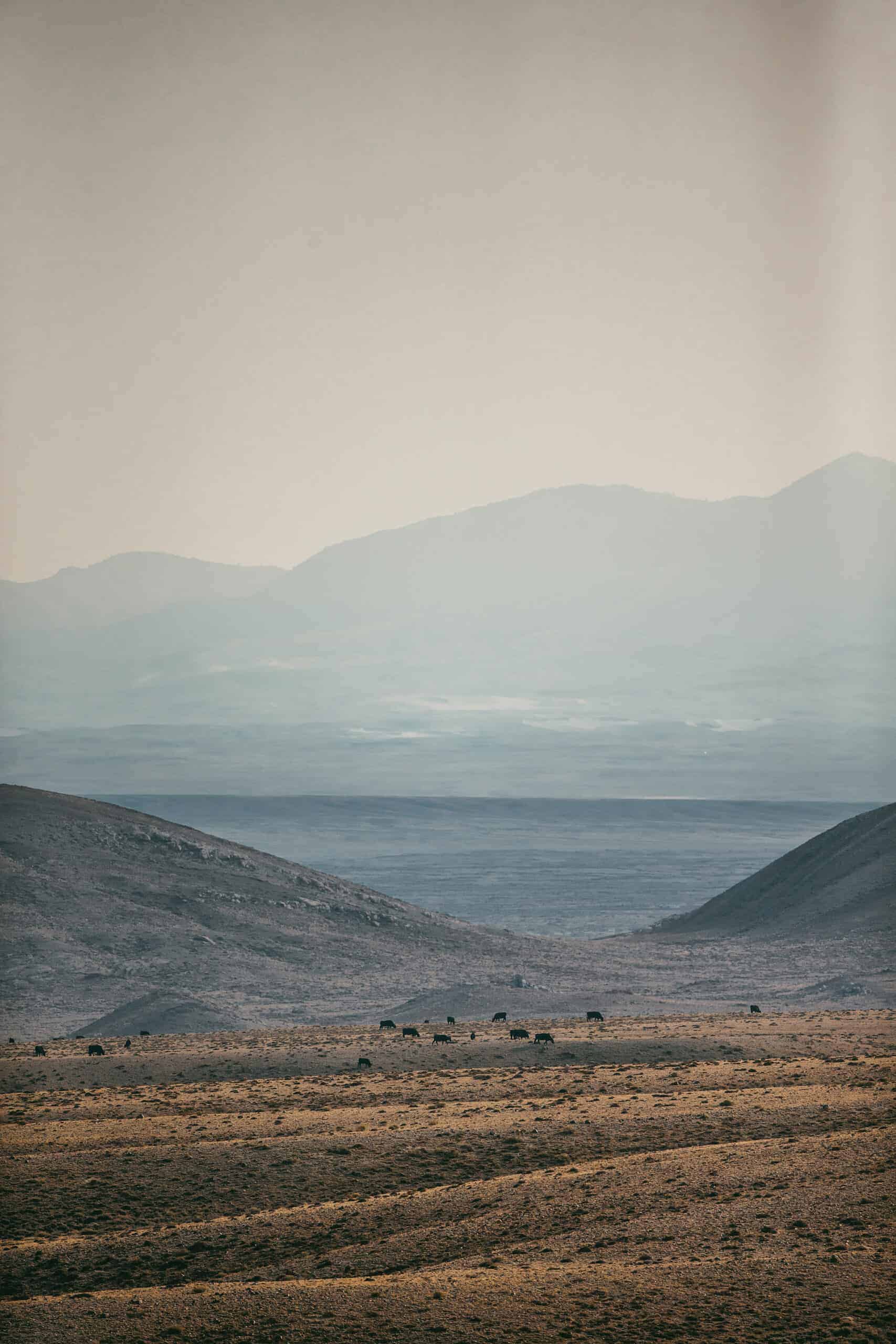

On the face of it, fattening up cattle on grass in the Red Desert of southern Wyoming looks like squeezing nectar from dried wildflowers – possible, though unlikely. But if you take one square yard of the sagebrush steppe and really stop to look, you’ll find forage that has been supporting megafauna for millennia. Wildland shrubs create a canopy that fosters a mosaic of lichen. Each color marks the bedrock of varied geology on which this steppe has grown. The texture of this landscape cannot be described in words but instead a feeling. There is a starkness in this landscape, found more in what is not there than what is. If it weren’t for the intermittent buzz of dirt bikes, it would be hard to place the time in history.

Mark Carter grew up in the cowboy country of the Red Desert, as a third-generation son of a rancher. If you ask Mark to tell you what’s hard about a cattleman’s life, he gives a youthful but weathered grimace. “We grew up gnarly, around livestock and motorcycles, and horses bucking us off. My dad wasn’t like, ‘How are your feelings today?’ He just said, ‘This is what we’re doing. The nights may be yours, but the days are mine.’ That’s what he always cold us.”

The ranching life is woven into the Americana fabric that defines the West, but cowboys are a dying breed. The consolidation of the beef industry has cornered many producers into a system of feedlot operations driven by commodity races that are at the whim of global markets. For the ranchers that make up the Ten Sleep, Wyoming-based Carter Country Meats, leaning into the headwind has become a stubborn mission, if not a way of life. Between the three Carter men – Rich and, Mark’s father and his older brother, RC – cracking the commodity puzzle has lit a fire so bright that it’s hard not to be drawn in.

To understand the origin of the cow boy, we first need to recognize the role of predators, like coyotes, wolves and cougars, that managed these grasslands before human intervention. Their presence pushed large ruminants across the land scape and created movement that the herd would not have made on their own. The Red Desert holds the largest unfenced area in the continental United States, providing open range for the greatest pronghorn migration south of the Canadian border. Mark sees the role he plays as an agent of environmental pressure on their cattle as part of the flow of the grassland ecosystem. “It’s natural for animals to be on chis land, it’s healthy, and it’s just as natural for us to be behind them, chasing them.”

The drier the environment, the greater acreage a rancher needs to graze their livestock. The Carters both own and rent rangeland across Wyoming. On a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lease that augments the family’s home ranch four hours to the north, Mark and RC push a herd of cow-calf pairs through Bull Springs, a perennial water source that bisects the Continental Divide. Though this natural spring sits at just under 7,000 feet above sea level, the water that percolates up from the bedrock will never flow off toward the Atlantic or the Pacific oceans. The Continental Divide Basin holds groundwater and melted snowpack in place, supporting forages like sale sage, Indian rice grass, squirrel tail and grey horsebrush for the Career Country Meats Angus beef herd. In an agricultural climate where the pressure of continually ratcheting up productivity is commonplace, RC stands behind his need to adapt the herd size to the status of the forage from year to year. “The stocking densities here in this country are a lot lighter than up in Ten Sleep just because it’s re ally sandy soil, so it doesn’t hold as much moisture. Bue on this lease, which is about 340 square miles, I think there’s probably 2,000 animals on it, depending on the year. On good years, when it rains, the forage would maintain even more than that.”

Desertification of land is hard to reverse in high desert ecosystems. The Carter sons learned early on from their father that it’s the job of the rancher to be a steward of rangeland balance. In the vastness of the Red Desert, BLM land is surveyed using lines on a map, not necessarily accounting for natural features that influence the viability of individual pastures. But the value of securing a lease and becoming a student of the terrain is not only smart business for the rancher, but an act of conservation in the greater picture of regenerative outcomes. Understanding what areas are most sensitive to erosion and where animals can access water requires an intimate sensitivity of the rancher with his rangeland. Mark points to several areas across the horizon. “All these wells are solar wells. My dad put these in when he first got chis lease, so he has water all over.”

Richard’s commitment to developing the desert pasture took an investment in time that unfolds much more slowly than grazing systems in regions with more precipitation. RC points out that many BLM programs are not nuanced enough to ac count for individual microclimates, but it all comes down to relationships. “You got to have the right BLM agent who is eager enough to look outside the box a little bit. We are working on some stuff with our range gal right now to go in and redo all the fences based off of topography. We look where the water’s at, the soil quality, and where we’ve got a bunch of canyons, rather than build a fence where it doesn’t make sense.”

Weathering the sand, rock and desert scrub on horseback is a longstanding tradition of the cowboy life, but Richard Carter realized decades ago that he could cover far more ground on a dirt bike. Mark remembers how his father put innovation in front of folk rituals to get the job done. “We grew up on horses. It was the standard-issue Western way. Dad, he’s still all about the horses, but just out of functionality, for being short-handed in big country with lots of cattle, that’s when we added motor bikes into the mix. I think the first time I ever chased cows on a motorcycle I was in the fifth grade. You can put in 100 miles a day on a bike. You just can’t do that on a horse.” Ripping through the desert on a motorbike may seem at odds with cowboy culture, but innovation is what has allowed Carter Country Meats to thrive with a nimble team. Richard’s roundup strategy now utilizes dirt bikes for their speed and efficiency in covering rough terrain while horses still offer the holistic proximity needed to be close to the herd as it moves across the range. RC’s wife, Annia, and their three sons, are all skilled cowboys and play a vital role in the ranch operations.

Mark’s scrappy childhood, driving cattle and running a ranch alongside his dad and brother, created a hardened approach in other areas of his life. Many people know Mark more for his career as a pro snowboarder than for the work he does pushing big animals through the high desert. ”I’m a rancher in the summer and then I’m a snowboarder in the winter. It’s all just navigating the natural environment and it’s very intuitive for me to just be outside all day. This is what I’ve been doing my whole life. I didn’t have the best snowboarding gear growing up, and I’m used to being cold on a horse, but that was good because then I just learn how to tough it out. There’s no bad weather, just weak people.”

The worlds of adventure sports and food production seem to be at opposite ends of the spectrum, but living his split life has made Mark stronger in both disciplines. “There’s a lot of overlap. With ranching, we were just taught that there’s no quitting. You just got to find a solution no matter what the job is. Then, in snowboarding, I take that same mentality into it. I’m a glutton for punishment; I don’t mind suffering one bit.” Mark started his snowboarding career later than most kids making a life out of the sport, but he quickly moved up the ranks to land coveted top-tier sponsorships. Now, he travels the world in between grazing seasons. “They’re different careers, but I would say being a snowboarder is a lot easier than being a rancher because I get to choose to go out on the days that I want, and it’s tough, it can be dangerous, but I know what the ranchers are doing, and I think, ‘this ain’t that hard.’”

Growing beef and selling beef are two different things. The Carters have worked for years to stay in the regional supply chain. Buying into the grass-fed ideal comes at a high cost, though. Restaurants and grocery stores don’t usually align their money with their projected values, outwardly aligning with local food sourcing, but not usually showing up for small-scale producers. RC knows that competing against volume producers is an uphill battle. “Everybody wants to stay local and grass-fed and feel good about themselves, but as soon as it comes to the money, they buy the cheap stuff. The whole system starts with corn and the big processing plants. It’s damn-near impossible to even compete with them.” In the current commodity landscape that incentivizes conventional corn production through taxpayer subsidies, more and more acres of farmland are being pulled into a monocropping system. Livestock feed has become a strategic link in the corn surplus that ultimately benefits seed-biocide monopolies, while extracting from the land and compromising the health of the humans and animals it feeds. But pushing into a market that is stacked against them has given the Carters even more determination. The brothers caught a break when they connected with a restaurant group that was drawn to their modern cowboy story. RC brought two cows into the sales meeting, and the product spoke for itself.

“They said, ‘We love it. How do we get more of this?’” RC recounted. “So we bought 80 cows from my dad and one of those overseas shipping containers for storage. We killed 80 cows and the restaurant guys are like, ‘We’ll take two a week.’ I’m like damn, finally, a home run, but then they only bought one cow a month. I was like, ‘We are in so much shit’. Because it’s worse than having a banker, when you borrow money from your dad. Every time he comes over, he’s like, ‘Hey, you got that money?’”

In March 2020, to reduce reliance on the grocers and restaurant accounts, Mark and RC launched a direct-to-consumer beef distribution program under the family ranch brand, Carter Country Meats. With the global beef machine creating an increasingly complex web of international trade, the Carters have put their stake in keeping their products as close to the source as possible. Mark feels that the ranchers who manage the animals and invest in the environmental viability of the land should hold the value of the product. “It’s just unfortunate that the ranchers, the guys that carry the animals their whole life, don’t get paid shit and the guys that hold onto it for two weeks get most of the money. We can all agree that nobody wants to see huge feedlots stuffed full of unhealthy animals, but then you come to places like this where you see these animals live better than most people. They get to live out here and just eat grass for their whole lives. That sounds pretty cool to me.”

RC sees that the system is stacked against his family’s ranch, but the solution, he says, lies in working outside of the system. “From the grass to the soil to the cows and then to the beef, the whole thing is not set up for a small rancher. The wholesale industry convinces the consumer what foods should cost, and for ranchers like us, we just can’t meet that.” RC and Mark see a path around the global wholesale marketplace through their direct relationships with their customers. RC’s vision is to take grass-fed beef out of the premium product category. “I don’t want to sell it to the 1%; everybody should be able to afford good food.” The bottleneck for the independent beef producer ultimately lies in the processing. Over the years, the commodity beef market has elbowed artisanal butchers out of rural communities, leaving small-scale ranchers with little choice for processing. RC explains: “It costs us a thousand dollars just to have them processed, but if I can do that on my ranch, then we can avoid sending them 500 miles to the closest processor, and then shipping that back. I have a skilled butcher that can add a couple hundred bucks to the quality of my meat. We can out-compete those guys, but it has to happen on a local level. Local is where it’s at.”

What Mark and RC are creating is a vertically integrated model that will bring back ranching traditions that have been reduced to relics of the West. Mark doesn’t want to romanticize the ranch life he was born into. “I don’t really care if people think I’m a cowboy or not. I just do the job and help my dad with what he needs. When it comes down to it, I don’t know more of a cowboy than him because he can do everything. You’re like a multi-tool, being able to get the job done. That’s a rancher.” The Carters’ commitment to conserving the Red Desert grassland ecosystem and rebuilding rural food systems is forged in a steadfast belief that traditional ranching is still a viable path. While raising and selling beef is stacked against the independent rancher, the Carter family is taking a traditional way of life and forging it into their own vision. Through their grit and tenacity, they have created a new frontier that returns to a way of life that existed before the business of beef was removed from the hands of the rancher.

Related Stories

Latest Stories