Your cart is empty

STORY BY Jean-François Lagrot

RUSSIA | CHUKOT

Six weeks in harsh harmony with the walruses and people of the Chukchi Country.

I’ve always thought that flying cannot be the same experience as traveling. Traveling is an immersion in an unfamiliar world, and the experience of its unveiling. If you fly 8,000 kilometers by plane to get to the end of the world, beyond the limit of what is known to you, both socially and geographically, then it is not you who arrives. It is only a part of yourself — your scout, an avatar. It takes time for your body to make physiological sense of your arrival, and more time for your mind to become fully aware of life as it unfolds. You slowly wake into the place of the earth where you’ve been projected. Harmony is only possible at this price, these days spent changing into a part of the new world.

I traveled for weeks toward the coast of the Chukchi Sea. Slowly, held back by the elements, by the wind, I followed increasingly uncertain connections eastward. I flew on six planes to get to these reaches, trailing farther away from human habitation with every stage. The entire trip from France lasted 14 days. I spent most of that waiting on weather and measuring in my head how this land near the Bering Strait was both the end of the world and a showcase of its origins. In Khabarovsk, where I made a 24-hour stopover, life still resembled what I knew in Europe, despite the presence of the exotic Amur River and an all-powerful, all-mysterious China on the other bank. The true shock took place during the next stage, as I ferried across the river to Anadyr, the provincial capital of the Easternmost Russian Okrug of Chukotka.

The water of the Anadyr River is as dark as the sky that overhangs it, the current is powerful, and the swirls have metallic reflections. The fast-running clouds over the town frayed on the edges of building blocks. Their looming silhouettes drew a chaotic line on the horizon. I had the feeling of entering a tenuous space, crushed between a leaden sky and a barely humanized nature. I entered a world I did not yet know.

August 2017: Maksim Chakilev is waiting for me at the airstrip in Anadyr. He’s a biologist, aged 30, calm and cheerful — but he barely speaks English. For my part, I only know a few words of Russian. Together, however, we are going to spend more than a month monitoring the migration of walruses in a small bay along Cape Serdtse-Kamen — the coast to the distant northwest of the Bering Strait. Here, herds of walruses come to call before crossing the Strait — a vital crossing that promises a winter in milder latitudes. A twin-prop Antonov 26 carries us to Lavrentiya, a village of a thousand ethnic Chukchi souls, where we sit and wait for one of the two Mi-8 helicopters that tour the Chukchi Coast to take off. Wind gusts ground us for a week.Enurmino, Nachkan, Uellen … Villages of a few hundred fishermen each streak along a hostile coast, either beaten by rainstorms or trapped by an onslaught of ice, depending on the season. They are accessible only by sled in winter, and by foot or helicopter in summer. By the time we can no longer believe it, one gray morning finally sees the legendary Mi-8 torn from the ground in an intense mechanical effort.

The machine is suffering. It lifts, barely, from the cracked tarmac, and we are finally free. We fly over rippling brown sandscapes and ocher wetlands, myriad streams and bogs divided into constellations and scattered islands of rock. It’s a desolate world apparently devoid of animal life. Maksim and I sit, silent in the helicopter’s rusted interior. In front of us, a Chukchi family, huddled together on the wooden benches, dozes despite the hellish noise of the rotor. The shaking slowly lulls our bodies into a strange apnea. I do not know what awaits me, but I already like this roughness, this nudity of the landscape, this monotonous tundra.

Maksim knows the bay we’re heading for well. Since 2011, he’s spent many summer months out on Serdtse-Kamen with some tens of thousands of walruses, a family of brown bears, and the occasional polar bear lost in the Arctic summer.The coast appears as a wire out of the gray light. Coal-colored waves advance toward the shore, sharpening into definition as they approach the beach, wanting to rip at banks of short vegetation battered by the wind. We lower next to two rows of wooden houses aligned along an artery of sand. The powerful heaving of the blades pins yellow grass to the tundra ground. A few years ago, another Mi-8 crashed at this very spot, amputating the village of many hunters and their families. The village of Enurmino brings together a community of around 300 Chukchi. The wooden houses built during the Soviet era have been the only human improvements to the landscape. Some of them lean dangerously. Some ethnic Russians live on the outskirts of the village, as if kept at a distance from land that is not quite their own. They are in charge of the power station that supplies the village. They also provide security, an undefined sort of policing that seems to be a reminder that this is still Russian land.A 30-year-old man named Stas is the head of the hunting community, and therefore the village chief. It is he who must lead us to the bay where we will stay, some 14 kilometers farther east.

In the meantime, he leads me to the container where the young hunters of the village stay. We smoke, drink coffee and tea without interruption, and chew on pieces of whale skin dipped in soy sauce. It’s firm but tasty, and it passes the time. We also cut thin slices of smoked whale tongue. Although I do not speak Russian or Chukchi, I understand from their facial expressions that the conversation of the young men revolves entirely around fishing and hunting. There’s a poster of the Cape’s salmon species on the wall, and they slowly argue over which type was spotted in a stream some days before. All have weathered cheeks, tanned by the wind and the cold. I can see that it’s this outer world, the world of animals, that defines them, through and through.

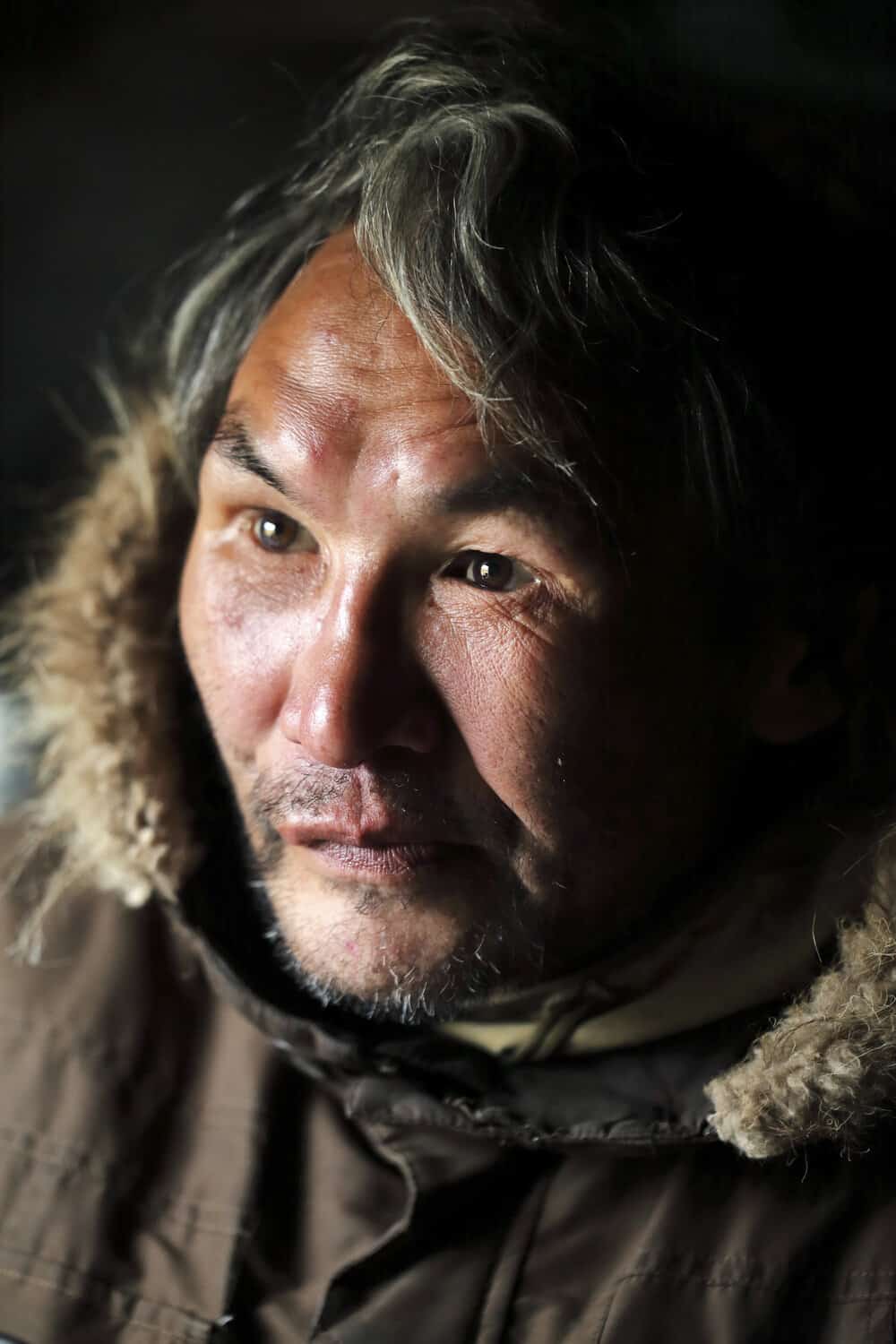

“The wind blows daily through the sandy streets. Every morning, the men go to the hunters’ house. The faces are coppery, large crevices define their features, and in their slanted and piercing eyes is reflected a large bay open on an unpredictable ocean, which, at any moment, can be unleashed with force.”

The wind blows daily through the sandy streets. Every morning, the men go to the hunters’ house. The faces are coppery, large crevices define their features, and in their slanted and piercing eyes is reflected a large bay open on an unpredictable ocean, which, at any moment, can be unleashed with force. They’re innately privy to this, and when the day of their hunt approaches, a crowd forms on the shoreline. All, with or without binoculars, scan the ocean. Far away on the horizon, fixing my gaze with attention, I spot a few plumes of flowing water that sparkle in a ray of whitish light. Morjare small groups of walruses that cross offshore toward Cape Serdtse Kamen, keeping close to the coast. They signal that the migration to the Bering Strait has started.

That morning, a spark runs through all the men’s laughing eyes. For each of them, hunting is a reason to live. But the sea is too rough for them to be able to launch their skiffs and head out on the water. They know too well the suddenness of storms that surprise this coast. They seem to wrestle with their instinct to go hunting as soon as possible, to accumulate as much meat as possible, to face the winter. We are at the beginning of September, and in two months the ice will appear, sounding the death knell for the short Arctic summer and the beginning of a forced inactivity which will not end until spring. They absolutely must take advantage of these two months to fill their quotas. Some 1,500 walruses can be hunted in the Chukotka quota, which must be distributed among all the coastal villages, with five whales given to the only village of Enurmino. Other men soon join them to watch from the dune. They’ve come back from a hunting trip in the tundra. Having left at 3 a.m., not long before arctic daybreak, they shot the first of the Canadian geese to have flown over the village this year. In days, there will be clouds of geese flying over the coast, heading south. The birds are no less a part of the food supply that will help the people survive the winter. Here, we are hunting to subsist.

We are hunting, in the truest way, to ensure the survival of the group. The women of the village spend days this season gathering berries — a precious source of vitamin C, from the tundra. They bring back baskets full, but still rarely enter into the houses of hunters. Certain tasks, however, are entrusted entirely upon them, particularly in the aftermath of a walrus hunt: they clean the tusks after they’ve been removed from the skulls, and boil the skulls to reduce the odor and refuse. The tusks are then thoroughly scraped and rid of flaps of flesh and bone, and are stored in a secure place before being sent to the administration for sale through a legal supply chain. Each man is indeed paid by the Chukotka regional government, as a hunter providing resources for the village, according to the amount of ivory he brings back.

Being allowed to accompany men on a hunting trip on the high seas is a guarantee of confidence. Stas makes me understand that he fears that my photos will backfire on them later. His lucidity surprises me. He knows that the walrus hunt can trigger outrage on social networks around the world, that the images will be stronger than the words that justify a subsistence hunt essential to the survival of the Chukchi. I promise not to betray their intentions and to do my best to convey this message. But what impresses me the most is this fair perception of these distant issues, his knowledge of controversies, of the criticisms of a detached and hyper-moralizing world, of the possible ravages of technology, and d beyond this knowledge, his own deep desire to protect an ancestral way of life. But I also know that though Stas made the deliberate choice to resist the consumer society and a more urban way of life, for many Chukchi, the temptation is great. Geographic isolation is then the last bulwark against acculturation and the loss of traditions.

The sea is flat, motionless. An endless mirror. There is not the slightest breath of wind as our four skiffs are distributed in the bay, moving away in opposite directions. These are the conditions we’ve needed. I have the privilege of being at the side of Stas, the most valiant hunter. Less than a mile from the coast, we spot a group of adults. They expel frail plumes of water at regular intervals, always moving close to the surface. In less than two minutes, Stas has reached the group. Equipped with a harpoon, the young hunter installed at the bow of the boat takes a last drag on his cigarette as if to gain strength; now he’s ready. Anticipating the appearance of a large male walrus on the surface, he readies his spear and, at its next jet, pierces the back of the animal with a powerful blow. The brownish mass immediately plunges, braked by the two buoys connected to the harpoon. Soon forced to rise to the surface to resume breathing, the walrus is struck again at its spine, fatally this time.

When the hunt is done, the tension released, Stas tells me the story of a hunter from Nachkan, some sixty kilometers away, who was killed by a whale he had harpooned. Diving to escape him, the whale’s monolithic tail struck him on the head, instantly breaking his spine. He died in that moment. I understand that here, one does not feel a condescending compassion for animal life — neither whales nor walruses nor seals — because everyone, animal and man, seeks only to survive. And survival is a fight that can also be lost. There is no malice in this hunt, no desire to wrest life. Instead, there is only the desire of living and bringing life to one’s own people. The death of this walrus is a gift. Hunters know its value. In the end there is a respect which needs neither words nor demonstrations. It is enough to have risked lives to receive it.

The boat has difficulty returning to the beach, imbalanced on one side by this inert mass of more than a ton. Riding under the straining power of the motor, it seems clear to me that calm weather is essential to undertake a hunting party: any wave could capsize the skiff. We have made the most of it, though. At the end of the day, eight adult walruses rest on the sand, their short fins folded along their bodies, their tusks each measuring almost a meter, their whiskers in brush. These animals seem to have come out of some fantastic bestiary. Out of the water, they look unreal to me. I linger to stare over them, curious and admiring.A heap of bleached whale vertebrae and a few rusty containers away from the dwellings mark the altar where the hunters will cut up their catch. It will take hours of cutting in the slow-freezing cold. All the men from the village rush to participate in the event. They pare back the skins and take the meat apart. Their gestures are sure and precise. They’re acting from and through a distant heritage — it can be felt.

“Every part of the walrus has its purpose. Organ meats are set aside for rapid consumption. Rid of the body and cut into quarters, the skin is folded back on itself then sewn into spherical bundles, trapping the meat, which will first ferment, then freeze in winter.”

Provocative, a hunter offers me a piece of raw brain. I taste it. It’s melting, it’s sweet. A powerful aphrodisiac, I’m told. Every part of the walrus has its purpose. Organ meats are set aside for rapid consumption. Rid of the body and cut into quarters, the skin is folded back on itself then sewn into spherical bundles, trapping the meat, which will first ferment, then freeze in winter. These are the kimgüts, bags of meat that are buried and later retrieved in the depths of the cold season. Today they are transported to the village by tractor and distributed. By the skinning grounds, on the outskirts of what now looks like a battlefield, dogs run and bark in all directions. A warm light passes. The cold is biting. Steam spirals from the sole thermos of tea. The hunters smoke. They are serene, happy with their day. I walk among them, hoping my presence does not disrupt their natural way of conduct. But they are kind to me, and proud to be what they are.

The next morning, the sea starts to churn. We must use the last few hours of relative calm to reach our final destination. We rush the boat out into the open water. Stas is concentrating. The Chukchi Sea leaves no respite. It changes in a snap without prediction. Men fear it every time they go out. No doubt they prefer it frozen, trapping them in winter, at least stable. The cliffs above us nest a colony of screeching puffins. Beyond Cape Serdtse Kamen, hunters can no longer chase walruses. That area is now protected. Maksim and I will venture there merely to observe and gather data on the migration. Our new home is a strip of sand with a lonely wooden isbouchkahut and the skeleton of a stranded barge.

After dropping Maksim and me onto the land, the boat leaves without delay. Stas will be back in a month. Maksim makes a silent thumbs-up parting gesture to the disappearing boat. He seems happy to find his hermitage. As far as the eye can see, the cliffs point east toward the Bering Strait. Sea birds swirl over the rock. We are now alone in the world, whatever happens, for a month. We drag our bag of potatoes, our canned goods and our generator to the isbouchka, what was once a hunter’s refuge. It contains two wooden benches, a table, and a stove. Our new life begins. Quickly, a ritual takes hold. Every day we must trek to fresh water. To reach it, we walk carefully between the remains of decaying walruses, all victims of trampling by their kin in the last migration. The coal heap, at least, is just a few steps from the isbouchka. It was the cargo of the barge that ran aground 10 years ago. We make use of this coincidence, digging through the black decay to find pieces that will best power the stove.

Throughout every day, our thoughts hang in anticipation of the wintry conditions that approach. A path runs along the beach then climbs among the rocks to the overlook of the bay. I look down to flocks of birds below that follow a gray whale, roaming the shallow water. The spectacle is fascinating.

“I feel like I have entered some alternate, virginal, unscarred world. One morning, we count up to 23 whales in the bay, feasting on krill. Over the month we watch walruses, whales and orcas in pursuit of younger walruses. On the ground, a family of brown bears comes every day at dusk to play on the other side of the lagoon.”

I feel like I have entered some alternate, virginal, unscarred world. One morning, we count up to 23 whales in the bay, feasting on krill. Over the month we watch walruses, whales and orcas in pursuit of younger walruses. On the ground, a family of brown bears comes every day at dusk to play on the other side of the lagoon. On the first evening they appear, Maksim fires a flare to announce our presence. He tells me that two years ago, he was sleeping in the cabin when a polar bear, attracted by the smell of cans, tried to get inside by leaning on the boards of the front door until it gave way. Panic-stricken, Maksim was able to chase him out, shouting like a beast himself. But I feel that this trauma is still present.Some days the wind is relentless; on these, I lie still, reading in the isbouchka. Maksim writes his daily reports into a logbook. Then, one day, we hear a knock on the door.

A stranger appears, traveling on the tundra nearly 150 kilometers, on foot, from the village of Lorino. His dog is his sole company. Having left nine days before, he had stopped only for a day to shelter from the rain under a rockpile. He followed the coast to keep his bearings. Aged about 50, Sergeï carries a wise and gentle look, as keenly intuitive as he is intelligent. In the rays of light that pierce through the single window of our cabin, his angular, tanned and asymmetrical face is a story in itself. We could read the life of a Chukchi hunter — his battles at sea, his epics in the blizzards, his wounds, his courage and his fears. Hungry, he devours everything we offer him: canned reindeer and salmon in broth. It’s normal that we give him everything we have. He’s not bothered — this is simply how men should be. But he is also not satiated. He doesn’t hesitate to go raise the fish net that we placed across the nearest stream. That day, luckily, two salmon weighing more than two kilos each are captive there, including a female full of eggs, which he prepares with salt. He speaks little, but I learn much from his presence alone.Sergeï spends two days with us, the time he needs to regain strength before leaving for Nachkan, still a distant 80 kilometers away. I see no tiredness, anxiety, or frustration in his eyes. He does not complain about a delay, nor the distance yet to travel, and he does not seem weighted nor concerned. He seems happy, to me. Each morning, we walk in the direction of the distant Cape, stopping from time to time to count the heads of the seething mass of walruses, which, day after day, piles deeper out into the bay. At the beginning of September their number increases slowly. But soon they begin to take possession of the rocks, climbing over each other until the smallest accessible plot at the foot of the cliffs is occupied. Their cry, something like the bellowing of the cow or the grunt of the hippopotamus, resounds along the walls while their acrid smell reaches us in asphyxiating puffs. At the slightest wind storm, though, they flow back to the sea where they feel more secure.

In the days that follow a wind surge, the whole swarm mysteriously disappears. We wait, each time, to see their numbers surge again.In the evening, around the stove, Maksim and I take the time to share our stories and our lives by interposed dictionary. We are friends, for in the present our aspirations are the same, our sorrows and our joys identical. Almost every day, a salmon caught in the morning complements our meals. We go to gather berries. The days go by peacefully, without surprise. Increasingly numerous and raucous groups of walruses are now invading the bay. Soon there are several thousand. I descend into the cliffs and spend hours observing them, fascinated by the morphological differences that exist from one individual to another, both in terms of body size, color and contours of the skin. Their uniquely whiskered faces make them recognizable personalities at first glance. They’re not the anonymous clones that I’d imagined from a distance. Their close proximity, the folds of their flanks with reflections sometimes bronze in color, sometimes copper, all combine to make their colony a monumental work of art, a painting in pastel shades posed in a decor reminiscent of old engravings. They gather, all lit by dramatic, glinting light.Soon, winter makes its first tracks. The humidity becomes more penetrating. A film of frost covers the sand in the early morning, and groups of increasingly large walruses play with the rollers that run up the beach. It’s like they’re waiting for a mysterious signal to invade.

On September 26, 2017, the day before my departure, I wake up slowly, and a deafening chatter reaches me through the boards. In the tundra burned by the wind and the cold, large white flakes cover the gentle slopes that rise toward the summits. But it isn’t snowing. Thousands of geese have stopped in this bay they thought was deserted. The show is of great poetry. Each of them, wings folded, looks like a delicate flower blooming on the tundra. The wind has died down after the storm of the past few days. Following to enjoy the spectacle, Maksim, leaning on the door frame, beckons me to look on the other side, to the end of the beach. After sweeping the strip of sand from one end to the other, my eyes widen… A colony of walruses has taken possession of the entire shoreline, so camouflaged in its magenta-brown tones that it is difficult to distinguish at first glance. Although there are more than a thousand, Maksim also did not spot them at first.

The day before my departure, like a playful wink, the walruses arrive in full, the absolution of their massed voyage to this bay. Maksim then curiously consults his notebook. The previous year, the walruses had hoisted themselves onto the sand on September 26.The first hours spent in this bay come to mind as I climb alone on the tundra. When I arrived, this environment from the cliffs to the lagoon seemed incredibly hostile. Today, I regretfully leave this simple and powerful moor. I only passed through. I like to think that tomorrow the wind will blow again, the cold will become more pungent and walruses will always pile up higher on the sand. When I reach the pass, I turn to search the immutable landscape. Nothing seems to be able to disturb the fullness that reigns from one end of the bay to the other. Maksim’s silhouette stands out on the sand. The walrus colony has once again collected in its inseparable, unchallengeable mass. I never imagined that my gaze on these animals of another age would be so transformed by this experience. I never would have thought that the fate of this animal, and that of the Chukchi and of this bare, rough and magnificent land, could all be so beautifully entangled. As I am to depart on this last day, I feel in myself a pain of detachment from the great network I’d slowly come to be a part of.