Hereford refused to let the grass grow under his feet. He quickly amassed the technical acumen needed to be an expert, and pairing that with a preternatural instinct for storytelling, he defined his style through surly honesty and sharp shots. It was right around that time that Maggie Kennedy, my photo director at Garden & Gun magazine, first brought him to my attention.

It didn’t take us more than a minute to decide to dispatch him to Birmingham, Alabama, to photograph legendary Southern chef Frank Stitt. The results were iconic, and minutes after they landed on my desk, my phone was in hand and William was obliging every curiosity. He told me about his passion for fly-fishing and how the outdoor sporting life had been baked into him at an early age by his grandfather Frank L. Hereford Jr., the former president of the University of Virginia. We talked about his brothers’ restaurants and how nature and food have influenced him. Since then, I’ve sent him on shoots all over the world, from fishing in the Slovenian Alps to walking onto a fashion set at Po Monkey’s juke joint in the middle of the Mississippi Delta, to fixing his camera’s gaze upon bluesmen Cedric Burnside and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram before paddling around the Everglades with iconic outdoorsman Flip Pallot.

Vanity Fair, Travel + Leisure, Conde Nast Traveler, Departures, Food & Wine and Bon Appétit all led to some cherry assignments in the commercial space with brands like LL Bean, Tom Beckbe and Le Creuset (to name a few). After pulling together a career that would be the envy of many a shooter, Hereford — at the top of his game, no less — decided to walk away. Or perhaps not away, but rather toward.

See, in a world rife with social media plasticity, AI-generated “photography” and overly wrought and directed commercial shoots, Hereford quite simply had had enough. He knew it the moment he landed in Uruguay.

There, while on assignment to photograph Frances Mallman’s cookbook, Green Fire, Hereford felt a peace he hadn’t known for a good long while. The experience of seeing Mallman, one of the world’s greatest chefs, thriving in a town with a mere population of 200 transformed him. It tightened the aperture. He reassessed his own value system and in due course hit the reset button, hard.

They say the eye has to travel. And Hereford’s got the sky miles to prove that his eyes have. But once folded into the beauty of the southern hemisphere’s uncanny natural light and lazy breezes, Hereford knew there’d be no going back. Because he could see a way forward, something he finally wanted to work toward.

Today, aside from the occasional cherry-picked assignment, Hereford spends his time in the tiny pueblo of Garzon in Uruguay with his wife Nicolette and their daughter Edda. He leads photography workshops from a handsome and inspired studio space that they built, sits with the neighbors wrangling horses and crafts images made from good old-fashioned large-format analog cameras. And that’s where we caught up to him, fresh out of the dark room he’s building in the backyard, where he’s learned the native language and settled into a vibe that’s far more rhythmic than algorithmic. Less augmented, more deliberate. We should all be so lucky.

So who put the camera in your hand first?

William Hereford:

It started with an obsession with gear as a young kid. I picked up the family camcorder and used it all the time. And then I went to college and I was a history major and my girlfriend, my senior year, got a camera for Christmas, and suddenly it was in my hands again.

I didn’t really understand that there was a photographic industry. I kind of thought that all photographers were artists and they shot for money when they had to. So my love was just because I really enjoyed taking photographs.

Shortly thereafter, it became a business and I worked very hard at it, as one does. And in the last two years, I’ve transitioned away from it being a business and have really picked back up where I started in at the age of, you know, 19, 20 … with a mindset toward making [fine] art.

MM:

This muse who put the camera in your hand, are you guys still friends?

WH:

We’re very good friends. Alyssa Pagano, she was the first person in my life that showed me that you could create art for the sake of creating art. We were both interested in Andy Goldworthy, and he was making art that fell to pieces, you know, ice sculptures in nature.

So we would do things like go out into fields and create traces of each other’s bodies lying in the grass with leaves and wood.

She kind of brought the camera back into my life. And I started photographing the things that we were doing. And then that led to a career in photography.

MM:

Back when we were making art and not “creating content.” Do you remember, was there one image you caught where you were like, “holy shit, I could do this for a living?”

WH:

Well, and that’s a good question. There wasn’t a single image.

MM:

It was just a feeling?

WH:

No, I made a viral video, and that helped me launch my career. It was right around the first iPad, and the virality of that video led to a commercial client that led to money. And then I had the time I needed to become a professional photographer. But I think what you’re really asking me is, where did I get the confidence to believe I could do it?

Because in 2007, when I entered this industry, we were on the edge of the Great Recession. And there I was living in New York City and there was chit-chat about the New York Times shutting down, banking systems collapsing and such. Going into a creative profession at that time probably wasn’t the best thing you could do.

I don’t know how and when I crossed that line, because when I got out of college, I thought, “Oh I’ll be a lawyer or I’ll work in some mid-level finance job,” because my father had often struggled with money, so I was very motivated to make money. But as soon as I was out in the world, I got really scared of how much time I had. Granted, I had a ton of time. But it just became obvious to me entering the workforce at the age of 23 that you have to do your job a lot of hours per week. So if I ended up someplace miserable, I was going to have a miserable life, you know? I was very afraid of that, and that helped me follow my creative interests professionally.

In a way, that goes back to that camcorder you were running around with as a kid.

WH:

Yeah, and I was a photo assistant at the time when video was coming into the photographic industry, so I was shooting video the way that a still photographer would shoot stills — putting the camera on a tripod.

I could get jobs as a videographer quite easily. But what I really wanted to do was be a photographer. And so I shot video like a photographer composing graphic shots.

And then lo and behold, we had an iPad and an iPhone and we were looking at screens, and textual overlay on moving images is commonplace now, but at that time, it was a really weird, interesting thing to do. The viral video I made was just that style, with food. Seemingly simple now, but at the time it was quite novel.

MM:

Kind of cool that you’re a lensman trapped in the body of a cinematographer.

WH:

I would say that I was always meant to be a photographer. And at that time, I was doing whatever I could do to be a photographer.

MM:

That’s a fun time in a career — and in life — when you’re young and what you lack in experience, you try to make up for in aptitude and pure hustle. And you’re just sort of running around talking and trying to flip a buck, trying to sort of figure out what the universe is trying to tell you it wants you to be.

WH:

Yeah, in your 20s, you’re into top gear and trying to become important. I mean, of course, there are plenty of exceptions, but at least me and the people I was rolling with, we were seeking traditional avenues for self-worth through magazine accolades and assignments.

MM:

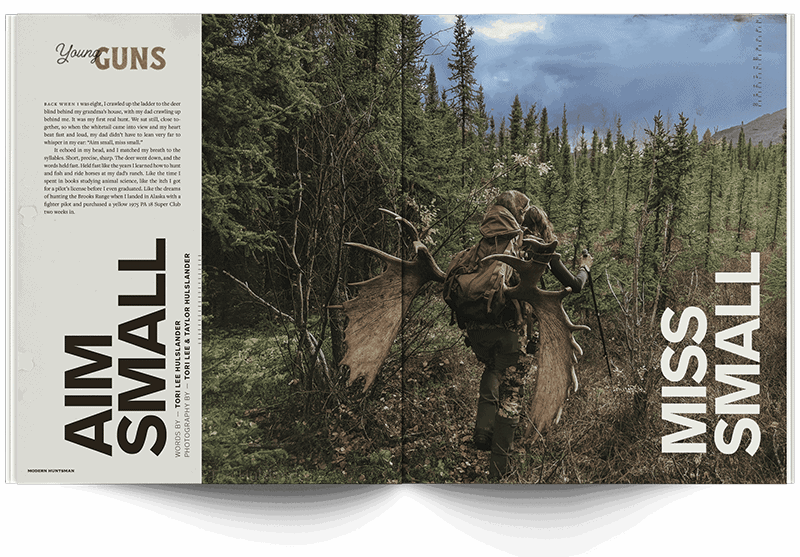

What was the first thing you shot that started moving your career toward the work that’s really defined where you are today?

WH:

It was at Frank’s. It was a portrait series.

MM That portrait you got of Frank, for Garden & Gun, I thought was one of the best photographs we took the chance to run that whole year. It was so stoic and artfully done. It was perfectly balanced. It was textural and lit to perfection.

When I saw that one, I thought, wow, that’s going to be the one that sort of hangs as an homage to one of the greatest Southern chefs that’s ever existed. At that point, had you already shot a lot of food photography as well?

WH:

So that viral video was a recipe video. It was about how to cook a duck breast. From there, I started getting food clients.

And at first I felt like I was above that, because I had traveled the world with fashion photographers and I fancied myself a graduate of that part of the industry.

But then I started finding work in food that I really loved. And so I did something that I think was very smart. I went and I found work that inspired me in that industry. Instead of feeling above it, I said to myself, this is where I am. This is what people are attracted to in terms of my skillset. And I started going back to old, old editions of Gourmet magazine and looking at all their covers and the great, late Romulus Janes, who died a few years ago.

These guys were shooting four-by-five film still, and they were doing creative editorial food work — like an Italian-themed dinner where they were casting the table with interesting older men and models.

MM:

It’s funny. I buy a Gourmet whenever I see old back issues at a yard sale or wherever. The photography is just unbelievable.

So when I think about pairings from an editorial perspective, I think about the photographer having command of their craft, but I also want to pair photographers that I know will get along with the subjects or have experience in what I’m sending them to capture. For example, I wouldn’t send a studio product shooter to capture a bunch of duck hunters in a Stuttgart, Arkansas, blind in the dead of winter. They wouldn’t fit in or speak the language.

You like to hunt and fish. Did you grow up hunting?

WH:

Yes, I grew up hunting and fishing.

MM:

I know that when you get to a shoot, 1) you’re going to blend in and make it fun for everyone; 2) you’re genuinely interested in the material you’re there to get; 3) I implicitly trust that you’re not going to, say, fish, until you know you’ve gotten the shots we need. Growing up a hunter and angler, who’s been fortunate enough to have their camera take them around the world, talk to me a little bit about that. What does that feel like? We’ve talked about fashion. We’ve talked about food. And you’re brilliant at both. But talk to me a little about the hunting and the fishing and where that fits in. Is it as captivating to you as those other subjects?

WH:

Well, yeah, I mean, fuck fashion. I don’t have a lot of interest in photographing fashion anymore. I find fashion to be interesting, sure. But only when someone’s really into it and they have something to say, then I’m very interested in their voice. Currently, I have no voice in the fashion industry. So if I’m doing it, it’s only to make money.

I would say that it was my grandfather who was a good old boy, a Louisiana man who moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, and taught me all that nature stuff when my father didn’t take to it. I’ve heard the saying many times that a love of something skips a generation.

I had a general interest in fly-fishing and hunting for birds. I fish and I hunt for birds still, but it’s photography that really helped me recognize how beautiful a way it is to live your life.

I go to Patagonia a couple times a year to fish for trout. But down here, I fish for Black Drum, and I’ve got a skiff there. And I might do some guiding here and there as time permits.

But when I fished every day, I was home in the Catskills. That was a few years back. And so when I moved down here [Uruguay], one of the agreements with my wife was that I could buy a skiff. A few hours north, I can fish for Dorado, Golden Dorado, and that’s a beautiful, big yellow fish.

You know, when I was thinking about this interview and what you might ask me, one thing I wanted to mention is that in English, we say “it’s a way to live your life” or “it’s a means to an end” maybe. But I don’t like that — you kind of imagine someone cutting through grass, like looking for a way through.

In Spanish, they say “form” instead of “means.” And I just thought about how I love that warm word because form, it’s something in between, like a blueprint and a way. So it’s like “I can find a form to do this” or “this is a form for living.”

And the thing about being an outdoorsman, about hunting and fishing and having a love for dogs and the seasons and the health of the environment, is that yes, I care about protecting those things and perpetuating those things into my daughter’s life and her children’s life. But more than anything, it’s a form for life. It’s a blueprint, a way to exist and be more connected to this great mystery, this great adventure we’re all on.

And so when I’m on those assignments, it’s hard to not recognize 1) how lucky I am to be doing it, and 2) that I found my form for living.

MM:

I know you have a curious spirit. You’ve traveled the world. And now you’ve settled in Uruguay. What are you excited to explore down that way? What’s turning you on? What are you excited to point your lens at?

WH:

No longer being a man of the world is what’s turning me on. I’m in a village with 200 year-round residents. This transition I’ve made is about being a part of a community. It’s about knowing, it’s about having a garden that doesn’t die.

It’s about knowing the phases of the moon, which sounds pretty hippie, but if you know what the moon’s going to look like that night, you’re probably pretty in touch with where you are. And it’s photographically about not going into a place and taking photos really quickly, but being a member of a place and being granted access to different worlds, different living rooms, different people, different conversations, learning the language well enough that I can communicate myself. This transition to Uruguay amongst other things is about becoming the artist that I was when I was 20 and didn’t know better. Letting go of a lot of the old hustle and making work that I live in as opposed to traveling someplace and taking work home with me.

MM:

Did hunting come first, or the food? How did one inform the other?

WH:

Professionally, the food came first and then the hunting came second. But the food led to portraits of the people making the food. And then that led to a great love of purveyors and produce and where the food came from. And then that led to the hunting.

MM:

You’re a father now, and I know you lost your father not too long ago, who was very dear to you. I’m sorry for that loss. Where does he fit into your maturation as a professional shooter? What are some of the lessons you garnered from him?

WH:

How do I say it? You know, from my grandfather, I really learned the structure of how I wanted to live, right? Financial responsibility, connection with nature, blah, blah.

MM:

Love of the land.

WH:

But my father, he was just like a beautiful tornado. You know, you could just look at him and you fell in love. Most people did very, very quickly. And as you got to know him, you realized that if you got too close, you might get sucked in. And so what I took from my father was how to appreciate and connect with people very quickly on a very real level. My father was kind of like a walking heart, whereas my grandfather was a World War II–era foot soldier, a closed-off scientific type. And so when I see kind of unbelievably strange things, it’s from my dad that I’ve come to see those happenings as beautiful — you know, two drunk guys hugging each other in a bar right before one of them throws up or a sweet couple on the back of a truck. My father shaped the way I find beauty in the nonlinear. As an artist, I just find that stuff to be intoxicating. I don’t have the guts to live the way he did, but I try to take that with me wherever I go, with whoever I’m talking to.

MM:

He played guitar, right?

WH:

Yeah, played guitar and taught me to play the guitar.

Is your mother an artist?

WH:

My mother’s a writer. A therapist and a writer.

I would say my mother taught me how to see beauty. Like when you see it, you know, the light on a tree or something. But my father taught me like, look how fucked that is.

MM:

Well, that’s one of the things I love about being on a shoot with you is that I feel like you’re always connecting with the people on the other end of the lens, the people who are the story.

I think that it takes a confidence that comes with time and experience. But it also comes from that deeper thing that I think maybe you get from your father and mother, probably, and grandfather, you know?

WH:

And that is usually a little intimidating and a little strange. I’ve always had a great deal of sensitivity for folks who get in front of my camera, because they’re naked, you know? I find people to be fascinating. But what I think you’re mentioning is I have a lot of empathy for just how intense an experience it can be to have your photographs taken.

MM:

I think everyone gets super self-conscious as soon as the lens is gazing at them. I’ve always noticed this from you, you just have this amazing ability to instill a confidence in them, to make the image feel found and natural, not forced. Even when it’s as stoic as that Frank Stitt image is, it feels very found to me. It feels like a very real moment.

WH:

That means a lot. Thank you. It’s like they become children, whether it’s an 80-year-old man or whatever, I just find myself saying things that I would say to a kid who’s going to get a shot at the doctor. It’s like, “Don’t worry. It’s almost over.”

MM:

They put so much of their faith in you to guide them on the journey through the process. You have an uncanny ability to find details. Say, to catch the 25-year-old fishing cap with all the flies stuck in it on the truck’s dashboard, the kind of artifact that sort of tells the story of the fisherman’s journey. The angler holding a bottle of hooch in the river. I really dig those kind of moments.

WH:

Yeah man. That was a really good day. I still think about that day.

MM:

You would post behind-the-scenes shots of some of these professional commercial gigs you’ve been on, which I know the orchestration behind all that is an absolute nightmare. And you probably felt like a cog in a big machine.

I have always thought about you as someone who can mine a moment but it never feels manufactured or faked.

I know that you’re happiest when you’re in your flannel or in your waders and the sun is shining bright and you’re making work that feeds your soul extemporaneously.

I feel like that quickens your pulse, but also sort of slows you down and connects you and grounds you.

And it comes through in the quality of the images you make. Can you speak to me a little bit about the terrain down there in Uruguay and how it’s inspiring you now? Is it evolving you, changing the way you shoot?

Yeah, that’s an awesome question. It’s very different than the Blue Ridge Mountains. I’m in a kind of Texas Hill country, but it’s green all year round. I’m in the southern hemisphere, so it gets colder as you go south. We’re in the northernmost region where you can still have palm trees.

I was already definitely on track to be a cabin-in-the-woods guy. And then fate brought me down here with a book. I shot a cookbook for a chef and met my wife and now we have a kid here.

Now I have to speak Spanish all day. It’s all a new terrain. I find myself falling in love with landscapes and the way the sky looks at certain times of the day and so on and so forth. It’s a grand adventure in the middle of your life to just fucking mix it up like this. It’s really scary, and I’m not saying everybody should move to a developing country. But what I am saying is that if and when you have the desire to just change your life, whether that’s getting out of a relationship or whatever, the experience of relearning to live at middle age, it will change your perspective on everything.

MM:

It sounds like a beautiful tornado. You threw caution to the wind.

WH:

It’s a place that inspires me visually.

I’m in this marathon period of my life now where I go slow, but I go every day because I love it. As opposed to money here, vacation, money there, visit parents, money here, weekend in New York City. Now every day is kind of the same. I’m moving slowly through it and I’m inspired.

MM:

You found your rhythm.

WH:

You can relate to this. I thought that I had my rhythm 10 years ago. When I shot a cover for Garden & Gun with my ex-wife on the cover, standing on top of a vintage Land Rover in Cumberland Island. I thought I had made it.

And it turns out I like this version of me. I’m not embarrassed, but this version of me has no interest in doing anything like that again.

MM:

Been there, seen it, done it. Youth had its day. We get our scars. We learn our lessons and we deepen and we mellow out.

Culturally, it’s so different down there. It’s new. Probably everywhere you look, your lens is finding something fresh and inspired.

You know, I saw your Malman book — Francis Malman, who’s a hero of mine as well. I like the way that man lives his life. He just said, I’m going to do it my way, exactly how I want to do it.

Has that relationship deepened since you’ve been down there? What role does he play in your new life now?

WH:

You know, I live in this little village, and Francis’s most famous restaurant is here. So it’s like going to Disney World, Francis is Mickey Mouse, and I just checked into a room.

Francis called me the day my father died. We had a conference call scheduled about his book.

I said, “Call me tomorrow, dude.” So he called me the next day. I had said what a fan I was, that I had seen his television shows and the Netflix documentary and seen his books. And he said, “William”— in his voice that causes you to straighten up, one that sort of booms — “I heard your father died.”

And I said, “Yes, it’s nice to meet you. Yeah, my father died.”

And he said, “My father’s dead too. You will be fine.”

And then we just moved into the business that needed doing. And what’s funny is between the time that we shot the first part of the book in Brooklyn (all the recipes), before I came down here to shoot, my ex-wife and I split up, and he was there for me then too.

He was there the moment my dad died and his father had just died. And then in the second trip, I was in Disney World with him, like in his castle. And we talked about divorce, and he happens to have had a few of them, you know, and I remember he said to me something like, “If you're able to, I would shut the door quietly.”

MM:

The bigger the love, the harder the split. Shut the door quietly, sage advice to be sure.

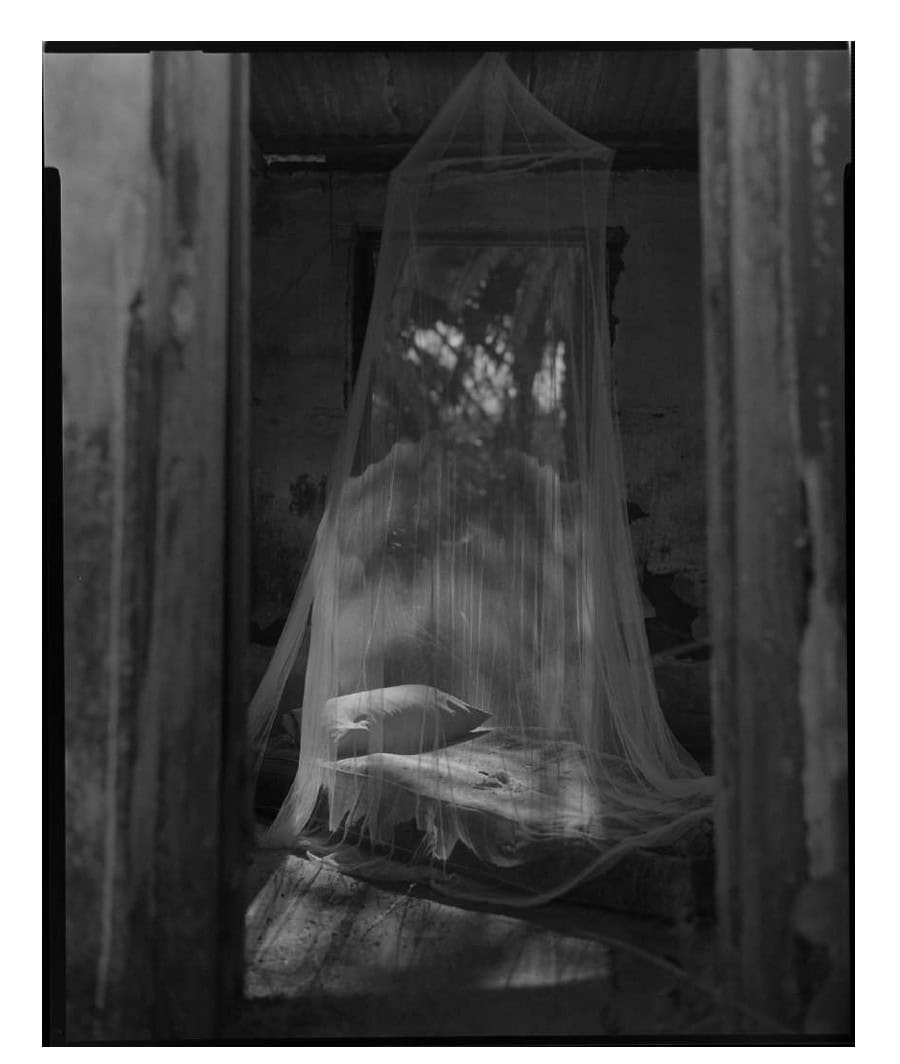

Do you have some personal projects you’re working on now, and can you tell us about them? The reason I ask is — keeping tabs on you from afar — I see your lens is focused on a particular building with a great patina.

There’s a bed in it with netting, and I can't tell what you’re doing with it, but I see there’s some sort of intention you’re trying to bring to it. A sort of examination.

WH:

I moved down here and do four photographic workshops a year where students and wine lovers and travelers with iPhones come down to our village here and have this kind of curated experience where I walk them through how to photograph travel stories.

But really, it’s about the experience of how you connect with the place you’re visiting. My doing this mainly stems from the fact that I did so much soulless commercial work and I got so fucking sick of those idiots in that space. You can print that.

I just love the idea of a woman in her 50s who comes from a religious background and is in a bar with a gaucho speaking three words of Spanish, or a middle-aged man who’s going through a divorce looking to talk about life and love and light and art. I just enjoy connecting with authentic people who are motivated to take better pictures.

It’s a really fulfilling experience for me. I’ve got my print sales, and have been fortunate enough to have the flexibility to tell all of these [commercial] people that are selling garbage stuff from China to go fuck themselves.

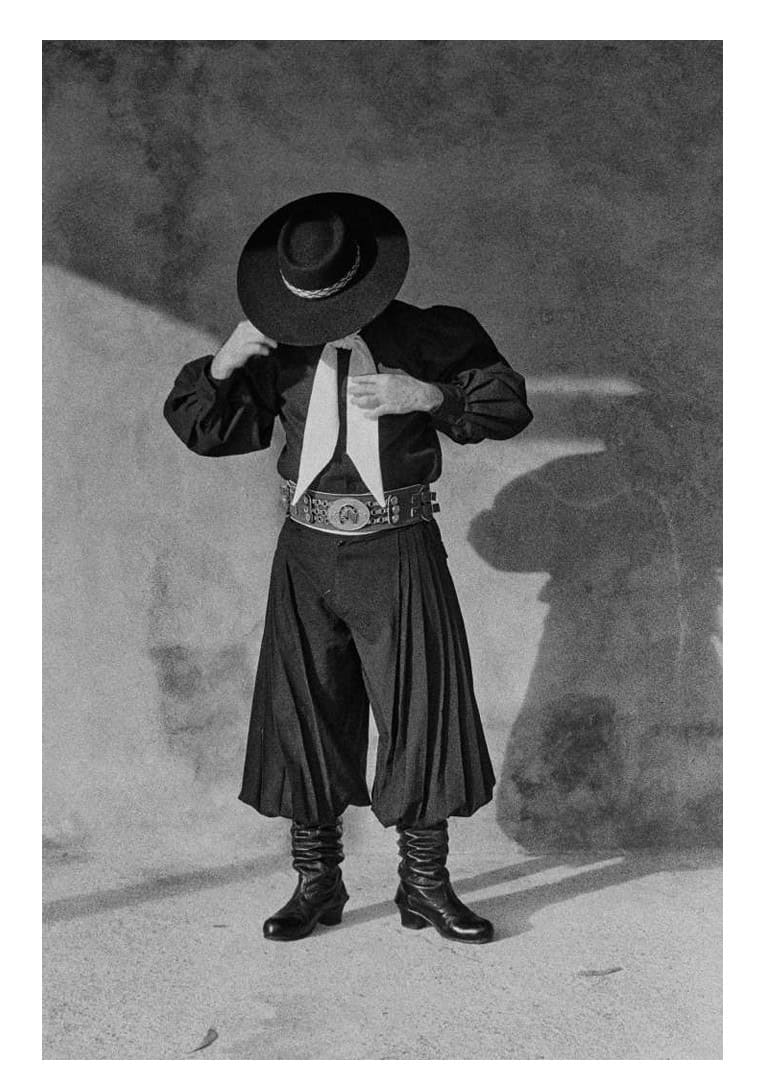

My agent is not very happy about it, but I’m not doing it anymore. So what you’re seeing is the first work I’ve ever really made where someone wasn’t pointing at what I should be photographing.

I would say you’re seeing my work for the first time at the age of 40. I’m choosing a subject and I’m photographing it until I feel like I’ve exhausted it. And hopefully there will likely be an exhibition and a book at some point in the future.

The work you’re seeing is me photographing my village. I’m photographing

the hills that are five minutes outside town and some of these abandoned buildings and the gauchos and their lifestyle.

It’s a revelation to hear you say this, and I’m jealous because I kind of feel the same.

You got there a decade before me, though. I feel like I’m doing the best work of my life only now, and it took untethering from what was so safe and familiar to finally find my own creative voice, to feel good about the things that are coming through me.

WH:

You’ve got to find your form. We all have to find our form to live.

MM:

So I’m heartened to hear you say that. I can’t wait to see what you’re putting in the can [read: film canister], as they say.

You have three guitars on the wall behind you. Which one’s your favorite? I mean, they’re all like children though, right?

WH:

The one on the bottom here, I built it. It was during this period of my life where I was like, what am I doing? And really, I was taking photographs for brands that should, honestly, all go to hell. I felt like I was just made of zeros and ones, just shooting digital work, and I wanted to make something real. So I took a class and made that guitar. It’s all hand built. And now my work is all film. I shoot nothing digital anymore.

MM:

Are you shooting Canon, Nikon, Fuji, a little bit of both?

WH:

I shoot with all mechanical cameras. I don’t shoot with any cameras that have a battery-operated shutter. So I’m shooting 35-millimeter.

This is a cheap Leica. It’s called a Leica R6, and it’s the last SLR that Leica made that doesn’t operate electronically. And then I shoot with a large-format 8x10 viewfinder where I literally am going under a curtain. It’s a big fucking piece of film, you know?

And so the juxtaposition between that really slow, thoughtful work and then that really fast, gritty work comes back to my work with you, Marshall, where it’s like, let’s do a beautiful portrait, but then let’s put the model spinning her dress or let’s shoot a portrait of the blues singer. But then I want a gritty picture of the bar.

That juxtaposition I learned in magazine work. And now I’m bringing that to my personal work. So it’s gritty but with really thoughtful stuff.

MM:

What’s the film you’re throwing in the camera?

WH:

When shooting large format, I’m using Ilford HP5 Plus 400. Large-format film is a very even-toned film, and HP5 Plus has great contrast, but then I want the opposite with the 35-millimeter. I want gritty stuff as well.

So I shoot the classic Kodak Tri-X 400. That’s what Sebastiano Delgado shot with. If it’s good enough for him, it’s good enough for me.

MM:

Are you processing it yourself, or are you sending it off?

WH:

I process it all here, in the yard. And I’m working on building my first dark room.

MM:

I have to say, I think it’s a genius move that you would put together such a beautifully rich, analog life. You’ve gone through the last decade and a half, two decades, sort of finding your way, mastering your craft. And now you’re coming into this full-circle moment where you’re educating others about what you’ve learned and how they can be good at their craft, all while falling in love.

And I dig that you’re putting in a dark room of your own. I love that you have this place that’s all very experiential. That you’ve arrived there with an open heart and your hands and a willingness to work.

WH:

I want to live in textures, you know, and I don’t want to live in the flat, in the digital.

What I appreciate about the analog processes is that they … they create texture, you’re recording a piece of history. Whether it’s the paint, a brushstroke. Or if you’re working with metal, the clink from a hammer. Or if it’s a photographic negative, the way the light has been recorded onto the plane. It’s not AI. There’s no artifice. There is only art from now on. Art made of hand, from soul and with heart.