SOUTH CAROLINA | GREEN POND

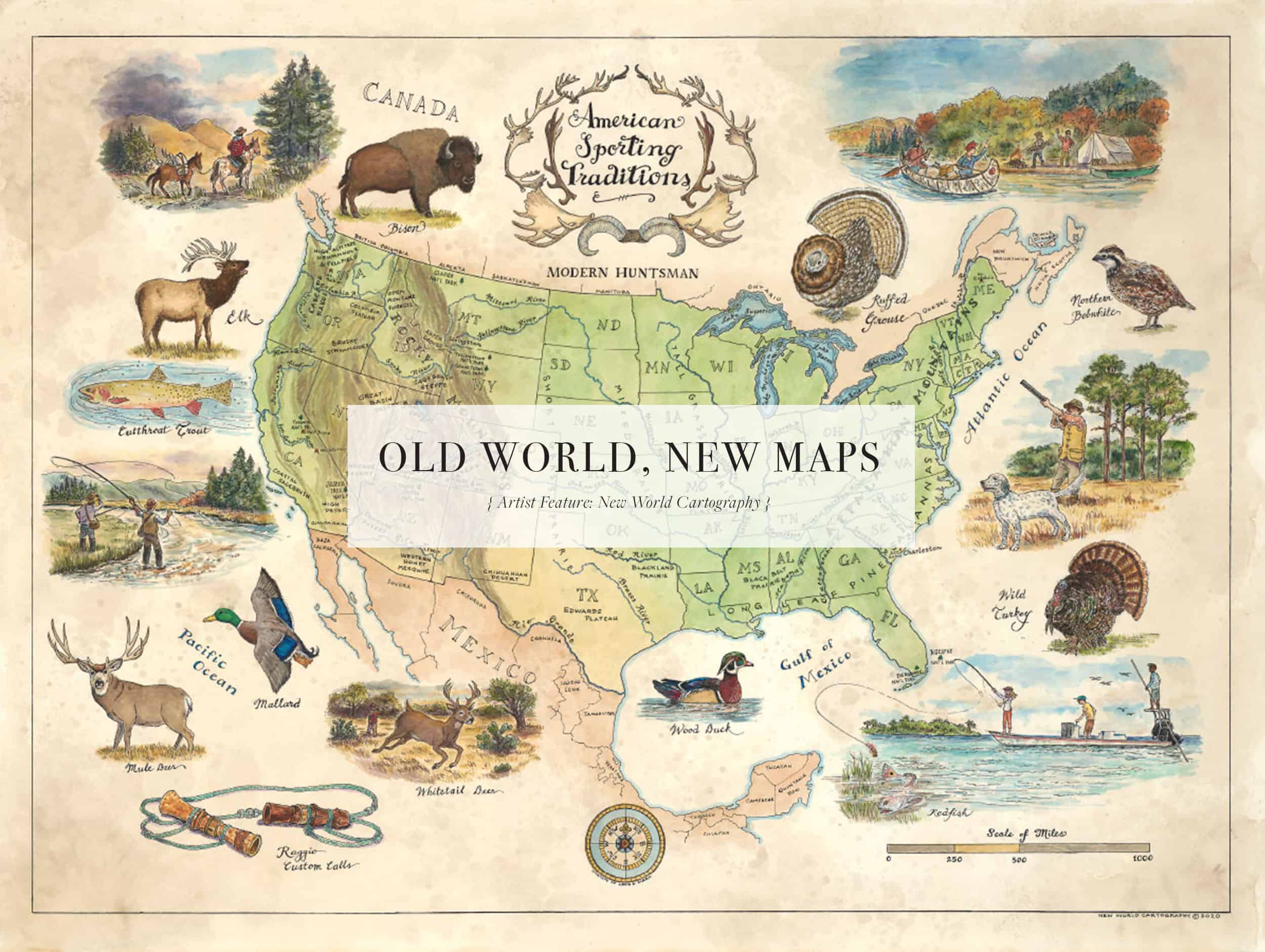

A map unfurls and fingers trace the leading lines of where we’re going and where we’ve been. Whether the year is 1784 or 2020, an aerial view of land and sea allows us to navigate environmental intricacies.

Formed in the lowcountry of South Carolina, New World Cartography resides where the past and present meet. For centuries, explorers have charted their course into unknown territory by the maps that would deliver them home again. Today, two men continue the tradition of hand-drawn maps, crafting 21st-century landscapes inspired by the antique maps of old.

For founder and designer Travis Folk, maps were an essential tool in obtaining his Ph.D. in wildlife biology and continuing his conservation work at Folk Land Management. As his fascination with maps grew, so did his desire to translate the sterile presentation of the information he was gleaning into a medium that was robust with life.

He partnered with classically trained artist Tony Waters in 2015, and they now work together in the age-old craft of producing accurate, informative maps with captivating original drawings depicting the unique flora and fauna of the topography.

Tony entertains a life-long enchantment with the history and allure of pirates and treasure maps to be found along his coastal home of Charleston, South Carolina. Each modern map conveys the same enchantment, his handiwork noted in the skill of hand-drawn lines and text, showcasing the brilliance of hand-applied coloration.

“It’s somewhat like the monks and their illuminated manuscripts,” said Tony. “The words are there, but the calligraphy and illustrations draw interest and attention.”

Reviving the tradition and process of originally designed maps, each commissioned piece is drawn, printed and then colored by hand — adding to the distinctiveness of each piece. Coloration techniques vary from watercolors to colored pencils