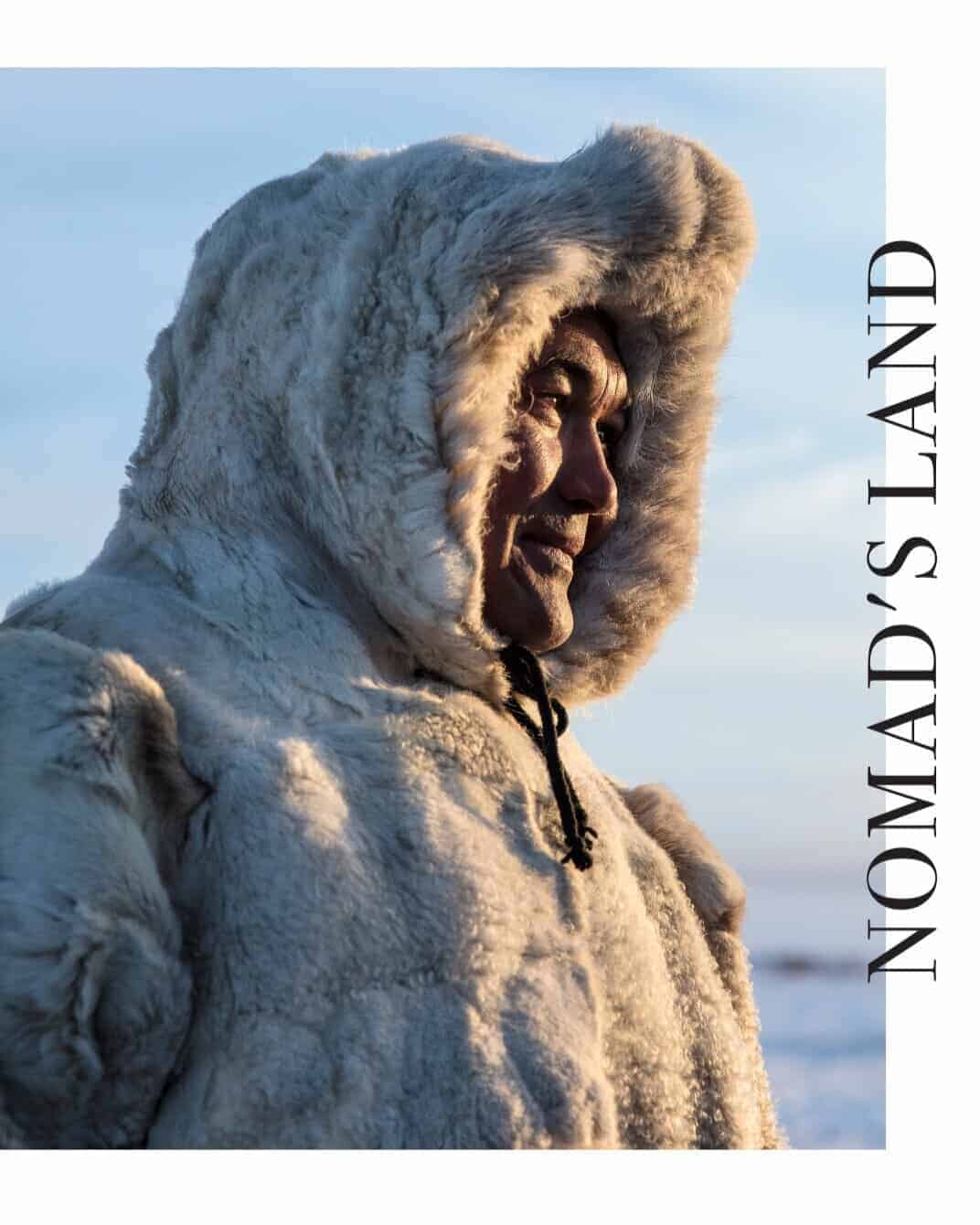

SIBERIA | 70.6598° N, 69.9045° E

Smoke rises in twisted cords from a row of tepees on a snowy knoll. At the clatter of our approaching snowmobiles, several women wound in thick furs emerge into the last indigo smolder of the Arctic evening. When we stop and alight, they whisper to one another in a language I’ve never heard. Children flitter in the shadows and point to us as if we’re ghosts.

In winter it’s always cold and dark,” said Sahsa, the moon-faced nenets, who was transporting us. “If we waited for light and warmth, we’d be three months behind the reindeer.

The Nenets, a tribe of nomadic reindeer herders who migrate seasonally across the Siberian tundra, have been living in this icy wilderness of northwest Russia for at least a millennium. Yet I’m here with only the second group of Westerners to ever visit this band of six families. Officially known as Brigade 20 — a relic of Soviet-era collectivization — this group travels some 600 miles down the Yamal Peninsula and back each year in the constant pursuit of forage for its animals. We’ve caught up with them near their southernmost range, but before the spring melt they must traverse the frozen waters of the Gulf of Ob, a 30-mile-wide ice sheet that separates their winter and summer grounds. Our goal is to make the crossing with them.

Siberia in winter might seem as appealing as, say, Death Valley in summer or Antarctica, well, anytime. Places of such climatic and geographic extremes are usually the realm of explorers, scientists, exiled dissidents, and native peoples who are shrewd and hardy enough to inhabit them. But the emptiness of the Siberian tundra, remote and removed from the comforts and distractions of modern life, is exactly what drew me. In the same way that I walk into the woods during hunting season to press pause on the constancy of our always-on world, I hope that winter in Siberia, one of the planet’s wildest and most sparsely populated expanses, will provide a backcountry escape